An interview with two of Project 51's co-founders, John Arroyo and Catherine Gudis, on the collective's recent "Play the LA River" card deck, a playable guide which invites participants to discover 56 unique sights along the entire Los Angeles River.

An interview with two of Project 51's co-founders, John Arroyo and Catherine Gudis, on the collective's recent "Play the LA River" card deck, a playable guide which invites participants to discover 56 unique sights along the entire Los Angeles River.

Planetizen: How was Project 51 formed and how did the group create the Play the LA River card deck?

Catherine Gudis: The founding of Project 51 came after Jenny Price, John Arroyo, and I led tours of the LA River as part of an LA Urban Rangers program in 2011. Jenny, a founder of the LA Urban Rangers, had been writing about and giving tours of the river for over a decade. John had written his thesis on the role of art in re-imagining the river as civic space, and I’d been exploring through public projects how art and history can reconnect people and place. When the three of us got together, we knew we wanted to craft a project that would engage people along all 51 miles of the river, through finding it, and seeing it as public space—as a place of possibility and connectivity, both for the longstanding residents of riverside communities and beyond. Since we all favor site-based artworks that are smart, funny, sometimes quirky, always steeped in research, and never ever earnest, we had some ground rules to get us going. Project 51 expanded organically to include a range of eight other artists and scholars—from performance and visual artists to a landscape designer to citizen scientists to public humanities practitioners.

John Arroyo: The group was interested in doing something that wasn’t ephemeral such as a single event or tour. Something playful, unique, and tangible—and not necessarily connected to a specific policy or plan. Personally, I was drawn to Jenny’s invite to join the group because it was nascent in its formation and did not have a specific project in mind. All we knew is that we wanted to build on the increasing awareness of the future of the LA River. We felt we could do that by helping people access the river now, not 20 years from now.

Where did the idea for the cards come from?

John Arroyo: A few years ago a friend of mine designed playing cards to highlight public spaces in Barcelona. Having witnessed the deck in action first hand, I liked how the cards doubled as both playing cards and as a local guide that could be used out of order.

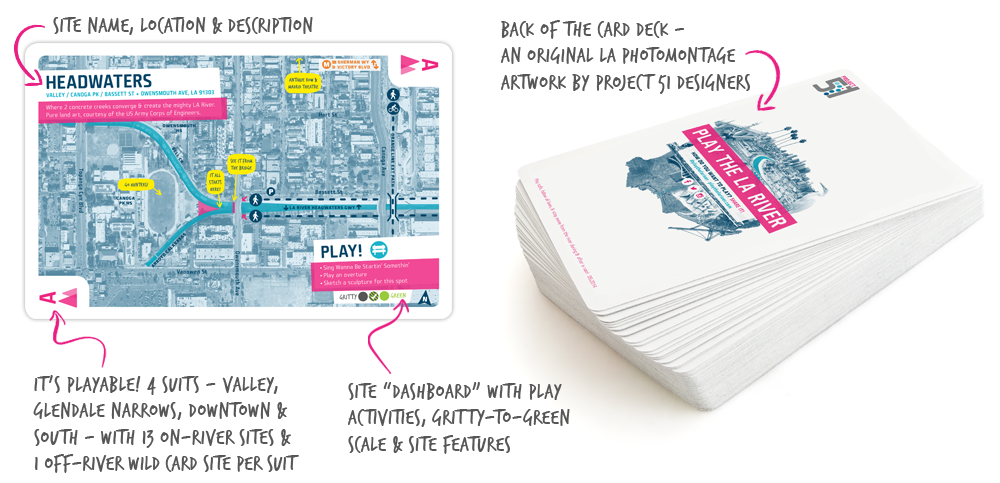

In the case of Play the LA River we focused on playing off two numbers: 51 and 52. The length of the river is 51 miles, historically, but when the Army Corps of Engineers concretized the river, it added an extra mile making it 52 miles. As we thought about the numbers, we realized there are 52 cards in a deck, 4 suits in a deck, and generally 4 main regions in the river (Valley, Glendale Narrows, Downtown, and South). The more we thought about the number 52, the more we made connections (such as 52 weeks in a year). But, instead of calling our group Project 52, we decided to stay loyal to the river’s original 51 miles and named the group Project 51. We also appreciated the opportunity to explain the discrepancy between 51 and 52 miles, especially in light of the momentum surrounding LA River revitalization efforts.

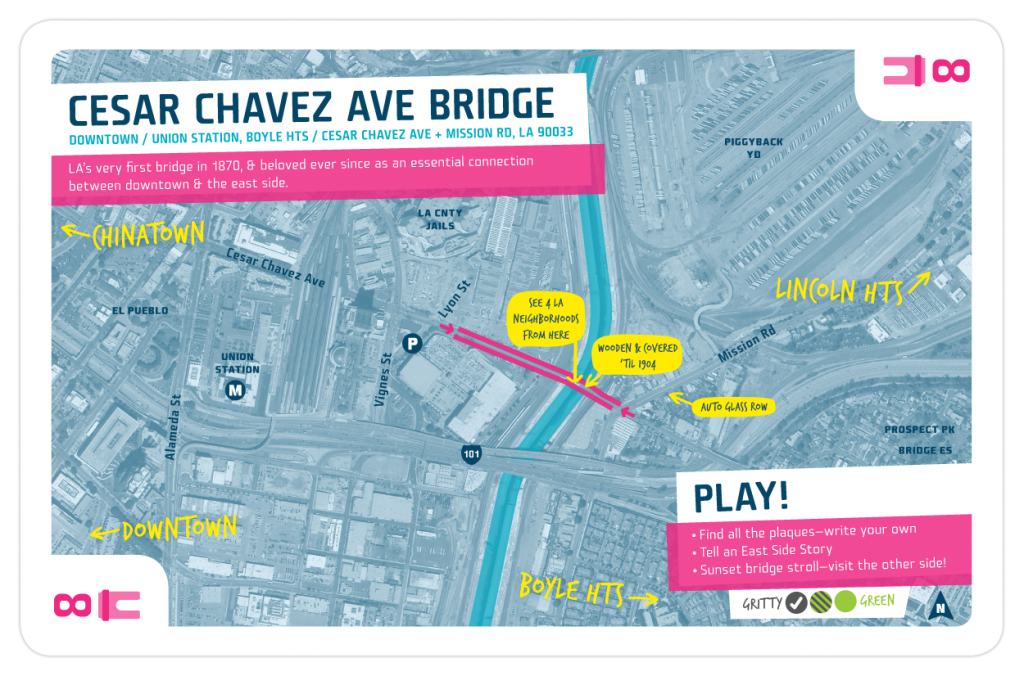

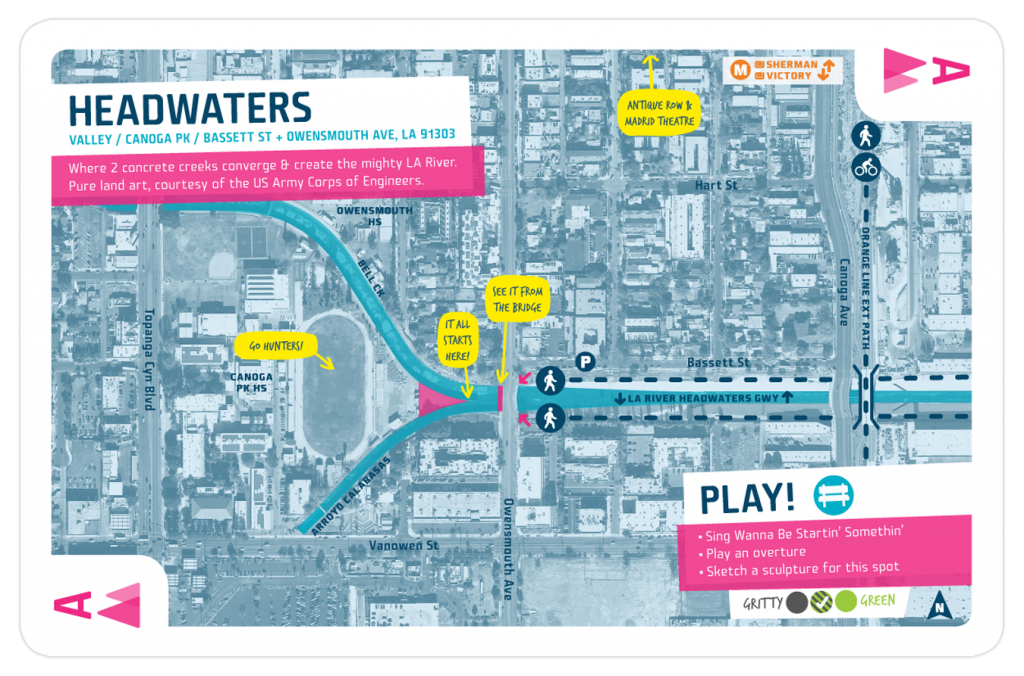

We didn't want do a traditional book-format guide, but rather a card deck that would serve a dual purpose: a playable deck and a guide to the river. Each card would highlight one representative site for each of the river’s 52 miles. We also wanted 4 wild cards (one for each suit), making the deck a total of 56 cards.

Catherine Gudis: We've been thinking about how play can be instrumental in one’s experiences of place, and how it operates on different levels—as an act of imagination, embodiment, strategy, critique. And fun, straight-up fun, which can get you pretty far. Play a silly game in an unlikely public place using whatever features of the site you see and find—and you’ve acted out the high-falutin’ theories of gaming, phenomenology, interventionism, third space. And you probably won’t forget that place—it becomes yours in a totally non-commercialized, non-privatizing way that’s also not dependent upon formal structures or an infusion of cash. It’s way more spontaneous. So, first and foremost we wanted to issue an invitation to play—all along the 51 miles, where there are parks and aren’t, where the vista and site is post-industrial and where it’s bucolically river-like in the traditional ecological sense. The cards were aimed to issue every recipient an artistic license to play in their own way, as an act of civic re-imagination of the river.

So the cards were about not being didactic or polemical and instead use a wee bit of sarcasm and irony as we call out ecological features (i.e., oil tanks in the distance, a park formerly a Superfund site, flowing water from upstream reclamation plants) and offer play prompts to reinforce or extend them (i.e., race toy cars at a site adjacent to former auto plants). Needless to say, the call outs and play prompts vary from card to card, from one section or suit to the next. Yet all aim to be open ended, to urge other people to come up with their own play, and then #playthelariver to tell the rest of us about it. We had unbelievably long conversations within Project 51 to put categories of play together, including food, dance, board games, songs, sports, and to make them relevant to the sites themselves.

How were the activities brainstormed? What's included in the cards?

John Arroyo: First we created a long list of potential sites, which we reduced to 52 sites with four wild cards. Next we scouted each site to check on site conditions, safety, access to transportation, parking, and public amenities. We checked our facts—especially in sites that were currently undergoing transformation and revitalization—with different local policy makers, planners, and advocates across LA County. Over the course of our project several sites were in constant flux. We needed to ensure that the details we collected were accurate before we committed information to a card.

Catherine Gudis: They do pack a wallop though. For example, one of the cards, Sunnynook to Yoga Park, makes reference to LA municipal ordinance 41.22, which prohibits loitering or resting. The signs for LAMC Sec 41.22 are all over the place, and simply ridiculous in their verbiage—you can’t rest, loiter, or lay down your bedding or a quilt. So we suggest the signs as a place to host a quilting bee, to point to how these kinds of ordinances have made for inhospitable public spaces. The river is a place for respite and rest, everyone ought to have the right to loiter and throw down a quilt, and river revitalization shouldn’t become yet more municipal code that makes poverty and homelessness itself illegal, but rather should address greater needs.

With such a large-scale volunteer-driven project, after you printed the cards, what was your public outreach strategy to get the word out about this awesome project?

John Arroyo: One of the main things we wanted to do was partner with different central river organizations and have them serve as distribution centers for the decks throughout the city. So not just UCLA on the Westside, but also in the Northeast at the LA River Center and various points in between. We are also working with local schools and our partners are distributing them at community meetings.

Catherine Gudis: So far, we have had a threefold approach to public outreach. We're inviting people to the river that have not been there. In addition, we’re reaching out to those who have historically lived along and used the river—to give them voice, and to illustrate the full range of possibilities that can be drawn from these existing communities to the designers and people who are working on the river. We believe riverside neighbors and a broad range of Angelenos need to be a part of the revitalization process, and by inviting them to play the LA River, we’re also inviting their reclamation of this grand civic space. And thirdly, we go out to groups that have the biggest reverberations with audience impact, including neighborhood groups, schools, and other nonprofits (arts and cultural groups and beyond)—particularly youth.

So now that we are about 16 weeks into the yearlong project, what has been the public response? Have the cards successfully gotten people out to the river who otherwise wouldn't explore it?

John Arroyo: I think people are starting to explore parts of the river they never have before. My experience growing up in East LA was that if you knew the river at all, you knew the part nearest to where you lived. The idea of exploring other parts of the river, like Long Beach down South or the Sepulveda Basin in the San Fernando Valley, was foreign for many underserved river-adjacent communities burdened by poor access to adequate transportation options.

So the card deck gives people the opportunity to branch out of their own neighborhood and explore the entire rivershed, one mile at a time. While the City of LA has been busy with various river-related revitalization projects along their 32 miles, so have other cities downstream as well. That’s an additional 20 miles downstream, but unfortunately many people don’t realize those projects are occurring in tandem. It’s been great to hear that the cards are helping people see the river as a regional resource, rather than just an isolated neighborhood one.

Cathy Gudis: Two weeks ago we saw the results of some of the visionary multimedia river-related artworks from artworxLA, a program which pairs working artists with alternative high school students, some of whom might be called "at-risk" or who are from underserved neighborhoods. Students presented their amazing visions for the river, used its history to speak of their lives, engaged the metaphor of the river as a planning tool, used photography, fashion, and book art to envision the river as an accessible public space. For the most part these kids hadn’t been to the river, or to any river. So it was interesting to see the way that they got the idea of play in all its forms, and took those prompts of re-imagining the river in totally different directions.

What’s coming up for Play the LA River in the next couple of months?

Catherine Gudis: In mid December, we're hosting a zine-making workshop along the river. After the new year, we’ll be working with a group called Opera del’Espacio on participatory performance, and in spring we hope to host another LA Urban Rangers River Ramble downtown, somewhere along the 6th Street Bridge, and way more. Most of all, we’re calling on you—for one and all to pick a card, and play…and even invite the rest of us to come along!

Alabama: Trump Terminates Settlements for Black Communities Harmed By Raw Sewage

Trump deemed the landmark civil rights agreement “illegal DEI and environmental justice policy.”

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

The 120 Year Old Tiny Home Villages That Sheltered San Francisco’s Earthquake Refugees

More than a century ago, San Francisco mobilized to house thousands of residents displaced by the 1906 earthquake. Could their strategy offer a model for the present?

Opinion: California’s SB 79 Would Improve Housing Affordability and Transit Access

A proposed bill would legalize transit-oriented development statewide.

Record Temperatures Prompt Push for Environmental Justice Bills

Nevada legislators are proposing laws that would mandate heat mitigation measures to protect residents from the impacts of extreme heat.

Downtown Pittsburgh Set to Gain 1,300 New Housing Units

Pittsburgh’s office buildings, many of which date back to the early 20th century, are prime candidates for conversion to housing.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Clanton & Associates, Inc.

Jessamine County Fiscal Court

Institute for Housing and Urban Development Studies (IHS)

City of Grandview

Harvard GSD Executive Education

Toledo-Lucas County Plan Commissions

Salt Lake City

NYU Wagner Graduate School of Public Service