As cities work hard to evolve their perspective on the role of streets as public places in smarter city-making, remember this: Good cities know that streets move people, not just cars. Great cities know that streets are places to linger and enjoy.

Here in Vancouver, we have a pretty enlightened perspective on streets, at least by North American standards. For many decades, and particularly since the game-changing 1997 Transportation Plan, Vancouver city planners and traffic engineers alike have understood that streets aren't just for moving cars – they're for moving people.

With Vancouver's supportive land-use decisions and deliberate prioritization of walking, biking and transit-riding over driving, movement in our streets means moving more and more people by active modes, or "human power." Given these modes take up a lot less space and public cost, this means our streets are much more efficient for moving people than those designed to prioritize cars – something our enlightened transportation engineers love.

But here's the thing – streets aren't just for moving people. In our more recent Transportation 2040 Plan, which I was deep into before leaving City Hall, our goal was a deliberate next evolution of thinking – streets for people to enjoy and linger, not just move through.

You see, up until a few years ago, my excellent colleagues in the Transportation Planning Department still tended to think of success in streets as being about movement, albeit much more sustainable, healthy and cost-effective movement (who can blame them, I suppose – transportation is in their title), and as something you can count (well, most of them ARE engineers, after all). The concept of place-making, of deliberately wanting people to stop and enjoy the street rather than move through it, was harder to count, and thus harder to conceptualize as success.

No issue revealed this tension more than that of restaurant or café patio space on busy walking streets. Although such patios are an excellent way to turn streets into places to linger and people-watch, if your priority is to move people along sidewalks, especially sidewalks with widths that are not particularly generous, patios can be seen as a hindrance.

But when you see streets as people-places, those things that slow down a pedestrian’s pace may be the very things that make a street great. Things like patios, food carts or trucks combined with attractive seating, street performers, or just really lively store windows that draw a crowd, all contribute to making a street more "sticky." And by that, I don't mean gum on the sidewalk! A street is sticky if as you move along it, you're constantly enticed to slow down, stop and linger to enjoy the public life around you.

At first, this kind of success can make an engineer nervous – can you count it? Model it?

As a city-maker, one of my favorite quotes is "not everything that counts can be counted." For those who love to count things though, there are proven methodologies out there on how you can quantify and measure the amount of time that people stay in a space or street. One of my favorite new books focuses on the subject, "How to Study Public Life" by my friend and mentor Jan Gehl, co-written with Birgitte Svarre. I highly recommend it.

As the book notes,

As the book notes,

"Starting with the question of how many is basic to public life studies. In principle, everything can be counted, but what is often registered is how many people are moving (pedestrian flow) and how many people are staying in one place (stationary activity)."

In other words, one of the most valuable things to measure and count on a street, is how long people stay. A particularly memorable piece of advice Jan once gave to me, is that you can double the number of people in a public place either by doubling the number of people who are drawn to the place (which can be challenging given the need to get their attention, and then address the transportation/parking needs and implications of having them come), OR by doubling the length of time that people choose to stay. The latter is easier (or at least it should be, if place-making was understood better) – you simply have to make a place that people want to stay in longer. So the key, once people choose to come to a street or place, is to entice them to linger.

That's what sticky streets are all about. Streets that are almost a challenge to get through, not because of barriers or because, like malls, they're designed to make you feel lost, but because of so many enticing opportunities to participate in public life! Opportunities that seduce you to stop, watch, smile, enjoy and possibly participate – to be part of things.

Much of our efforts as urbanists in recent years has been promoting the concept of more walkable cities. As we think about street design however, great streets should be both walkable AND sticky. In fact, the two are completely synergistic, as there are few things that make walking safer and more enjoyable than walking along other people sitting and enjoying the street – even if you have to occasionally walk around them. Even if you don't choose to stop, it can make the walking experience so much better.

So what makes a street sticky? A great shopping street where every store has something going on to draw the eye. Windows with something interesting and active inside, sometimes referred to as "street theatre." Lively patios for people-watching (and don't forget, colder cities like Copenhagen have shown that patios need not be seasonal – try blankets!). Lots of casual seating and informal food opportunities such as food carts and trucks. The right combination of sun, shade, wind protection, water (especially to create "white noise" for noisy streets) and micro-climates designed for the specific local context. Things to look at and engage with, such as public art (preferably interactive).

All these can work, but never forget three things:

First, the most interesting thing for people to look at is other people.

Second, remember that the least sticky thing a street can have is blank walls, either in the initial building design, or through windows blocked with "lifestyle images" or stacked toilet paper (yes, drug stores, I’m talking to you). One might call these "teflon streets." Don’t allow them.

Third, remember not every street needs to be as sticky as every other. Pick your streets for greatest emphasis, but every street should have enough to be walkable and reward the pedestrian's eye.

Not surprisingly, these factors for sticky streets are the same as those that make sticky public places and squares, as studied for decades by great placemakers like William H. Whyte and his successors at the Project for Public Spaces (PPS). After all, streets are just public spaces - the most common kind in cities.

So as city planners and urban designers, or as any kind of place-maker, while you're having your discussions with your transportation colleagues, working hard to evolve your shared perspective on the role of streets in smarter city-making, remember this: Good cities know that streets move people, not just cars. Great cities know that streets are also places to linger and enjoy.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

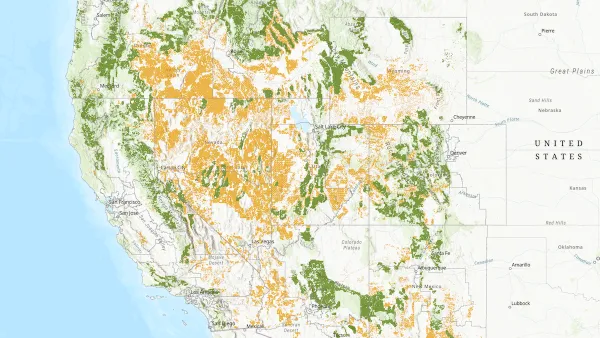

Map: Where Senate Republicans Want to Sell Your Public Lands

For public land advocates, the Senate Republicans’ proposal to sell millions of acres of public land in the West is “the biggest fight of their careers.”

Restaurant Patios Were a Pandemic Win — Why Were They so Hard to Keep?

Social distancing requirements and changes in travel patterns prompted cities to pilot new uses for street and sidewalk space. Then it got complicated.

Platform Pilsner: Vancouver Transit Agency Releases... a Beer?

TransLink will receive a portion of every sale of the four-pack.

Toronto Weighs Cheaper Transit, Parking Hikes for Major Events

Special event rates would take effect during large festivals, sports games and concerts to ‘discourage driving, manage congestion and free up space for transit.”

Berlin to Consider Car-Free Zone Larger Than Manhattan

The area bound by the 22-mile Ringbahn would still allow 12 uses of a private automobile per year per person, and several other exemptions.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Heyer Gruel & Associates PA

JM Goldson LLC

Custer County Colorado

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

Transportation Research & Education Center (TREC) at Portland State University

Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Claremont

Municipality of Princeton (NJ)