More than a century ago, San Francisco mobilized to house thousands of residents displaced by the 1906 earthquake. Could their strategy offer a model for the present?

Editor’s note: For years, all across the country, tiny home villages have been proposed as a solution to the homelessness crisis. From Los Angeles to Detroit, tiny homes have champions, critics and many who acknowledge that, while not a permanent fix, they are an essential rung on the ladder to secure housing — or at least one that’s here to stay.

But the tiny home solution is not as new as some might think. A powerful example lies nearly 120 years back in America’s history. Amidst San Francisco’s ambitious announcement to add 1500 shelter beds in just 6 months, architect Charles Bloszies suggests that the future of the city’s rapid shelter bed rollout might just lie in its past.

At 5:12am on Wednesday, April 18, 1906, a portion of the seam between the two tectonic plates San Francisco rests on suddenly ruptured. The earth shook for 45 seconds, and the ensuing fire raged on for four days. Half of the city was wiped out and over 20,000 people were left homeless.

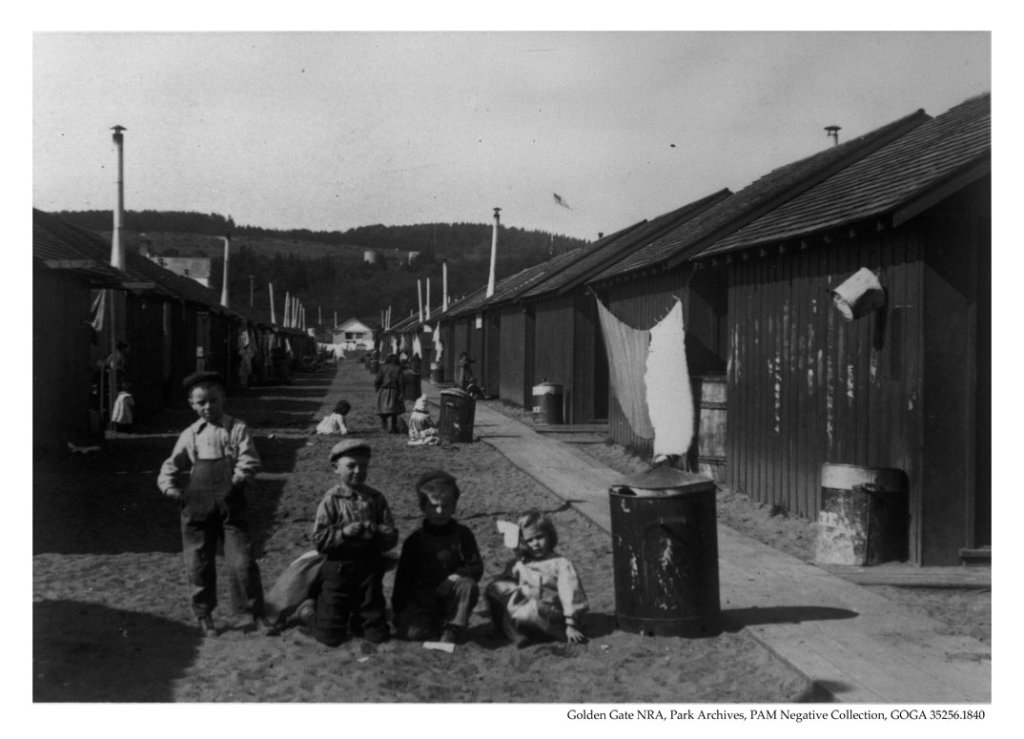

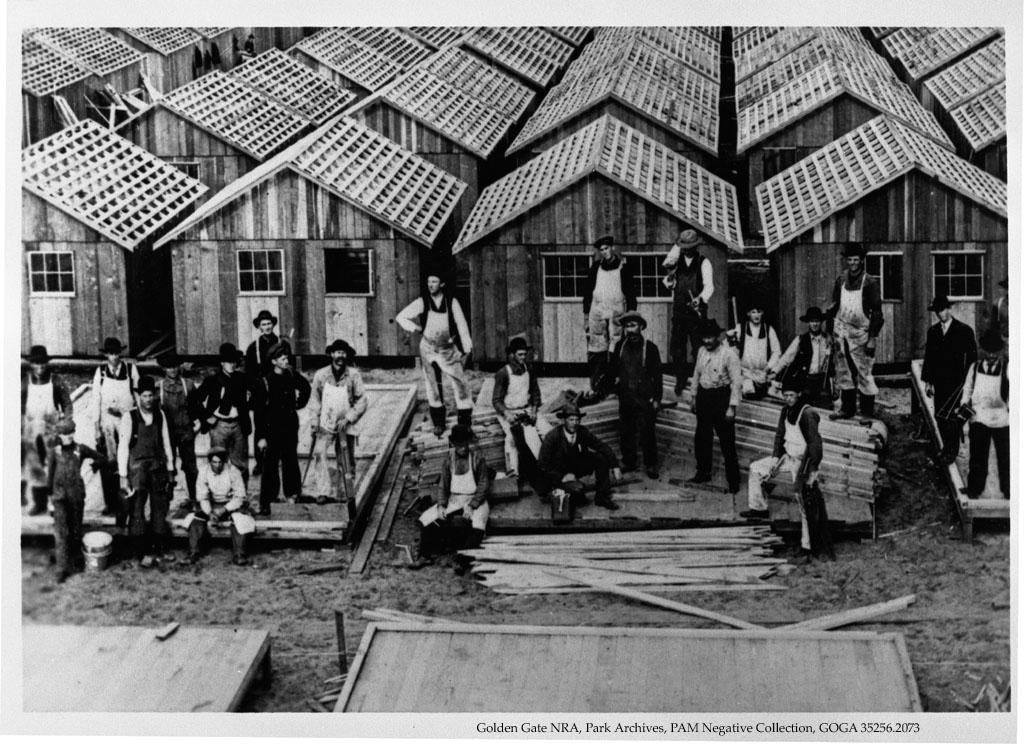

City leaders formed the San Francisco Relief Committee, which, aided by the U.S. Army, organized refugee camps and built 5,610 tiny, two- and three-room shelters to house those displaced by the earthquake and fire.

These endearing little structures were called Earthquake Cottages and they were rapidly deployed cheek-to-jowl on city parks and squares including today’s Moscone Park, Victoria Manalo Draves Park, Jefferson Square, Franklin Square, Hamilton Square, and many others. Displaced residents rented them for $2 a month, which could be applied to a purchase price of $50 — with the proviso that the owner would move their cottage to a permanent location.

The Earthquake Cottage footprint was about 150 square feet, wood framed with a cedar shingle roof. They had no bathroom, no kitchen, and no foundation (plumbing and related utilities were installed at each site to allow for the construction of communal bathroom, kitchen, and laundry facilities). Each individual cottage had a stove (for heat only) with a metal flue. Cottages were mass produced using construction techniques commonplace at the turn of the 19th century, and horse-drawn wagons moved them around. By some accounts the cottages ultimately housed nearly 17,000 residents.

Given the nostalgic feelings we might have of the Earthquake Cottage today, it is worth pointing out that there was a backlash a year after the earthquake and fire because not all the cottages had been relocated — some of the refugee camps remained. A sort of NIMBY movement formed, arguing that the city should remove the cottages and return the parks back to the public. As a result, some residents were evicted, and a number of cottages were torn down.

Ultimately, though, the initiative was a success. The City of San Francisco estimates that a substantial number of Earthquake Cottages were moved to permanent locations. A number of these cottages survived in the long term and have become historic landmarks. They have been modernized and expanded. Kitchens and bathrooms have been added. They are still lived in today, and are cherished by their residents. The San Francisco Chronicle even published an interactive map showing where a number of the remaining cottages stand in the greater San Francisco area; there is an especially dense cluster in the city’s Bernal Heights neighborhood.

Today’s shelter emergency took longer than 45 seconds of earth shaking to form, but the forces influencing a design solution are similar.

Our firm has become reacquainted with the Earthquake Cottage through longstanding planning and design work on interim housing solutions. In collaboration with public agencies and nonprofit service providers over the past decade, we have designed congregate shelters and campuses with hundreds of modular interim supportive housing units. Based on our experience, we believe that addressing today’s homelessness problem with small shelters like the Earthquake Cottages might be the most viable course of action.

Pre-manufactured, fully assembled, individual tiny units are easier to array on an irregular site, and in our experience, most sites available for housing the homeless are irregular. Although not nearly as dense as low-rise apartment buildings, an array of single-story tiny units do not need stairs and elevators. And, if designed with durability and sustainability in mind, units may be refurbished and relocated elsewhere.

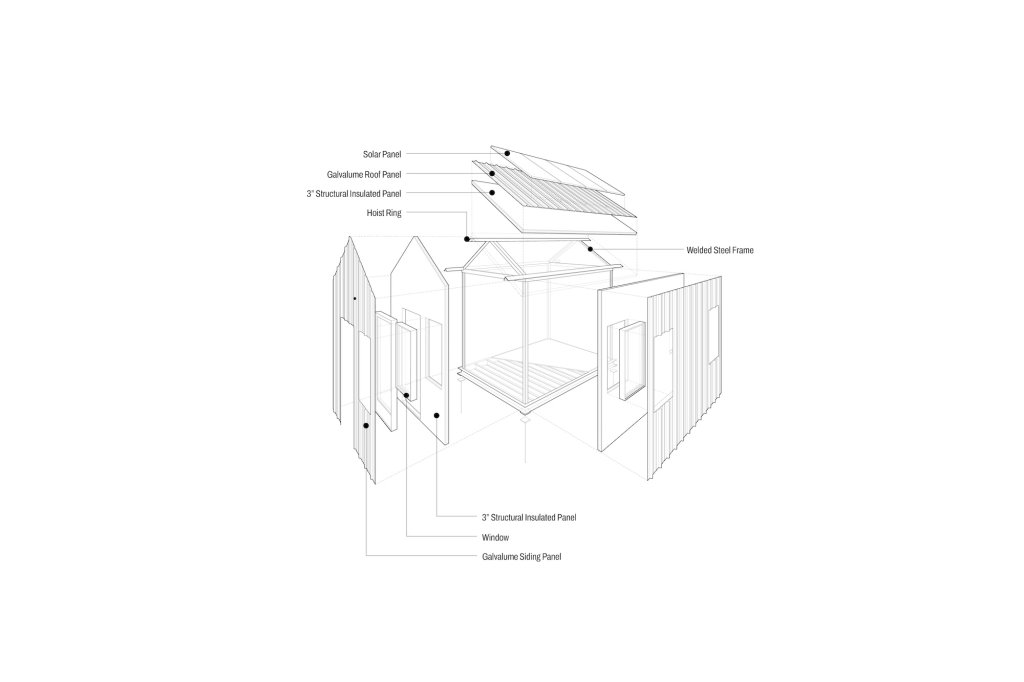

With these ideas in mind, we have designed a modern version of the Earthquake Cottage: we call it the NowHouse. Its footprint is a little over 100 square feet, steel framed with metal cladding. It has no bathroom and no kitchen — these are provided externally. Solar panels power lights and a small heater/AC unit, plus an outlet to charge a phone.

Built and furnished in a factory, the NowHouse can be transported by truck and moved around with a small, truck-mounted crane — a modern version of the horse-drawn wagon that transported the Earthquake Cottages. The NowHouse interior is durable and easy to clean, with enough space for a double bed, side table, desk/table, and a built-in counter with cabinets below (including a lockable drawer) plus a long shelf above. It is cozy, with enough space for singles or couples, and designed to accommodate wheelchair users. The Interior finishes have been chosen to be easily refurbished for a new occupant.

On the technical side, the NowHouse’s steel frame and cladding are fire-proof, as fire is a major concern in encampments. The frame is even equipped with lifting eyes so the structure can be picked up and moved without difficulty after its initial placement. The structure is so light that for most sites it does not need any special foundation except for stakes to hold it down to prevent it from blowing away (or jiggling away during the next earthquake!).

In some ways this approach accords with a broader cultural pivot towards ‘tiny homes’ as a solution for housing challenges. But it is important to recognize that the solution is more than just a leak-proof sleeping enclosure, and the ‘villages’ created by plopping these boxes down on a site are often just as challenged as the tent encampments they have displaced — not to mention less thoughtfully considered from the perspective of building a sense of community.

Based on our experience designing seven facilities conceived to tackle homelessness, we have learned that unhoused people want what many people already have: security and privacy in a clean, supportive community. Good design starts with understanding the problem and listening, and the NowHouse approach aims to address this core need for both security and community: NowHouses can be arrayed in almost any configuration, including side-by-side “duplexes” and front-to-back “fourplexes.” A thoughtful site plan can include open space for socializing and sharing a meal with a neighbor, and these structures can even be used as offices for administrative staff and case workers.

Like the Earthquake Cottage, the NowHouse also has a shape that says ‘home.’ It looks like a comfortable little house and not like an industrially fabricated garden shed. Its metal siding is available in many colors, mostly quiet ones following trauma-informed design precepts. Clients coming to a facility off the streets want a calming environment, one that does not include the visual stigma of an institution, an avant-garde architectural experiment, or an encampment. And, of course, the same NIMBY opinions seen in 1906 persist today. Good design matters for winning broad public support; leveraging the Earthquake Cottages’ image and nostalgic charm with a contemporary analog may satisfy the largest number of stakeholders.

A solution like the NowHouse is just one piece of the puzzle. After all, rehousing San Franciscans after 1906 also required building a substantial amount of new, permanent housing, which our city needs today as well. But the tiny house approach is ideal for certain circumstances, especially for a city like San Francisco where any substantial forward movement on housing the unhoused has often felt vanishingly rare. If a well-designed solution is deployed on a site with existing buildings already in place containing bathrooms and space for support offices and meals, an attractive shelter community can pop up almost overnight. San Francisco has many such candidate sites. Urban development sites awaiting planning approvals are also ideal candidates, in part because neighbors know the parcel will eventually be developed, helping avoid the NIMBY pushback that eventually met the Earthquake Cottages.

Small clusters of NowHouses with modest support buildings could retain the community bonds already established in the encampment cultures in San Francisco and beyond. People might actually want to live there for a few months or so, until they are ready to move into permanent housing. And the broader public might actually come to embrace these mini campuses.

The legacy of San Francisco’s historic Earthquake Cottages prove that impactful solutions really can be found when good design meets the urgent needs of its moment. We need to learn from this example, and we can use it as the basis for taking action now. Today’s need is too great for us to let the example of the Earthquake Cottages remain just a history lesson.

Charles F. Bloszies SE, FAIA is a San Francisco-based architect and structural engineer. His eponymous firm is a hybrid of architecture and engineering known for renovated, adapted, and modified old buildings as well as new modern, context-sensitive urban infill structures — and for work designing navigation centers and supportive interim housing facilities to address homelessness in Northern California. The firm’s website is archengine.com.

Alabama: Trump Terminates Settlements for Black Communities Harmed By Raw Sewage

Trump deemed the landmark civil rights agreement “illegal DEI and environmental justice policy.”

Study: Maui’s Plan to Convert Vacation Rentals to Long-Term Housing Could Cause Nearly $1 Billion Economic Loss

The plan would reduce visitor accommodation by 25% resulting in 1,900 jobs lost.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Wind Energy on the Rise Despite Federal Policy Reversal

The Trump administration is revoking federal support for renewable energy, but demand for new projects continues unabated.

Passengers Flock to Caltrain After Electrification

The new electric trains are running faster and more reliably, leading to strong ridership growth on the Bay Area rail system.

Texas Churches Rally Behind ‘Yes in God’s Back Yard’ Legislation

Religious leaders want the state to reduce zoning regulations to streamline leasing church-owned land to housing developers.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Caltrans

Smith Gee Studio

Institute for Housing and Urban Development Studies (IHS)

City of Grandview

Harvard GSD Executive Education

Toledo-Lucas County Plan Commissions

Salt Lake City

NYU Wagner Graduate School of Public Service