The new traffic safety paradigm recognizes exposure — total vehicle travel — as a risk factor, and therefore the additional casualties caused by planning decisions that induce more driving, and the safety benefits of VMT reductions.

A few days ago the ITE Journal published our article, “VMT as a Metric of Sustainability: Why and How to Implement Vehicle Travel Reduction Targets.”

Sustainable transportation planning strives to maximize transportation system efficiency. This involves changing from mobility-based to accessibility-based planning, which strives to minimize the amount of travel needed to access services and activities. To help guide this shift, some jurisdictions have established vehicle travel reduction targets and are replacing level-of-service (LOS) with vehicle miles of travel (VMT) performance indicators. This article describes why and how to make this shift. It summarizes the ITE report, Vehicle-Miles Traveled (VMT) as a Metric for Sustainability.

This relates to a recent debate on the ITE's website concerning Professor Wes Marshall's new book, Killed by a Traffic Engineer. That book generated many passionate responses, including criticisms by members who didn't read the book but were offended by its title.

Marshall's research, described in my recent column, “Planners' Complicity in Excessive Traffic Deaths,” highlights problems of traditional transportation engineering practices that favor speed over safety and automobile travel over other modes, which unintentionally increase crashes.

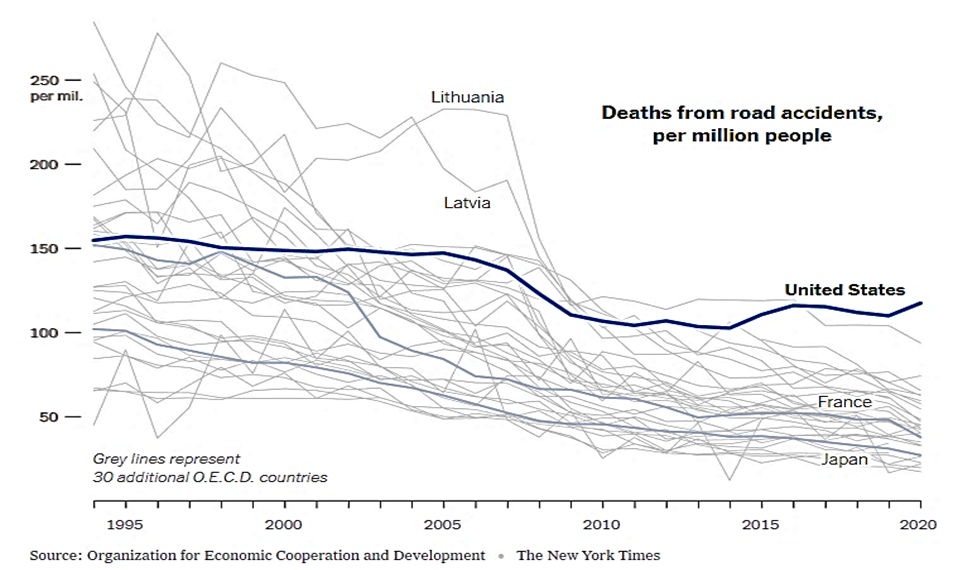

These relationships are illustrated in the following graphs. The first shows that, despite the best intentions of transportation practitioners and huge financial investments, the U.S. has a very poor safety profile compared with peer countries.

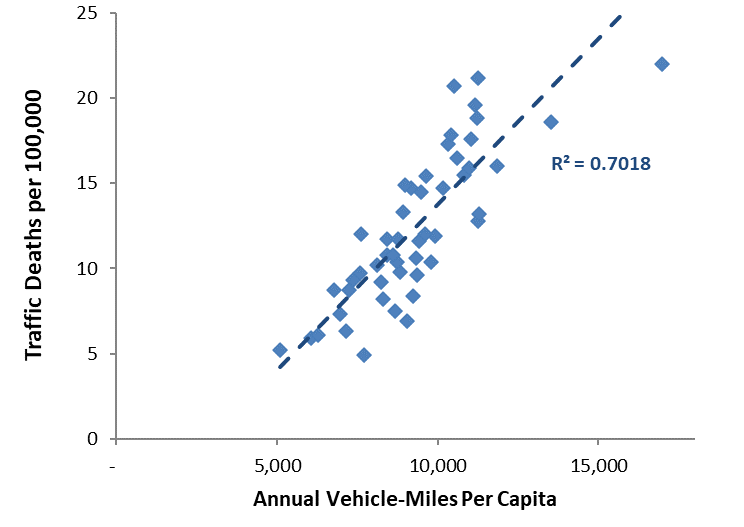

The second graph shows the very strong relationship between per capita VMT and traffic death rates, indicating that exposure -- per capita vehicle travel and traffic speeds -- is a critical risk factor.

The new traffic safety paradigm recognizes these relationships; all else being equal, planning decisions that increase traffic speeds and total vehicle travel tend to increase crashes, and decisions that reduce total vehicle travel (e.g., multimodal planning, efficient road and parking pricing, TDM programs, and Smart Growth development policies) tend to increase safety.

There are currently disconnects in the way planners analyze such strategies. VMT reductions are generally justified primarily to reduce traffic congestion or pollution emissions; safety impacts tend to be overlooked although they are often the most valuable benefit. Transportation models are starting to do a better job of reporting emission impacts but not safety impacts. To address this, traffic safety performance indicators should measure risk per capita, not per vehicle-mile/km, and modeling should report the expected changes in crash casualties caused by policies that change total VMT. My recent review of 24 traffic safety guidance documents indicates that most U.S. programs continue to use distance-based risk metrics and fail to consider TDM as a traffic safety strategy, as summarized below.

Review of Traffic Safety Programs

Program |

VMT Reduction Safety Strategies |

|

None |

|

|

Desktop Reference for Crash Reduction Factors, ITE (www.ite.org) |

None |

|

Developing Safety Plans for Rural Road Owners, FHWA (http://bit.ly/2px3hIA) |

None |

|

Getting to Zero Alcohol-impaired Driving Fatalities, National Academy Press (www.nap.edu/download/24951) |

Recommends improving public transit and ridehailing that serves alcohol drinkers |

|

Global Status Report on Road Safety, World Health Organization (http://bit.ly/1GsQ3DJ) |

Recommends walking, cycling and transit improvements. |

|

Integrating Road Safety into Existing Systems and Policy, Global Transport Knowledge Practice (www.gtkp.com/themepage.php&themepgid=376). |

Recommends integrated approaches, including multi-modal transport planning. |

|

Highway Safety Manual, AASHTO , (http://bit.ly/2oF4Xix) |

None |

|

None |

|

|

None |

|

|

Roadway Safety Guide, Road Safety Foundation (www.roadwaysafety.org) |

None |

|

Safe Ride Programs, Mothers Against Drunk Driving (www.madd.org) |

None |

|

None |

|

|

None |

|

|

Canada’s Road Safety Strategy (http://roadsafetystrategy.ca) |

None |

|

Toolbox for Road Safety (https://doi.org/10.1186/s40621-016-0098-z) |

None |

|

Traffic Safety Fundamentals Handbook, MDOT (https://bit.ly/48ESke3) |

None |

|

Transportation and Health Tool, USDOT and CDC (www.transportation.gov/transportation-health-tool) |

Recommends multi-modal planning for safety and health. |

|

Transportation Planner's Safety Desk Reference, USDOT (http://bit.ly/2oFbz0j) |

Recommends VMT reduction strategies. |

|

Vision, Strategies, Action: Guidelines (https://bit.ly/2ImGuum) |

None |

|

Vision Zero: Toolkit for Road Safety in the Modern Era (https://bit.ly/2VN2Blh) |

None |

|

Global Status Report on Road Safety 2023, World Health Organization (http://tinyurl.com/pxfupc) |

Recommends multimodal planning and traffic speed reductions for traffic safety. |

|

Enhancing Policy and Action for Safe Mobility, Sustainable Mobility for All (https://bit.ly/3XxWwXL) |

Recommends sustainable modes, compact development and vehicle travel reductions. |

|

World Report on Road Traffic Injury Prevention, Global Road Safety Partnership (www.grsproadsafety.org) |

Recommends demand management strategies. |

|

Zero Road Deaths and Serious Injuries: Leading a Paradigm Shift to a Safe System, (http://bit.ly/2nQZJmP) |

Recommends some vehicle travel reduction strategies. |

Of 24 major traffic safety programs reviewed, only eight mention multimodal planning or vehicle travel reduction strategies, and none provide detailed guidance on their evaluation or implementation.

This is unfortunate. The new paradigm expands the range of potential traffic safety strategies. For example, public transit improvements, parking policy reforms, and Smart Growth development policies can provide large crash reductions in addition to their other benefits. Comprehensive safety analysis can justify shifting resources from road and parking facility expansions to improving non-auto modes, implementing TDM programs, and creating more compact, walkable neighborhoods. Those investments become more cost-effective when we recognize their large safety benefits.

The old safety paradigm assumed that driving is generally very safe so it applied targetted safety strategies intended to reduce specific types of high-risk vehicle travel such as youth, senior and impaired drivers. Let me offer an illustrative example of how this may fail to increase safety.

In typical suburban areas many teenagers must travel to school by car. Since they are considered high risk, traffic safety experts support graduated license programs to reduce teenage driving. This forces parents to chauffeur children to school. Most chauffeuring trips involve empty backhauls so a five-mile trip by a teenage driver is replaced by a ten-mile round trip by parents. The old paradigm assumes that, since teenagers are high-risk and parents are low-risk drivers, this increases safety, and if measured using distance-based metrics (crashes per vehicle-mile), it is probably true, but if the teenager has twice the per-mile crash rate as the parent, there is no reduction in crashes per capita, and even if the parent is a perfect driver those additional vehicle-miles increase their risk of being the victim of another drivers’ error. This is why exposure is such an important factor – more vehicle-miles even by low-risk drivers increase overall crash risks.

The new traffic safety paradigm recognizes the additional risk resulting from increases in low-risk vehicle travel and so favors strategies that reduce total vehicle-miles such as improved public transit services with free service for students, efficient school parking pricing to discourage driving, and more compact communities that reduce distances between homes and schools. In addition to reducing traffic risk these strategies also reduce household costs, traffic congestion and pollution problems making them win-win solutions.

Below are ten specific ways that transportation agencies can apply the new traffic safety paradigm:

- Measure risk per capita rather than using distance-based metrics, which overlook the additional crashes caused by increased VMT and the safety benefits of vehicle travel reduction strategies.

- Shift from mobility-based to accessibility-based planning. This reduces the importance of speed and increases the importance on proximity, network connectivity and slower modes. Mobility-based planning tends to increase, and accessibility-based planning tends to reduce, crash risk exposure.

- Identify and correct planning biases that unintentionally favor speed over safety, automobile travel over other modes, and sprawl over compact development.

- Give more priority to pedestrian and bicycle safety, in recognition of the safety in numbers effect (total crash casualties tend to decline in a community as active mode shares increase).

- Support Smart Growth policies that create more compact, multimodal communities with less free parking. Such neighborhoods have 60-80% lower traffic casualty rates than automobile-dependent, sprawled areas (in addition to other benefits. One of the most effective traffic safety strategies is to ensure that any household that wants can find suitable housing in a compact, walkable neighborhood.

- Support vehicle travel reduction targets, policies, and programs, as described in our new article.

- Improve modeling to more accurately predict induced vehicle travel, and therefore the additional crashes caused by policies and projects that increase total vehicle-travel, and the potential safety benefits from VMT reduction policies and programs.

- Implement a more comprehensive analysis of the many economic, social, and environmental benefits of more multimodal and efficient transportation systems.

- Recognize that conventional traffic safety programs become more effective and politically acceptable with more accessible and multimodal transport planning. For example, graduated driver's licenses, special senior driver testing, and anti-impaired driving campaigns require that youths, senior, and drinkers have good alternatives to driving.

- Emphasize win-win traffic safety strategies. For example, favor the traffic safety strategies that also increase affordability, provide more independent mobility for non-drivers, reduce pollution emissions, and avoid those that increase consumer costs and create more automobile-dependent communities. Conversely, when evaluating potential transportation emission reduction strategies, favor those that reduce total vehicle travel and therefore total crashes.

What do you think? Are your agencies and practitioners ready to apply the new traffic safety paradigm? If not, what are the barriers?

Trump Administration Could Effectively End Housing Voucher Program

Federal officials are eyeing major cuts to the Section 8 program that helps millions of low-income households pay rent.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Ken Jennings Launches Transit Web Series

The Jeopardy champ wants you to ride public transit.

California Invests Additional $5M in Electric School Buses

The state wants to electrify all of its school bus fleets by 2035.

Austin Launches $2M Homelessness Prevention Fund

A new grant program from the city’s Homeless Strategy Office will fund rental assistance and supportive services.

Alabama School Forestry Initiative Brings Trees to Schoolyards

Trees can improve physical and mental health for students and commnity members.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Ada County Highway District

Clanton & Associates, Inc.

Jessamine County Fiscal Court

Institute for Housing and Urban Development Studies (IHS)

City of Grandview

Harvard GSD Executive Education

Toledo-Lucas County Plan Commissions

Salt Lake City

NYU Wagner Graduate School of Public Service