Americans are moving a lot less than they once did, and that is a problem. While Yoni Applebaum, in his highly-publicized article Stuck, gets the reasons badly wrong, it's still important to ask: why are we moving so much less than before?

This is part one of a two-part post.

One principle that I have found well worth following is simple: watch out for hedgehogs. Not those cute little animals, but as in Isiaih Berlin’s famous essay, where he quotes the ancient Greek poet Archilochus, who wrote that ‘The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing.’ In other words, whatever the question, watch out for people who think they’ve discovered The Answer, or The Reason Why.

In his recent cover article in The Atlantic, “Stuck in Place”, Yoni Applebaum, a journalist with a history degree, has not only found The Reason Why for America’s social and economic malaise, but also pinpointed the villain of the story. Summarized extremely briefly, the reason is the decline in internal geographical mobility, especially people picking up and moving from declining places to growing places; the reason for declining mobility is the high cost and unavailability of housing in growing places; the villains are progressive policies; and the ur-villain, the Darth Vader of the story, (drumroll) is Jane Jacobs.

Now that is an oversimplification, of course, but not much of one, and Applebaum may present his case with more nuance in his book, which I have not read yet. But since he published the article to stand by itself, I consider it fair to address it on its own terms. Moreover, in only a few months it has received an extraordinary amount of approving attention within the liberal ecosphere, that cluster of center-left media, think tanks and institutions who care about these issues.

There is some truth to all of the elements in his argument that I’ve summarized above, except the last. The problem that he identifies is a real one. What’s wrong with his argument, though, is that he oversimplifies the reasons for the underlying problem, misses the real culprits, and mis-diagnoses the solution.

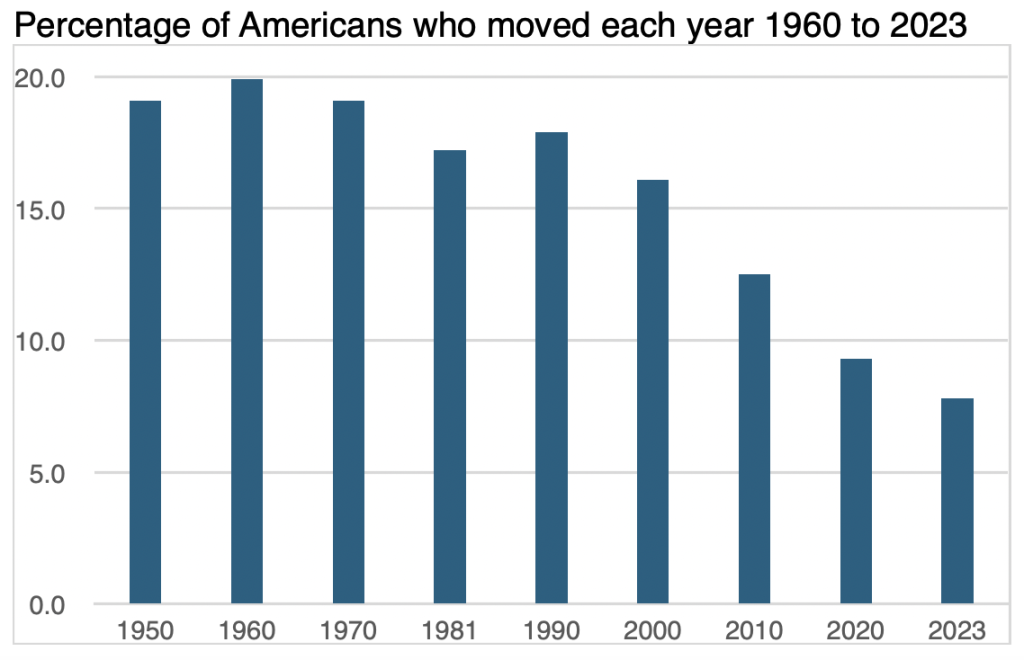

Applebaum’s starting point is, up to a point, indisputable. Residential mobility, in the sense of people moving from house to house within the country, has declined dramatically since the 1950s, although the trajectory of change is different from what he implies. In the 1950s, 20 percent or roughly 1 out of 5 Americans moved every year. In the most recent American Community Survey, in 2023, fewer than 8 percent, or slightly more than 1 out of 13 moved.

This is an important shift, which he characterizes as “the single most important social change of the past half century.” I would argue that both the aging of the population, and the change in our racial/ethnic makeup are equally or more important, but let that pass. He then links that change, without elaboration or documentation, to worsening social mobility, declining entrepreneurship, declining church membership, lower birth rates, and voting for Trump. Those connections are, at best, debatable. To the extent, however, that declining mobility means that fewer people are moving from declining places to places of greater opportunity- an important qualifier - there is little question that it has significant costs for both the US economy generally, and for the people who might under different circumstances have moved.

Whether or not that has anything to do with church attendance or birth rates, it is important. But the question is, why is it happening? Here he goes off the rails. Preceded by a sentence that reads, in its entirely, “blame Jane Jacobs,” he goes on to write that “American mobility has been slowly strangled by generations of reformers, seeking to reassert control over their neighborhoods and their neighbors. And Jacobs, the much-celebrated urbanist who died in 2006, played a pivotal role.”

Now, at this point, there is a growing awareness among people who’ve looked at the issue that American environmental regulations and zoning practices – particularly the vast amount of land in metropolitan areas exclusively zoned for single-family homes – have played an important role in creating the high housing costs and undersupply which are a key factor in triggering today’s housing affordability crisis. Indeed, that debate is more between those who believe it is the sole cause of the crisis – and that, therefore, removing those obstacles will solve the crisis – and those like myself who believe it is a contributor but not the sole cause – and that solutions will require far more than just zoning reform. But that’s a debate for another day.

Applebaum looks at it differently, however. He has what might be called a utilitarian view of cities and their neighborhoods, seeing them as little more than containers that should constantly grow “to accommodate demand, to make room for new arrivals” and that “a neighborhood] it bears the same relationship to its buildings as does a lobster to its shell, periodically molting and then constructing a new, larger shell to accommodate its growth,” “But Jacobs,” he goes on, “charmed by this particular lobster she’d discovered, ended up insisting that it keep its current shell forever.” Clever, partially right but mostly wrong, and mainly almost totally irrelevant to the issue of mobility.

The problem is that he sees the land use and environmental obstacles to mobility in terms of the growth of existing built neighborhoods, and not the growth of metropolitan areas as a whole. During the decades before and after Jacobs’ book, however, Americans by the millions were fleeing older urban neighborhoods for the suburbs and the Sunbelt. And they were able to move there because millions of new houses were being built, not in older neighborhoods, but on hitherto undeveloped land at the urban periphery. Between 1950 and 1970, 450,000 new homes were built on Long Island alone. During the same years, 1.4 million new units were built in Los Angeles County, with Orange County adding over 400,000 to the mix.

Mobility was made possible by rapid suburban expansion and Sunbelt growth, dominated by modestly priced single family homes and garden apartments that offered affordable rents. Of course, there were a lot of other factors involved in mobility, but let’s stick to housing supply for the moment. One does not have to think of Jacobs as St. Jane of Hudson Street to recognize that neighborhoods have value as neighborhoods, with all that implies, not just as containers, while the preservation of a handful of urban neighborhoods, a welcome corrective to the urban renewal wrecking ball, was no more relevant to the course of American mobility than the sunspot cycle. Jane Jacob’s West Village was an extreme outlier among American urban neighborhoods. Across America, the reason older neighborhoods didn’t grow is that people didn’t want to live there. And because people didn’t want to live there, builders didn’t want to build there.

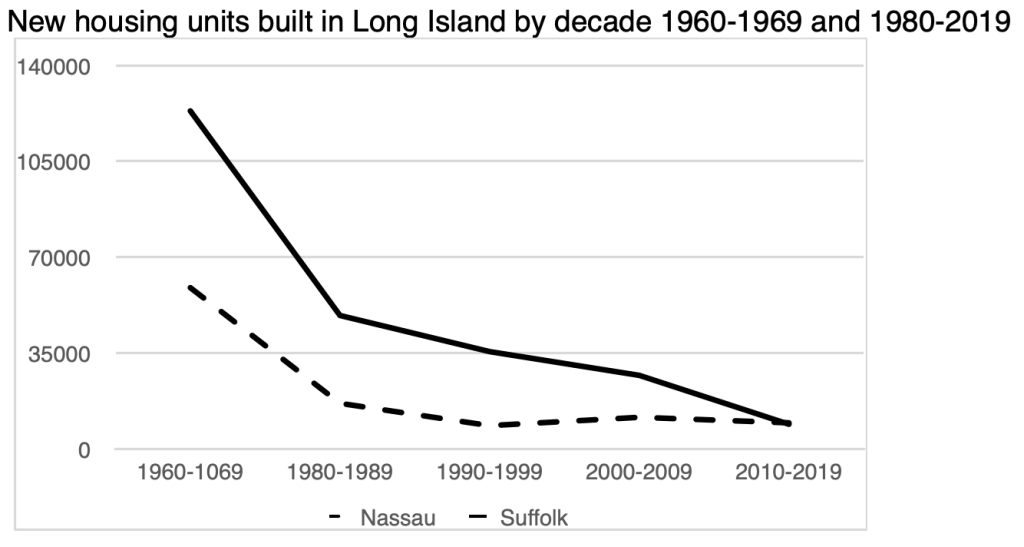

So what actually happened? Suburban housing production fell off a cliff. The table shows housing production by decade for Nassau and Suffolk Counties, which collectively make up Long Island (unfortunately, data for the 1970s is not readily available). In the 1960s, nearly 200,000 new homes were built on Long Island. By the 1980s, the total had dropped to 65,000, or only one-third as many, and by the 2010s, to 18,000, a drop of 90 percent from the 1960s. While the original Levittown sales price was $7900, equivalent to a little over $106,000 today, the median house price in Nassau County at the beginning of 2025 was over $800,000.

The picture in Southern California was not as extreme, but similar. Since 1990, average housing production in Los Angeles and Orange counties has been only 25,000 per year, less than one-third of what it had been in the 1950s and 1960s. A lot of this has to do with increasing scarcity and cost of buildable land and the steadily rising cost of construction. But much of it is about restrictive land use and environmental regulations, particularly on Long Island, where zoning for multifamily housing is all but nonexistent.

So who is to blame for those excessive zoning and environmental regulations? Progressives played a role, to be sure, particularly in the environmental movement, and scoring points for finding examples of NIMBY hypocrisy among people voicing liberal pieties is a cheap sport. But while self-flagellation is a popular pastime on the left, to assert, as Applebaum does, that “progressives froze the American dream” is both tendentious and untrue.

Most fundamentally, the exclusionary policies that have dampened housing opportunities have been driven by the desire by homeowners and suburban local governments to create and preserve wealth by maximizing house values, aided and abetted by a generation of planners. Indeed, when zoning exclusion first became a public issue in the 1960s and 1970s, it was rightly understood as a right-wing, anti-urban and anti-Black practice. The fight against it by the Suburban Action Institute and the National Committee against Discrimination in Housing and others came from the left, an offshoot of the civil rights movement of the 1960s. That fight left a modest legacy, most notably in New Jersey’s housing fair share laws and Massachusetts’ “anti-snob zoning” law. Almost needless to say, the fight was couched as an effort to enable lower-income people – and people of color – to escape urban neighborhoods, a counterpart to the simultaneous struggle to help them escape failing urban schools.

Those times are long-gone, of course. Well-to-do suburbanites are more likely to vote Democratic today than they were in the 1970s or 1980s, and housing affordability has become an increasingly difficult challenge for millions of middle-class households who back in the 1970s and 1980s could usually find housing they could afford. Moreover, the gap in housing costs and economic conditions between growing and stagnating regions in the United States has grown to mammoth proportions. But that is hardly the result of progressive policies, but the outcome of neoliberal globalization, a right-wing project (although one in which much of the left was complicit).

How this relates to mobility is much more complicated than Applebaum appears to realize. Contrary to the impression he leaves in his article, rather than a steady drop in mobility since the 1960s, mobility didn’t change that much until 2000, when the real drop began. This tells that there are a lot of things going on other than housing regulation that are driving the drop in mobility. In Part II of this post, I will drill down to look at the other factors that are driving mobility and how they have changed over the years.

Migration, housing, land use, and the like are all complicated issues, with multiple interests at stake, and multiple outcomes. Pace Applebaum, there is no one big

Answer that explains it all, and no single villain to point to. Yes, simple answers are nice. But instead of applauding every wannabe pundit who comes along with the latest Answer, wouldn’t it be better to look closely at these issues, and try to really understand what’s going on?

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Restaurant Patios Were a Pandemic Win — Why Were They so Hard to Keep?

Social distancing requirements and changes in travel patterns prompted cities to pilot new uses for street and sidewalk space. Then it got complicated.

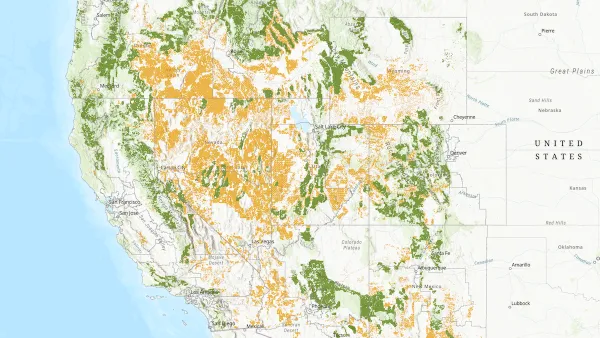

Map: Where Senate Republicans Want to Sell Your Public Lands

For public land advocates, the Senate Republicans’ proposal to sell millions of acres of public land in the West is “the biggest fight of their careers.”

Maui's Vacation Rental Debate Turns Ugly

Verbal attacks, misinformation campaigns and fistfights plague a high-stakes debate to convert thousands of vacation rentals into long-term housing.

San Francisco Suspends Traffic Calming Amidst Record Deaths

Citing “a challenging fiscal landscape,” the city will cease the program on the heels of 42 traffic deaths, including 24 pedestrians.

California Homeless Arrests, Citations Spike After Ruling

An investigation reveals that anti-homeless actions increased up to 500% after Grants Pass v. Johnson — even in cities claiming no policy change.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Heyer Gruel & Associates PA

JM Goldson LLC

Custer County Colorado

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

Transportation Research & Education Center (TREC) at Portland State University

Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Claremont

Municipality of Princeton (NJ)