As cities provide incentives for density, it's important that new multi-family buildings implement best practices for natural ventilation to achieve quality of life and energy efficiency benefits.

Every year, more than one third of U.S. energy consumption goes to light, heat, and cool buildings. Energy costs are a burden to the individual as well as the nation. Mechanical cooling and ventilation relies on electricity; it takes three times the amount of a primary fuel like coal or natural gas to produce electricity.

Across cultures and through human history, people shaped their houses and placed their windows to shield themselves from unwanted sun and heavy winds while capturing cooling breezes. As architects, planners, and developers respond to public interest in sustainable buildings, natural ventilation is once again emerging as a critical component in multi-family buildings.

Across cultures and through human history, people shaped their houses and placed their windows to shield themselves from unwanted sun and heavy winds while capturing cooling breezes. As architects, planners, and developers respond to public interest in sustainable buildings, natural ventilation is once again emerging as a critical component in multi-family buildings.

As we discuss in our book, This House is Just Right: A Design Guide to Choosing a Home and Neighborhood, a comfortable home is designed to maintain natural lighting, good ventilation, and optimum temperature and humidity levels. When the weather is hot and humid outside, a sustainable home is open to breezes that cool and dry the skin. When it is cold outside, a sustainable home is warm, free of drafts, and circulates fresh air to avoid feeling stuffy.

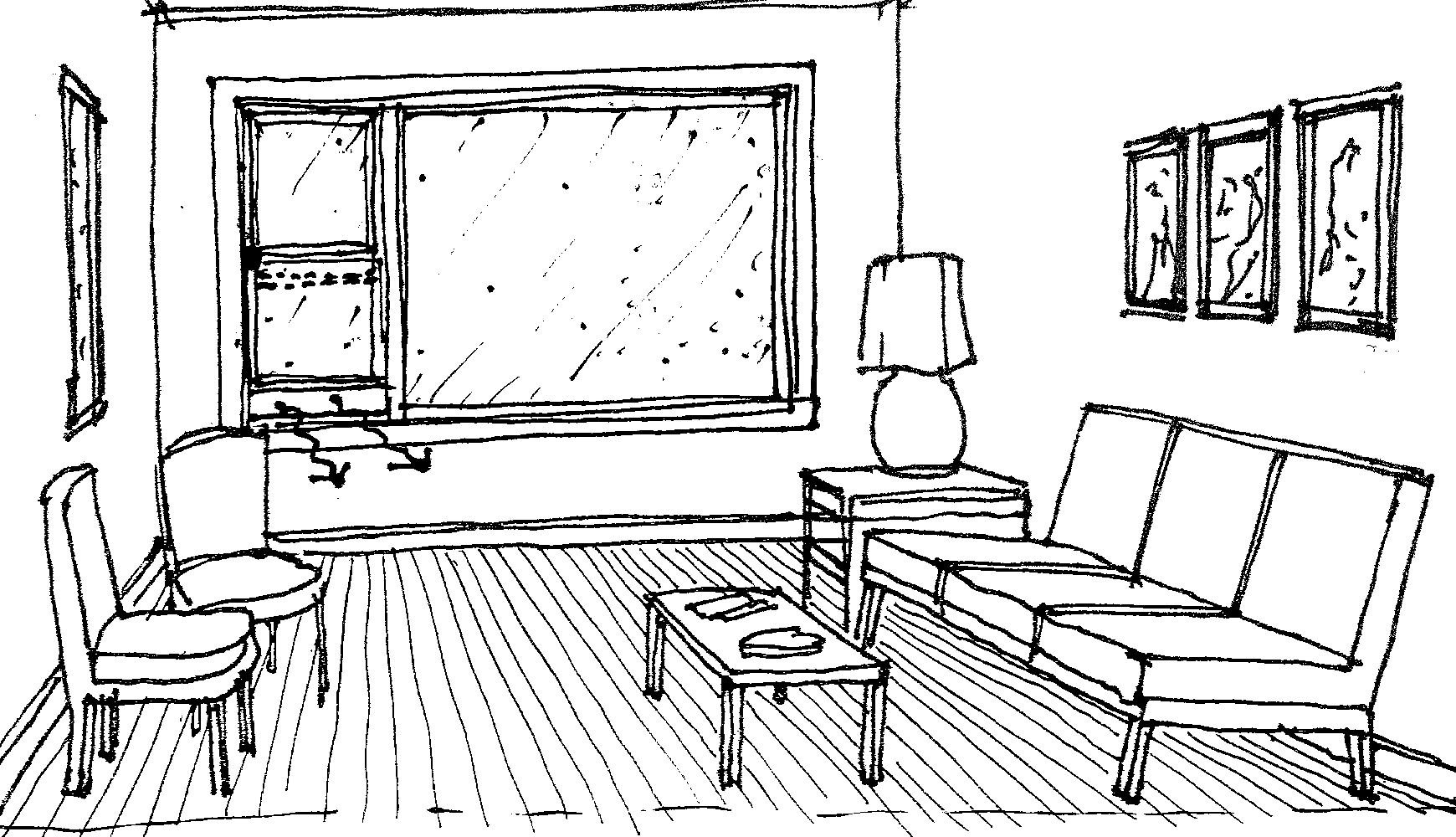

Many people prefer natural to mechanical ventilation because it is cheaper, easier to control, and it naturally connects the home with the outdoors. Mechanical ventilation can aggravate asthma and allergies because of condensation and mold in or on ducts. Air conditioning is expensive and many people do not like the feeling of being in a closed refrigerator. There can be a cold wetness to the air and an unpleasant, musty smell. With natural ventilation, windows are open to fresh air and to the sound of birds singing, breezes rustling through the leaves, kids playing. Maybe traffic, sirens, and car alarms as well, but that is another story.

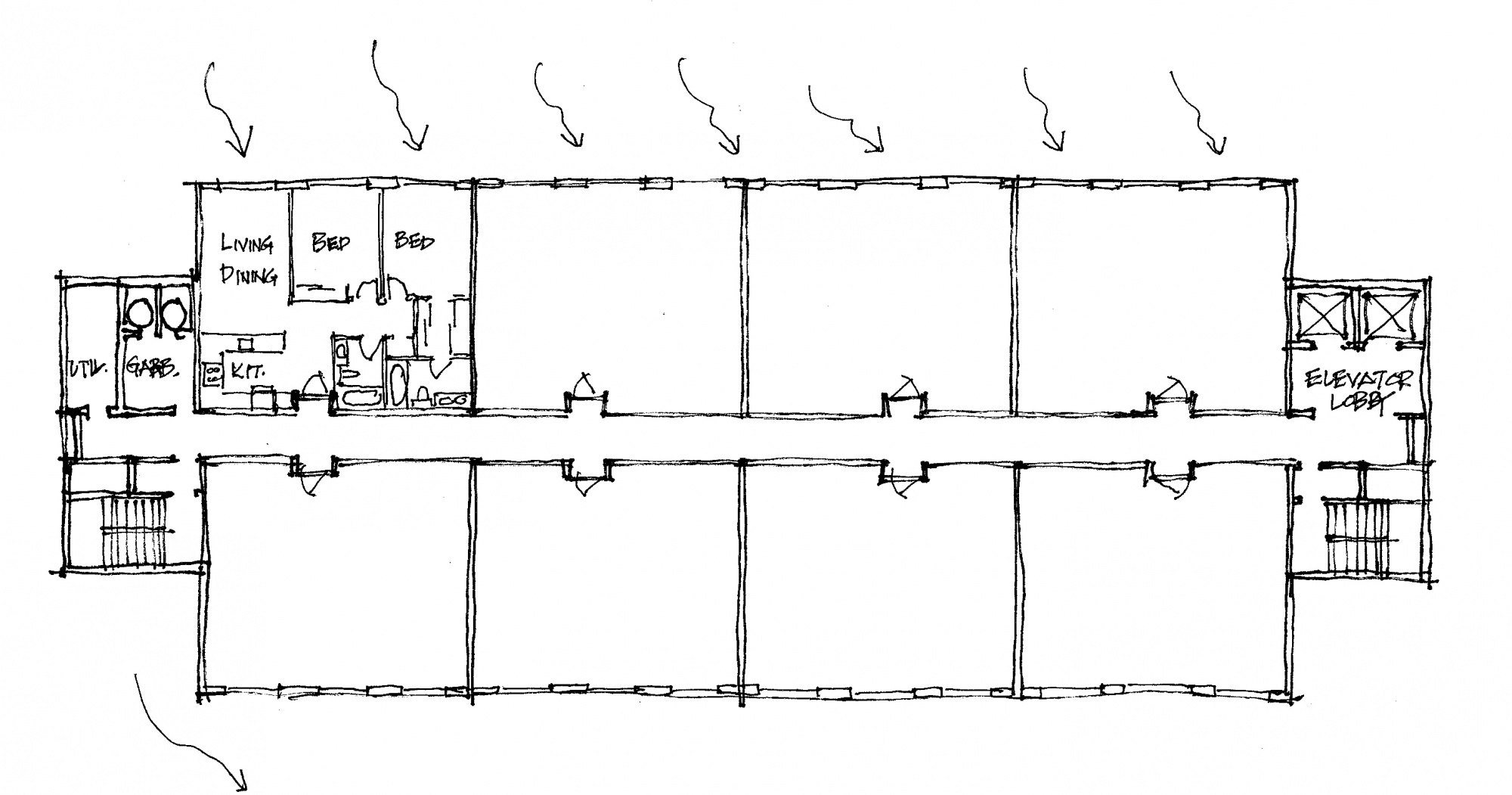

The number of windows, their placement in a room, and their location on the building exterior determine how often the air in a room is replaced by fresh air. By building code, every living and sleeping room of a dwelling unit must have at least one operable window. Detached houses with windows on all four sides and well chosen landscaping are best for natural ventilation. But, with average densities between four and ten dwelling units per acre, detached houses also use a lot of land, much of it devoted to cars. City living and efficient public transit require higher residential densities than are possible with detached houses. City neighborhoods with mid- and high-rise, stacked flats offer the greatest density [pdf], with between 35 and 125 dwelling units per acre, if just one car per unit is accommodated. The typical mid- and high-rise building is rectangular and has a double loaded corridor in the center. Elevator access is efficient; stairwells are at the ends of corridors per the building codes. With their flat facades and uniform rows of windows, most units have single orientations that do not invite fresh air.

An example of a double loaded corridor. (Image by R. Thomas Jones)

An example of the single orientation of rooms in high density buildings. (Image by R. Thomas Jones)

However, it is possible to design buildings that achieve desirable densities for city living and also invite fresh air into every room. Understanding how to bring wind into a building can make a big difference in how comfortable the building is to live, work, or plan in.

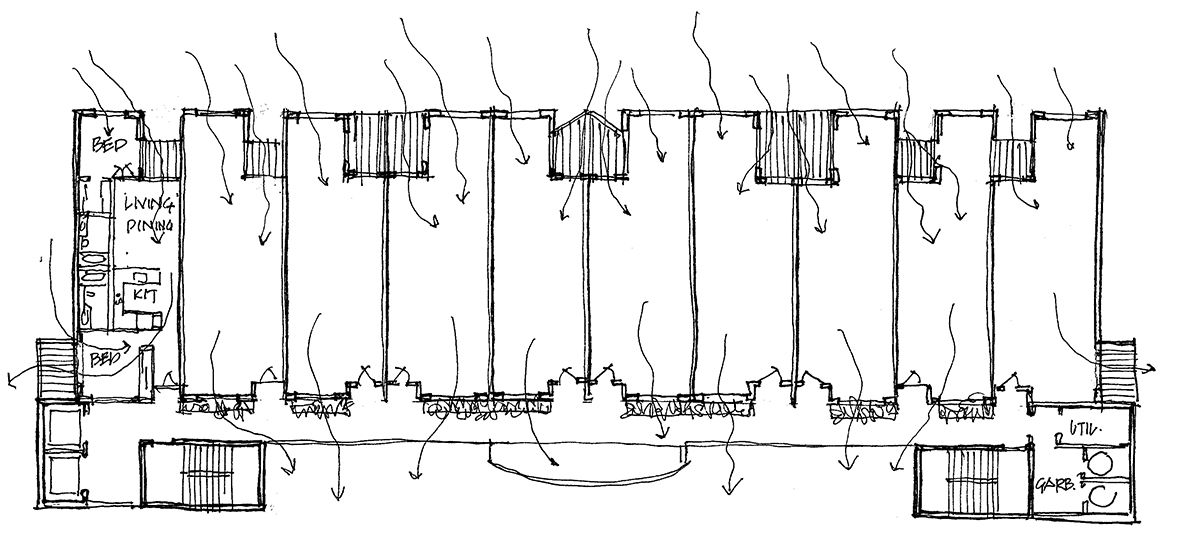

Large buildings deflect the wind; well distributed openings on both the lee and windward sides of a building benefit from the pressure of the wind to drive air through the windows. With cross ventilation, air enters one side and leaves on the opposite side, but the pressure can also cause single side and vertical ventilation flows.

Design strategies that take advantage of wind pressure and buoyancy for bringing fresh air into every unit of a multi-family building include the following: 1) placing windows both high and low in rooms without cross ventilation, 2) including projections and recesses that increase the number of exposures, and 3) building separate cores in the form of interior courtyards and air wells, single loaded corridors, and floor through apartments. There are examples of these strategies in the book, Good Neighbors: Affordable Family Housing, authored by Tom Jones, William Pettus, and Michael Pyatok.

Cascade Court Apartments in Seattle and Yorkshire Terrace in Los Angeles are examples of using simple building projections, like bay windows, and interior courtyards to increase the number of exposures and cross ventilate interior spaces. Cascade Court has bay windows, deep recesses in the building footprints, and jogs in the footprint. Yorkshire Terrace has a linear courtyard and deep recesses in the footprint.

If one set of windows is on a hot side of the building and another on a cool side, as shown in the above examples, the differences in air pressure will stimulate airflow. Projections and recesses in the building's exterior can create microclimates similarly stimulates air flow. Covered recesses that shade one side of a room, as shown in the drawing here provide a cool pocket of air, causing a difference in air pressure that stimulates air movement.

If one set of windows is on a hot side of the building and another on a cool side, as shown in the above examples, the differences in air pressure will stimulate airflow. Projections and recesses in the building's exterior can create microclimates similarly stimulates air flow. Covered recesses that shade one side of a room, as shown in the drawing here provide a cool pocket of air, causing a difference in air pressure that stimulates air movement.

In a typical multifamily building with a double loaded corridor oriented east-west, half the residents have a single orientation to the north. There is no direct sun; the homes are cold and dark and the heating bills are high. The other half who face south may have the opposite problem: excessive heat gain in the summer. By contrast single loaded corridors are a strategy for allowing air to move through a unit. The corridor is on one side of the building and open to the air. Each unit has windows on the corridor and windows on the opposite side of the building. Modernist architects often used these outside corridors that serve as sidewalks in the air. A single loaded corridor building along an east west axis will give a southern orientation and cross ventilation to all of the units. Architect George Keck’s Chicago Prairie Avenue Courts is an example. (Here is a link to Anthony Denzer's blog about subjects related to his book, The Solar House: Pioneering Sustainable Design.)

Charles-Édouard Jeanneret-Gris, whose nom d' artiste was Le Corbusier, used single loaded corridors and floor-through apartments to optimize solar orientation and cross ventilation. Le Corbusier, a Swiss-French architect and urban designer, considered how to make cities habitable despite the growth in scale and density caused by the industrial revolution. His goal was to create dwellings for the masses that provided sunlight and fresh air. Responding to the windowless warren of rooms in ramshackle buildings inhabited by the working class, he designed buildings with floor-through apartments using a skip-stop corridor scheme. Corridors giving access to individual units occur every two or three floors. The elevator skips the floors without corridors; the individual units have internal stairs that connect to corridor floors. We must acknowledge that for reasons other than smart ventilation strategies some of Le Corbusier’s estates have been considered as non-replicable models.

Le Corbusier’s Unite d' Habitation in Marseilles, France is an example of spatially organizing units so that they span one side of the building to the other side. Double height living spaces reduce the required number of corridors to one every three floors. The end of each unit has windows, allowing for cross ventilation throughout the unit flowing through the narrow bedrooms into the double height space.

Habitable rooms need a continual supply of well-oxygenated air. In earlier times of low energy costs, buildings were not constructed so tightly as to preclude leaks from supplying some of the needed air. Current building codes are based on mechanically ventilating well-insulated and tightly constructed buildings. City developers are taking advantage of precious infill opportunities for deeper buildings with rooms ever further from exterior walls.

The methods for getting air deeper into these buildings include separate cores that are open to the sky for each group of apartments and projections that place rooms closer to or farther from the façade, such as bay windows and covered balcony recesses, open corridors, and floor through units. Why are these strategies not more widely pursued? Building codes stand in the way because they are designed to protect life rather than to enhance the quality and comfort of the interior rooms. Also, it costs more to depart from the usual rectangular building with a double loaded corridor and the typical flat facade with uniform rows of windows.

Designing a multi-family building to allow residents options for naturally ventilating their homes makes environmental, economic, and human comfort sense. American home energy costs average almost $2,000 a year per household. Residential use of electricity is growing because of increased use of technological devices and air conditioning. Each year in the U.S., air conditioning uses about 5 percent of the electricity produced, releasing about 100 million tons of carbon dioxide into the air. This is about two tons for each home with an air conditioner. At present, building codes do not require natural ventilation. "The IMC 401.3 (International Mechanical Code) does not say, 'The capability to control ventilation shall be provided...' or 'The occupants shall have the opportunity to control ventilation...'" Cities can add this to land use regulations and may do so in the future. In San Francisco, CA this issue is before the courts. A condominium owners association is suing architects of a 595-unit building, accusing them of creating a design that causes overheating. Homeowners allege that the developer failed to use the low emission glass to mitigate heat gain from minimally operable floor to ceiling windows. In a cool city such as San Francisco, being able to open windows to achieve air movement within a room would go a long way toward solving the problem.

Trump Administration Could Effectively End Housing Voucher Program

Federal officials are eyeing major cuts to the Section 8 program that helps millions of low-income households pay rent.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Ken Jennings Launches Transit Web Series

The Jeopardy champ wants you to ride public transit.

Crime Continues to Drop on Philly, San Francisco Transit Systems

SEPTA and BART both saw significant declines in violent crime in the first quarter of 2025.

How South LA Green Spaces Power Community Health and Hope

Green spaces like South L.A. Wetlands Park are helping South Los Angeles residents promote healthy lifestyles, build community, and advocate for improvements that reflect local needs in historically underserved neighborhoods.

Sacramento Plans ‘Quick-Build’ Road Safety Projects

The city wants to accelerate small-scale safety improvements that use low-cost equipment to make an impact at dangerous intersections.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Heyer Gruel & Associates PA

Ada County Highway District

Institute for Housing and Urban Development Studies (IHS)

City of Grandview

Harvard GSD Executive Education

Toledo-Lucas County Plan Commissions

Salt Lake City

NYU Wagner Graduate School of Public Service