The mantra “eyes on the street" focuses on the physical and functional traits of urban fabric but fails to explain the high crime rate of my Jacobsian neighbourhood. Time to reconsider, look for explanations, and exchange mantras for research.

I live in an ideal Jacobsian neighbourhood: Centertown, Ottawa. It posts the second highest density among city districts, the widest mix of land uses, and an unmatched range of incomes and ethnic backgrounds. It is laid out on a grid and includes buildings that span the entire gamut of types, functions, forms, and history; no other ward in this city is as diverse. Yet, something essential is missing from the anticipated outcomes of an urban fabric such as this—security. Here we seek to find out why.

This district has at least three east-west and four north-south "main street" arteries, where small businesses thrive, professional services are offered, and numerous people live above shops, just as in Jane Jacobs’ actual Manhattan neighborhoods. Invariably, these streets buzz with activity all day. Routine destinations are within a ten- to 20-minute walk. Everything that the "eyes on the street" neighbourhood model recommends is present. As theory has it, improved security should be a natural, expected outcome.

Yet I live in the most dangerous neighbourhood of my city—not by mere percentage points but a manyfold difference. And, surprisingly, this abnormal difference belies the fact that my city registers the second lowest crime rate among the top eight major Census Metropolitan Areas. How can that be explained, knowing that no other district in this city comes even close to its level of "eyes on the street" potential? By contrast, and belittling theory, the most typical suburban city neighbourhood occupies the lowest rank of the scale. Perhaps research has answers to this baffling incongruity.

Research

In a Jane Jacobs biography titled Eyes on the Street, the question of whether evidence supports the proposition that "eyes on the street" reduce crime is professionally disputed.

I quote: "May be not, a University of Pennsylvania Law Review suggested; pedestrian-dense, mixed-use development in Los Angeles neighbourhoods did record lower crime than those exclusively commercial; but purely residential areas had crime rates lower than either. A meta-study of research drawn from the broad discipline of environmental criminology came away similarly skeptical."

A single study can be disputed as a basis for drawing credible conclusions, but the results of a meta-study are usually reliable. Whatever research could unveil would be interesting academically. My mission is closer to home. I live in an Alchemist's jar with a mix of ingredients presumed to produce safety gold but instead it delivers lead. Transmutation attempts failed because the nature of elements was misunderstood. Could this be the case of the factors that nurture crime in a neighbourhood? It's time to look in different directions for clues.

Districts and Streets in History

New York’s West Village and my district share certain physical characteristics that purportedly increase safety: density, diversity of built form, and proximity to daily destinations. These were also defining characteristics of most cities in history but, in notable cases, with strikingly different streetscapes than contemporary ones.

For example, a thriving commercial port city, Pompeii, representative of a Roman period (~50 AD), had 11 000 people in its small, walled-in area—over triple Centertown’s density. But its streets could hardly differ more from those I tread on daily: narrow, leafless, drab, malodorous, and ominous, particularly after dusk. No windows faced the street, just the infrequent opaque door—an ideal setting for illicit activity.

Similar streetscapes prevailed in Fez (still intact), the largest city in the world around 1100 AD (~200k pop) and also a major commercial and cultural centre. Its streets were laid out in a perplexing maze and were just as narrow and opaque as Pompeii’s. Small windows were put, by code, above pedestrian eye level to prevent prying into houses. Such streets and layouts were common in ancient and medieval cities. Not only were they opaque and crooked, they were also empty. Most streets functioned simply as necessary conduits, not places for socializing.

Lacking any casual, informal surveillance, districts such as these must have been most antisocial, dreary, even deadly places. This was decidedly not the case, history tells us—In fact, it was quite the opposite. People in these cities were close-knit, bonded by religion, tradition, familial relations, and customs.

It would seem that neither research, nor history, nor the Centertown case statistics support the "eyes on the street" proposition.

Eyes from the Street

While the Roman and Arab court-centered buildings without windows blocked eyes from the street, contemporary houses achieve the same effect with a variety of means appropriate for them—distance, walls, fences, hedges, and elaborate curtains. Most vulnerable to intrusion are detached houses and, among them, those at street corners. The rationale for these commonplace measures is explained in Jacobs’ book: "Privacy is precious in cities. It is indispensable. Perhaps it is precious and indispensable everywhere, but in most places you cannot get it[...]"

Other Directions for Clues

Streets and the buildings that frame them, including their functions, are but the stage on which uncivil, offensive acts are performed; it is human actors that carry them out. These actors form the intricate social fabric of a neighbourhood—each actor with their individual, but always invisible, characteristics. The same built form could house populations with starkly different characteristics over time, as districts evolve, and produce distinct safety outcomes. Perhaps it is the social fabric that could unravel the mystery of Centertown. It has been repeatedly shown that poverty and its related conditions are associated with errant behaviour in its many guises.

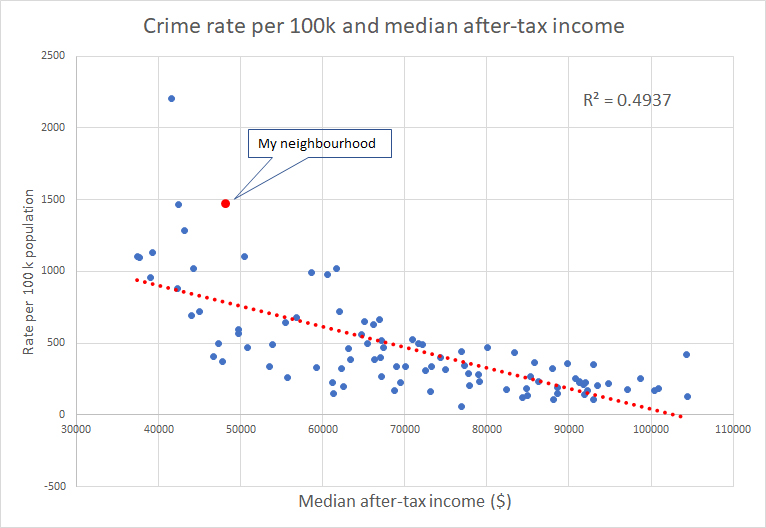

Detailed stats show that Centertown occupies the low end of the median income scale and the high end of the crime scale. Next to it, a neighbourhood also in a central location with similar physical characteristics, exhibits even lower income level and similar crime rates suggesting a consistent trend, evidenced in the graph. (Fig 4)

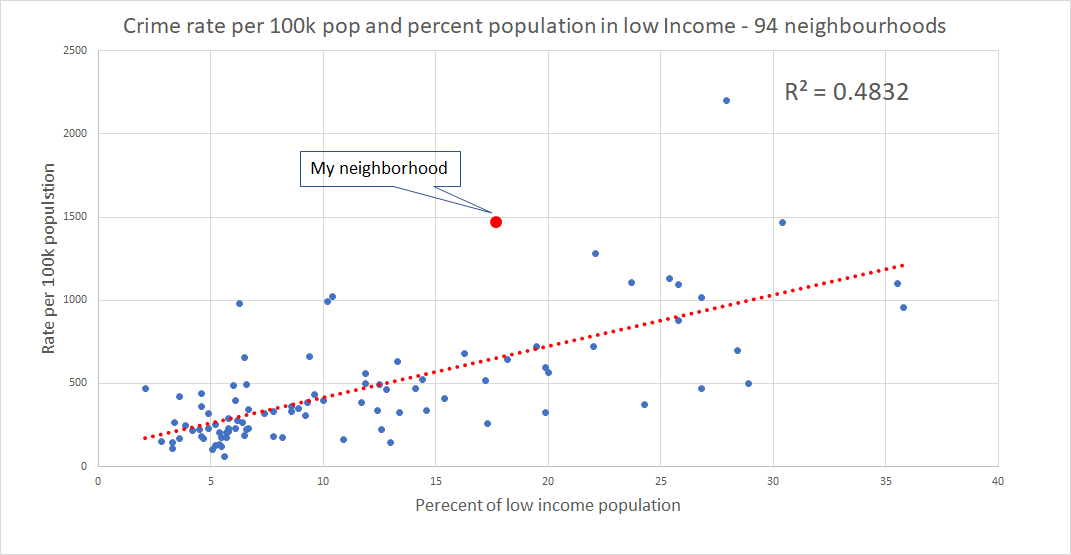

Median income values could result from relatively uniform or widely ranging incomes, potentially hiding part of the social fabric’s texture. Another measure of neighbourhood income—the percentage of people living in low-income—might spotlight the difference of incomes within a neighbourhood.

Combining the evidence from these two strong correlations leads to the realization that the social fabric of a neighbourhood is a much better predictor of its relative crime level than its physical fabric. It does not eliminate the physical factors; it simply reduces their degree of importance for this outcome.

Other social fabric descriptors, such as education, employment, Gini coefficient, cohesion, and more could add explanatory power to social fabric as a determinant of the frequency of antisocial acts. Equipped with such power, we might be able to say, "show me the social characteristics of your neighbourhood and I will tell you the odds of being victimized." I was victimized twice in this Jacobsian neighbourhood and now I understand why.

Fanis Grammenos is the director Urban Pattern Associates in Ottawa, Ontario and the author of Remaking the City Grid: A Model for Urban and Suburban Development. Reach him by email with questions or comments.

Trump Administration Could Effectively End Housing Voucher Program

Federal officials are eyeing major cuts to the Section 8 program that helps millions of low-income households pay rent.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

The 120 Year Old Tiny Home Villages That Sheltered San Francisco’s Earthquake Refugees

More than a century ago, San Francisco mobilized to house thousands of residents displaced by the 1906 earthquake. Could their strategy offer a model for the present?

HSR Reaches Key Settlement in Northern California City

The state’s high-speed rail authority reached an agreement with Millbrae, a key city on the train’s proposed route to San Francisco.

Washington State Legislature Passes Parking Reform Bill

A bill that would limit parking requirements for new developments is headed to the governor’s desk.

Missouri Law Would Ban Protections for Housing Voucher Users

A state law seeks to overturn source-of-income discrimination bans passed by several Missouri cities.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Ada County Highway District

Clanton & Associates, Inc.

Jessamine County Fiscal Court

Institute for Housing and Urban Development Studies (IHS)

City of Grandview

Harvard GSD Executive Education

Toledo-Lucas County Plan Commissions

Salt Lake City

NYU Wagner Graduate School of Public Service