A simple explanation of why strict rent control reduces housing supply, and why moderate rent control does so to a much lesser extent.

Economists oppose rent control almost as unanimously as climate scientists oppose attempts to deny the reality of client change. 93 percent of economists (including liberals like Paul Krugman) agree that ceilings on rents reduce the quantity and quality of housing. And economists' views seem borne out by experience: most major cities with rent control (such as New York and San Francisco) tend to have very high rents, indicating that rent control is perhaps not functioning as effectively as its creators had wished. And yet urban planners and citizen activists are much more closely divided. What do they not understand?

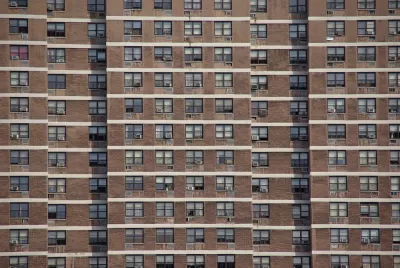

To understand the risks of rent control, imagine the strictest possible policy. Government freezes rents forever, prohibiting any landlord from increasing rents. As the costs of labor and utilities increase, landlords realize they are losing money by continuing to be landlords. So eventually landlords start to abandon property; if they cannot legally do so by converting apartments to condominiums, they do so illegally by letting property decay until a suspicious fire wipes out the landlords' problem. No new apartments replace these housing units, because no one will invest in housing if they can't make a profit by doing so. Eventually, renter-dominated areas turn into wastelands, like the South Bronx in the 1970s.

Of course, no city has ever enacted such a strict policy. A more plausible form of rent control treats landlords as public utilities: government could limit rent increases rather than freezing rents, by providing that a landlord could increase rents by only a certain amount this year (say, the costs of increased landlord expenses). In this scenario, landlords will not abandon property as rapidly as in the first scenario. Nevertheless, this policy will still cap housing supply; even if existing landlords are less likely to jump ship, new landlords will be unlikely to enter the market. Here's why: rental housing competes with other, non-regulated investments. That is to say: if I have money that I could invest in (a) a business where my profits were capped by government (e.g. rental housing in this scenario) or (b) a business where government wants people to make huge profits (e.g., the stock market, single-family housing), I would, other things being equal, crazy to invest in (a). In this scenario, rent control creates housing shortages, much as Soviet centralized planning created shortages of consumer goods.

Having said that, in reality rent control is not quite as toxic as in my hypothetical scenarios. In the United States, most cities with rent control do not regulate quite as intensively as in my hypotheticals; for example, in New York only older units are covered. Such "moderate rent control" does not reduce housing supply as much as would universal rent control, because it only caps rents in a limited slice of the market. On the other hand, this means that "moderate rent control" also doesn’t do much very much good—rents in New York are in fact sky-high for most people other than longtime residents. In other words, moderate rent control doesn't control rents very much. So what's the point?

Defenders of rent control point out that the correlation between rent control and housing supply is incomplete; for example, places that have removed rent control (such as Boston) have not always experienced construction booms, while highly regulated New York built lots of new housing in the 1950s. But this is to be expected from the above discussion of moderate rent control: if rent control is too weak to actually reduce rents, it is also going to be too weak to restrain supply as much as a policy that did reduce rents.

And where rent control is relatively weak, it is just one factor affecting the supply of new housing: for example, zoning laws generally treat apartments as an undesirable use, and thus may restrain housing supply far more aggressively than moderate rent control. Conversely, if government allows lots of new housing construction, new housing will be built as long as rent control is not so strict as to prevent it. Similarly, if government subsidizes new housing or builds new housing itself, the positive results of such construction may be more important than the effects of moderate rent control.

In sum, the difference between strict rent control and moderate rent control is like the difference between smoking two packs of cigarettes a day and smoking two cigarettes a day. Smoking two packs of cigarettes a day, like strict rent control, is likely to create toxic results. Smoking two cigarettes a day, like moderate rent control, is far less harmful though still not ideal.

Trump Administration Could Effectively End Housing Voucher Program

Federal officials are eyeing major cuts to the Section 8 program that helps millions of low-income households pay rent.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Ken Jennings Launches Transit Web Series

The Jeopardy champ wants you to ride public transit.

California Invests Additional $5M in Electric School Buses

The state wants to electrify all of its school bus fleets by 2035.

Austin Launches $2M Homelessness Prevention Fund

A new grant program from the city’s Homeless Strategy Office will fund rental assistance and supportive services.

Alabama School Forestry Initiative Brings Trees to Schoolyards

Trees can improve physical and mental health for students and commnity members.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Ada County Highway District

Clanton & Associates, Inc.

Jessamine County Fiscal Court

Institute for Housing and Urban Development Studies (IHS)

City of Grandview

Harvard GSD Executive Education

Toledo-Lucas County Plan Commissions

Salt Lake City

NYU Wagner Graduate School of Public Service