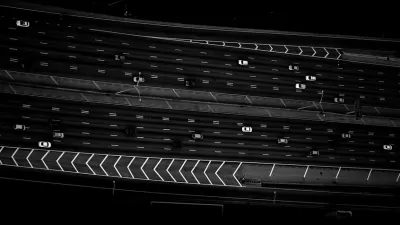

An ambitious vision for freeways: intersections with dense, tall buildings and rights of way repurposed for high-speed, high-capacity public transit.

The stark images of nearly empty freeways in the Spring of 2020 offered an opportunity to reevaluate many aspects of daily life—like the environment, the housing market, and mobility. Hopefully, the experience offered an opportunity to question at least two truisms about daily life in the United States.

Truism 1: Freeways Only Have Cars, Buses, and Trucks

Seeing the nation's empty freeways last year should provoke a question: Should cars, buses, and trucks be the only vehicles using freeways? The default answer since the 1950s has been an unequivocal "yes." However, given evolving mobility choices, policymakers could reevaluate how freeways are used.

America's big push into high-speed rail and very rapid public transport has been fraught with challenges. Some of those challenges have been encountered in the uncharted territory of high-speed rail regulation, contractor experience, and tunneling costs. However, many challenges are created by the securing of right of ways, notably in California.

All too often, behavior changes only after seeing a real alternative in action. One of high-speed rail proponents' largest mistakes was not focusing on regions with potentially high demand. As a commuter languishing in traffic five days a week, I have very little impetus to use a system that I cannot see, no matter how fast it might be going. However, if I am stuck in traffic and see a train whizzing by at 80 miles an hour, the message is loud and clear, and most importantly leads at least to the serious consideration of a change in behavior.

The trains themselves could serve as the perfect advertisement—passing hundreds of thousands of potential clients daily. The "drip, drip, drip" messaging over the course of days and weeks would take hold.

Surface streets used to have only cars and buses, now they have significantly more sidewalks for pedestrians and dedicated bike and bus lanes, not to mention more trees. Why not rethink freeways, if regular, reliable and user-friendly feeder systems are available near the freeway?

Truism 2: Larger Living Space Is "Better" Living Space

Another truism has been the clear preference for larger living quarters, characterized by the single-family home. Indeed, the post-World War II era largely followed the pattern "commercial real estate rises up, residential real estate spreads out."

With inner cities suffering a perceived lack of "livability," and because of exorbitant housing, many families feel compelled to buy a cheaper house in other regions to achieve a better quality of life. With that housing choice comes an extensive commute to boot. Not for the fainthearted, these commutes can take three or four hours a day—12%-16% of one's life, inching along a 10-lane concrete ribbon. Almost the lone American exception to this reality is New York City, which couples dense living with an extensive public transit system. These commutes have had a reprieve during the pandemic, but the majority of them will eventually come back.

Developers should shake off the cookie cutter approach of the "3+2 with a backyard" or "loft living" and start thinking about the fortune in the affordable housing market. Does a family "need" 1,500 square feet when it comes with a three-hour commute? Or does it simply "want" it? Even worse, does it feel that a single-family residential lifestyle is somehow "deserved"? The energy costs of a house that size will only increase in the coming years. Indeed, to take one example, California’s energy prices have risen 2.8% per year since 1994. It’s hard to imagine these prices stabilizing given the tenuous situation with PG&E.

Coming generations will have to profoundly reconsider this tradeoff—square feet vs. time. That same 1,500 feet could be divided into two apartments, with equally if not more, of a profit margin for a developer. It is significantly cheaper to build up, as opposed to build out. And what if that reduced space came with a two-thirds reduction in commuting time? Indeed, time should be more widely considered as a currency. Developers are currently building more apartments, but access to affordable and smaller apartments could be significantly increased.

Policymakers can encourage more responsible urban living through measures that promote a sustainable urban landscape, saving time and money and reducing environmental impacts. One such measure would be the idea of a sprawl tax—sprawl costs billions in utilities and roads, and air pollution due to long commutes. If the term "sprawl tax" offends, maybe "density dividend" works better.

Radical Rethink: Couple Mobility and Housing

To solve this Gordian Knot, mobility and housing could be and should be coupled. Many of America’s largest cities have major interchanges usually with adjacent unused patches of land. Using the city of Los Angeles as an example, some of its major interchanges include the 405/10, 101/110, and 405/101 freeways.

Building a 20+ story predominantly residential tower at interchanges, dedicated to affordable housing (prioritizing essential public servants—health, education, and policing) with some mixed use, might help to alleviate the paucity of housing.

Complementing these new vertical spaces in key nodes around the city would be a transport system that rapidly moves the adjacent population to another node. From the 405/10 node, one could travel 11 miles north to the 405/101 interchange or east 12 miles to the 10/110 (downtown) in just minutes. That mode of transport could be a fast train or, should the technology be proven, a hyperloop, traveling down the freeway’s center divider. Even dedicated bus lanes (with dozens of buses) would allow a quick start on the effort and avoid the exorbitant costs of large capital projects.

High Speed Rail Learning

Most importantly, for such an approach, there would be no right of way issues and usually one interlocutor—the state. Using existing right of way would avoid the need to purchase of individual pieces of land with countless lawsuits. As late as 2019, California’s High Speed Rail still had to purchase over 450 parcels of land. Such a system would take the equivalent of three to four lanes of a ten-lane freeway, would substantially decrease air pollution, and, most importantly, would save time by moving people around at dramatically increased speeds.

Before the naysayers start, recall that an NFL stadium was once seriously considered at the 405/10 interchange, potentially used 10-12 days annually in one of the country's most strategic interchanges. What about a vertical "city" there, acting as a residential option and transport node to facilitate commuting around one of the world’s largest cities? The hardware (freeway) is there—the software (policy) is now needed. Developers should be provided incentives to create flagship housing that doesn’t contribute to sprawl.

How We (Choose to) Live in the 21st Century

Over the last 18 months, futurists have equated Covid-19 to a great accelerator. Perhaps it is, but the question remains: Toward what? More Business as Usual?Or, a Brave New World, in which mobility, housing, and the environment meet? The "pause" button of 2020 allowed us to reimagine some of the possibilities. There is only so long that people can shelter in place. Housing is only one side of the coin—the other side being mobility. The current situation allows us the very unique ability to ask ourselves: What if?

Los Angeles has made a considerable leap forward in establishing a public transport network—a massive improvement compared to a generation ago. The burgeoning system needs a stronger push toward a rapid, regional solution to complement that progress.

Policymakers and indeed all of us will have to consider what is best for future generations. A major portion of that effort will require setting priorities for the built environment. A more enlightened freeway policy coupled with (affordable) housing that goes up, not out, would be a dramatically positive step forward.

Let's hope that we juggle both urgent short-term action and equally urgent long-term thinking. Getting the balance right is crucial for coming generations.

Richard Dion is an advisor in the Governance and Human Rights Unit at GIZ, the German Corporation for International Cooperation GmbH.

Trump Administration Could Effectively End Housing Voucher Program

Federal officials are eyeing major cuts to the Section 8 program that helps millions of low-income households pay rent.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Ken Jennings Launches Transit Web Series

The Jeopardy champ wants you to ride public transit.

Washington Legislature Passes Rent Increase Cap

A bill that caps rent increases at 7 percent plus inflation is headed to the governor’s desk.

From Planning to Action: How LA County Is Rethinking Climate Resilience

Chief Sustainability Officer Rita Kampalath outlines the County’s shift from planning to implementation in its climate resilience efforts, emphasizing cross-departmental coordination, updated recovery strategies, and the need for flexible funding.

New Mexico Aging Department Commits to Helping Seniors Age ‘In Place’ and ‘Autonomously’ in New Draft Plan

As New Mexico’s population of seniors continues to grow, the state’s aging department is proposing expanded initiatives to help seniors maintain their autonomy while also supporting family caregivers.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Heyer Gruel & Associates PA

Ada County Highway District

Institute for Housing and Urban Development Studies (IHS)

City of Grandview

Harvard GSD Executive Education

Toledo-Lucas County Plan Commissions

Salt Lake City

NYU Wagner Graduate School of Public Service