Some experts claim that remote work is the most effective way to reduce vehicle travel, but my research indicates that improving and encouraging walking, bicycling, and public transit can provide larger impacts and benefits.

Last week Steven Polzin posted a Planetizen column, Leveraging the Choice Not to Travel, which argues that:

- Walking, bicycling and public transit improvements provide small vehicle travel reductions.

- Transportation demand management (TDM) has been tried but largely failed to achieve significant benefits.

- Telework (telecommunications that substitutes for physical travel, allowing people to work, school and shop from home) has the greatest potential for reducing traffic problems.

I want to thank Dr. Polzin for raising this issue but respectfully disagree with his conclusions. I wholeheartedly agree that significant vehicle travel reductions are needed to achieve transportation equity and efficiency goals. However, my research indicates that walking, bicycling, and public transit can provide larger reductions and benefits, and telework actually provides smaller reductions and benefits than he suggests. Let’s examine the evidence.

Non-auto travel demands

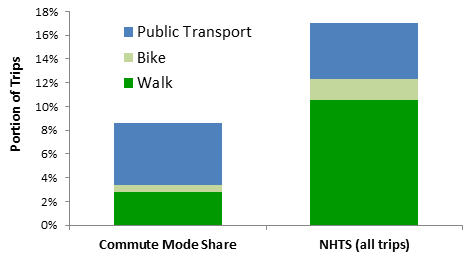

Conventional transportation planning tends to undercount and undervalue non-auto travel. For example, commonly cited travel data, such as Census journey to work statistics, ignore non-commute trips, school trips, recreational travel, and walk/bike segments of journeys that include motorized modes. A bike-transit-walking trip is categorized simply as a transit trip, and travel between parked vehicles and destinations are not counted even if they involve walking several blocks on public streets. Although non-auto modes serve only 8 percent of commute trips, they represent about 16 percent of total trips, indicating that people use these modes about twice as often as the most cited statistics indicate, and their mode shares could increase significantly if given more investment.

Non-Auto Mode Shares (U.S. Census, 2017 NHTS)

Ralph Buehler and Andrea Hamre’s study, The Multimodal Majority?, found that during a typical week 7 percent of Americans rely entirely on non-auto modes, about half use non-auto modes at least three times, and a quarter use a non-auto mode seven or more times.

TDM effectiveness

Polzin argues that transportation demand management policies—he cites commuter benefits programs, ride-matching services, plus education and marketing campaigns—have had little impact, but those are token strategies designed to allow transportation agencies to claim that they are making “balanced” investments without challenging current automobile-oriented planning practices. To be effective, a TDM program must include significant improvements in non-auto travel, financial incentives such as parking pricing or cash-out, Smart Growth development policies that allow more households to live in walkable urban neighborhoods, plus targeted travel reduction programs. The state of California's new Handbook for Analyzing Greenhouse Gas Emission Reductions and the Planner's Guide to Sustainable Urban Mobility Management can provide specific guidance for planning effective vehicle travel policies.

There is significant latent demand for non-auto travel. Surveys such as the National Association of Realtors’ Community and Transportation Preference Survey, indicate that many residents of automobile-dependent areas would prefer to live in more compact, walkable neighborhoods where they can drive less and rely more on non-auto modes. Non-auto travel tends to increase significantly after those modes are improved, as discussed in TDM Success Stories. For example, after Boulder, Colorado invested an extra $50 annually per capita in non-auto infrastructure their mode shares increased to about a third of all trips, and single occupant vehicle shares declined about 17 percent. The study, Don’t Underestimate Your Property, found that residential and commercial developments with TDM programs actually generate 63 percent fewer trips than trip generation models predict.

Polzin and others make a mistake when they assume a one-to-one substitution rate between modes. In fact, each additional mile of non-auto travel often reduces five to ten motor vehicle miles for the reasons described in the box below. These leverage effects are particularly large for mode shifts that result from auto travel disincentives such as efficient parking pricing, distance-based vehicle insurance pricing, and Smart Growth development policies.

Common Active Transportation Leverage Effects

|

In fact, even in affluent, automobile-oriented regions like California, automobile travel is much lower in compact, multimodal neighborhoods than in sprawled, automobile-dependent areas, as illustrated below. To reduce vehicle travel, communities need more compact infill development so any family that wants to can find suitable housing in a walkable neighborhood.

Household Vehicle Travel by Location (Salon 2014)

Current trends—aging population, urbanization, changing preferences, growing concerns about affordability, public health and environmental quality, plus improved telecommunications and e-bike technologies—are increasing non-auto travel demands and the value of serving them. You benefit if your neighbors drive less and use more resource-efficient modes. Walking and bicycling facility improvements can approximately double the portion of trips made by those modes, and e-bikes approximately double the portion of trips that can be made by bicycle. If bicycling currently has 2 percent mode share, this can increase to 4-8 percent if a community fully develops it bike network, as described in my column, Active and Micro Mobility Modes Can Provide Cost-Effective Emission Reductions–If We Let Them, and my TRB paper, Evaluating Active and Micro Mode Emission Reduction Potentials.

Completing a community’s sidewalk and bikeway networks typically costs an additional $50 to $100 annually per capita, which is tiny compared with what governments spend on roadways, businesses spend on off-street parking, and households spend on transportation, as discussed in my column, Completing Sidewalk Networks: Benefits and Costs. The problem is the low priority that transportation agencies currently give non-auto modes.

Currently, most North American communities devote less than 10 percent of their total transportation infrastructure budgets to non-motorized modes, which is less than indicators of their demands such as their shares of total trips, users, or traffic deaths, and far less than their potential shares if they received an equal share of investments.

Comparing Non-auto Infrastructure Investments with Demand Indicators (Litman 2023)

Telework benefits

Recent studies indicate that telework provides little or no net reduction in vehicle travel and associated costs. Working at home can reduce peak period trips but increases errand trips that would otherwise have been made while commuting, and some people use the option of working at home to move to more distant, sprawling locations where they must drive farther to access services and activities, as discussed in David Zipper’s column, “What if Working at Home Makes Us Drive More, Not Less?” Similarly, on-line shopping can reduce special trips to purchase a particular item, but not if items would be purchased during regular shopping trips, and it increases delivery vehicle-trips.

Telework can also exacerbate inequities. Although most middle-class homes have comfortable spaces for remote work, working at home can be difficult and inefficient for lower-income workers and students in crowded apartments.

To be comprehensive, telework analysis should account for:

Considering all of these factors, telework tends to provide modest or negative energy savings and emission reductions, unless implemented with vehicle travel reduction incentives. In other words, telework can be a useful option, but its overall impacts depend on how it is implemented. If you are a telework advocate, you should also advocate for vehicle travel reduction incentives to maximize net benefits. |

As a result, telework can only be assumed to reduce vehicle travel and associated costs if implemented with vehicle travel reduction and Smart Growth development policies. To maximize benefit, it should be implemented in conjunction with rather than instead of improvements to non-auto travel, Smart Growth development policies and TDM incentives. It should be optional, not mandatory.

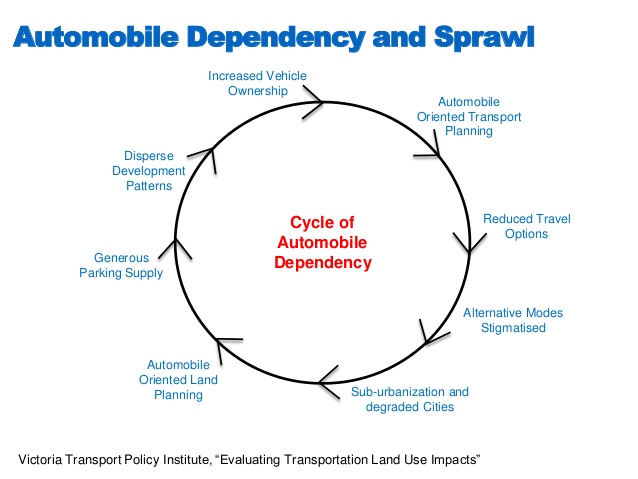

Don't dismiss modest modes

Too often, practitioners undercount and undervalue slower but more affordable, inclusive, and resource-efficient modes such as walking, bicycling, and public transit. This contributes to the self-reinforcing cycle of automobile dependency and sprawl, illustrated below. We have an opportunity to break this cycle by recognizing the unique and important roles that walking, bicycling, and public transit can play in an efficient and equitable transportation system, and the cost efficiency of vehicle travel reduction policies. Telework can help, but only if implemented as part of an integrated program to create a more diverse, efficient and equitable transportation system.

For More Information

Hannah Budnitz, Emmanouil Tranos and Lee Chapman (2020), “A Transition to Working from Home Won’t Slash Emissions Unless We Make Car-Free Lifestyles Viable,” The Conversation.

Nicholas Johnson, Dillon T. Fitch-Polse and Susan L. Handy (2023), “Impacts of E-Bike Ownership on Travel Behavior: Evidence from Three Northern California Rebate Programs,” Transport Policy.

Todd Litman (2023), Are Vehicle Travel Reduction Targets Justified?, World Conference for Transportation Research, Montreal.

Todd Litman and Meiyu (Melrose) Pan (2023), TDM Success Stories, Victoria Transport Policy Institute.

Todd Litman (2023), "Evaluating Active and Micro Mode Emission Reduction Potentials," Transportation Research Board Annual Meeting.

Duco de Vos, Evert Meijers, and Maarten van Ham (2018), “Working from Home and the Willingness to Accept a Longer Commute,” The Annals of Regional Science, Vo. 61, 375–398.

William O’Brien and Fereshteh Yazdani Aliabadi (2020), “Does Telecommuting Save Energy? A Critical Review of Quantitative Studies and Their Research Methods,” Energy and Buildings, Vol. 225.

Yao Shi, Steven Sorrell and Tim Foxon (2023), “The Impact of Teleworking on Domestic Energy Use and Carbon Emissions,” Energy and Buildings.

David Zipper (2021), “What if Working at Home Makes Us Drive More, Not Less?,” Slate.

Study: Maui’s Plan to Convert Vacation Rentals to Long-Term Housing Could Cause Nearly $1 Billion Economic Loss

The plan would reduce visitor accommodation by 25,% resulting in 1,900 jobs lost.

North Texas Transit Leaders Tout Benefits of TOD for Growing Region

At a summit focused on transit-oriented development, policymakers discussed how North Texas’ expanded light rail system can serve as a tool for economic growth.

Why Should We Subsidize Public Transportation?

Many public transit agencies face financial stress due to rising costs, declining fare revenue, and declining subsidies. Transit advocates must provide a strong business case for increasing public transit funding.

How to Make US Trains Faster

Changes to boarding platforms and a switch to electric trains could improve U.S. passenger rail service without the added cost of high-speed rail.

Columbia’s Revitalized ‘Loop’ Is a Hub for Local Entrepreneurs

A focus on small businesses is helping a commercial corridor in Columbia, Missouri thrive.

Invasive Insect Threatens Minnesota’s Ash Forests

The Emerald Ash Borer is a rapidly spreading invasive pest threatening Minnesota’s ash trees, and homeowners are encouraged to plant diverse replacement species, avoid moving ash firewood, and monitor for signs of infestation.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

City of Santa Clarita

Ascent Environmental

Institute for Housing and Urban Development Studies (IHS)

City of Grandview

Harvard GSD Executive Education

Toledo-Lucas County Plan Commissions

Salt Lake City

NYU Wagner Graduate School of Public Service