Professor Wes Marshall’s provocatively-titled new book, "Killed by a Traffic Engineer," has stimulated fierce debates. Are his criticisms justified? Let’s examine the degree that traffic engineers contribute to avoidable traffic deaths.

Professor Wes Marshall’s new book, Killed by a Traffic Engineer, has created a kerfuffle on the Institute of Transportation Engineers website. Responses range from outrage to support. Some members dismissed the book altogether (“There is no need to read this book” and "I call on Mr. Marshall to either revise the title of his book or resign from the Institute"), while others give it grudging respect. One engineer explains, “It is a fantastic read so far. It gives a great review of the last 100 years of traffic and transportation engineering and how we got to this point.” Professor Susan Handy describes the book as “A blistering critique of the disconnect between what transportation engineers do and what the research tells us about traffic safety. This eminently readable book is a wake-up call for all of us.”

(For a more humorous takedown of traffic engineering see transportation planner and rapper Buff Brown’s, The Barrier of the City Engineer, which uses the Engineering Bingo Card of Excuses and other rhyming insights to explain why, when it comes to traffic safety the U.S. is status quoing.)

Are Marshall’s criticisms justified? Let’s examine the degree to which traffic engineers contribute to avoidable traffic deaths.

Do we have a problem?

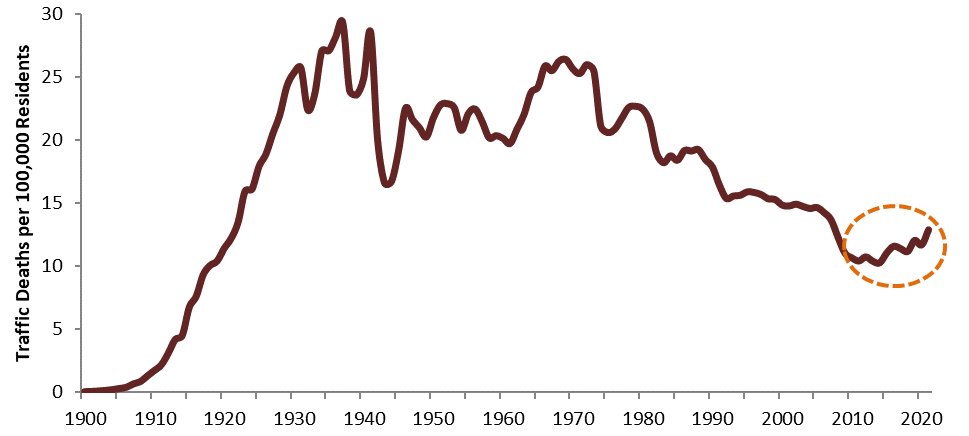

The first step in solving a problem is to acknowledge that it exists. When it comes to traffic safety, the United States is clearly failing. After decades of decline, per capita traffic death rates increased after 2014 as illustrated below.

Per Capita U.S. Traffic Fatality Rates

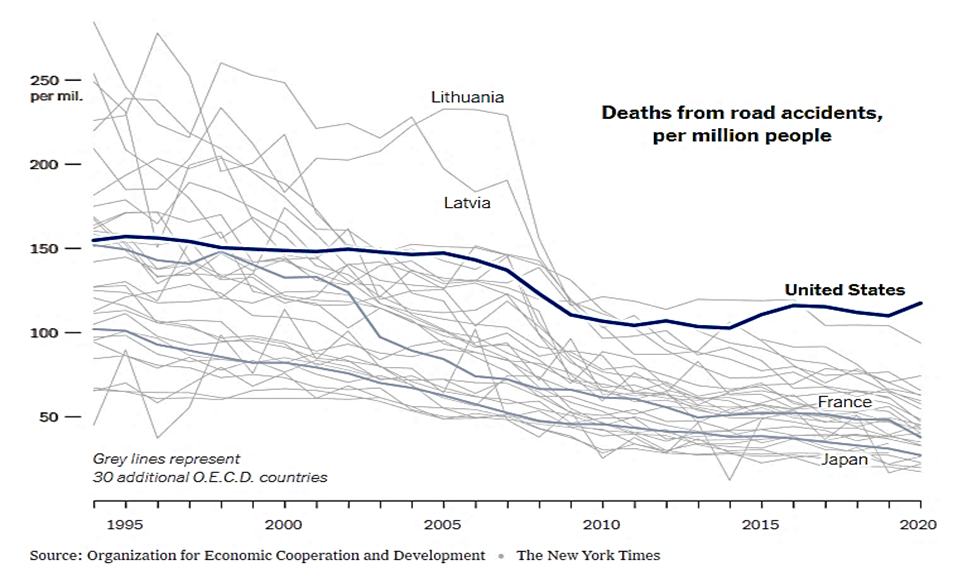

Other countries have achieved much greater safety gains. The U.S. now has crash rates two to four times higher than most peers, as illustrated below.

Similar patterns occur at other geographic scales. For example, traffic death rates range from less than five to more than twenty per 100,000 state residents, as illustrated below.

Traffic Death Rates by U.S. States

What explains these large differences? Are traffic engineers in high crash rate states such as Wyoming and Mississippi less capable and concerned about safety than in lower crash rate states such as Rhode Island and Massachusetts? Probably not. A better explanation is that high crash rates reflect increased exposure -- more annual miles driven at higher speeds -- than in safer states, as indicated in the following graph.

Traffic Fatalities Versus Mileage for U.S. States

There are similar variations between regions within a state and between neighborhoods within a region. Compact, multimodal neighborhoods typically have an order of magnitude lower death rates than automobile-dependent, sprawled neighborhoods where residents drive more annual miles at higher speeds, and high risk groups (young males, frail seniors, people impaired by alcohol or drugs, etc.) have no convenient alternative to driving.

Of course, many factors affect an individual's crash risk including their caution, skill, vehicle type, and road conditions, but at a population level, a change in mileage tends to cause proportional changes in crashes. For example, a lower-risk driver may average a casualty crash every 500,000 vehicle-miles and a high-risk driver may average a casualty crash every 50,000 vehicle-miles, but if both reduce their mileage by 20 percent their combined crashes should decline at least that amount. As a result, planning practices that induce more vehicle travel tend to increase per capita crashes, and vehicle travel reduction strategies increase safety.

This is a key point in Marshall's book: conventional transportation engineering often evaluates traffic risk using distance-based metrics such as collisions, casualties, or deaths per 100 million vehicle-miles or million vehicle-trips. Such indicators ignore exposure as a risk factor and so fail to recognize the additional crashes that result from planning decisions that increase per capita vehicle travel or the safety benefits of vehicle travel reductions. The new traffic safety paradigm measures casualties and deaths per capita, as with other health risks, and therefore the safety impacts of changes in mileage.

The need for more systematic analysis

How could transportation agencies do better? Traffic safety requires more comprehensive analysis. Conventional traffic safety analysis is reductionist: it looks at individual risk factors. Professor Marshall is one of many researchers who are starting to apply more systematic analysis. Let me give some examples.

Motorists sometimes crash into trees. The reductionist analysis concludes that trees cause crashes and wider clearzones (hazard-free areas along roadways) increase safety. However, systematic analysis indicates that crash rates actually decline with more street trees, apparently because trees encourage slower and more cautious driving.

Active travel (walking, bicycling, and their variants) have much higher per-mile traffic casualty rates than transit and automobile travel — so the reductionist analysis suggests that shifts from non-motorized to motorized modes would increase crashes. In practice, per capita traffic casualties tend to decline as active travel increases in a community, an effect called safety in numbers. This occurs because active travel imposes less risk on other road users, pedestrians and bicyclists travel fewer annual miles than motorists, which reduces their exposure, and drivers become more cautious in areas with more active travel.

Similarly, wide, grade-separated highways tend to have lower crash rates per vehicle-mile than surface streets. The reductionist analysis assumes that communities become safer with more freeways, but this is not the case, as illustrated below. Traffic death rates actually increase with per capita freeway-miles, apparently due to the additional vehicle travel they induce, including increases in surface street vehicle-miles.

Traffic Deaths Vs. Freeway Miles Per Capita

Organizations such as the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety assume that since smaller vehicle occupants are more likely to be injured in crashes with larger vehicles, driving a larger vehicle increases safety. If this were true, crash casualties should have declined as vehicle size increased in recent decades, as illustrated below, but this did not occur. Systematic analysis investigates whether larger vehicles encourage drivers to take more risks, whether they impose more injuries on other road users (yes and yes), and how vehicle size affects total crash casualties.

Cars Versus Light Truck Travel

Another problem with conventional traffic engineering is the often-applied but seldom-examined assumption that our primary goal is to maximize traffic speeds. This is embedded in performance indicators such as roadway level of service and hours of congestion delay; in the way that transportation funds are allocated (lots for high-speed highways, less for public transit, and very little for sidewalks and bikeways); and by the tendency to ignore induced vehicle travel. Such analysis exaggerates the benefits and underestimates the total costs of roadway expansions. As a result of these practices transportation agencies favor faster modes over slower but more affordable, safer and healthier modes; speed over safety, affordability, and equity in roadway design; and sprawl over compact development. Unintentionally, these practices tend to increase crashes.

Don’t blame engineers alone. Many of these practices are established by policymakers who define agency priorities, create funding structures, and legislate zoning codes and parking minimums, but traffic engineers are involved in developing and applying these policies. To their credit, many engineers support multimodal planning, but most could do more. In particular, we could do a better job of showing the large safety benefits provided by multimodal transportation planning, transportation demand management and Smart Growth development policies.

Better solutions

More systematic risk analysis expands the range of safety strategies that can be used to increase safety. It recognizes that multimodal planning, TDM, and Smart Growth can significantly reduce per capita traffic injuries and deaths while also providing other economic, social, and environmental benefits (increasing affordability and equity, reducing road and parking facility costs, creating more livable communities, and reducing pollution emissions). Conventional traffic safety strategies, such as seat-belt encouragement and impaired driving discouragement, have largely reached their potential; new strategies are needed to achieve more safety gains.

Conventional |

New |

|

|

More comprehensive analysis expands the range of traffic safety strategies to include multimodal planning, TDM and Smart Growth development policies. These new strategies can save more lives and provide more total benefits than conventional traffic safety strategies.

Conventional traffic safety strategies tend to be programmatic — they involve a special intervention just for safety’s sake. Newer strategies tend to be structural – they change the way communities plan and fund transportation systems so people drive less, at lower speeds, and rely more on non-auto modes.

Many of these strategies are complementary. For example, safe driving campaigns become more effective, equitable, and politically acceptable if implemented in conjunction with multimodal planning and Smart Growth development policies so young men, frail seniors, and drinkers have convenient and affordable alternatives to driving.

Conclusions

This analysis shows that the U.S. has failed to achieve traffic safety goals. Despite large investments in traffic safety programs, U.S. crash rates increased significantly in recent years and are now much higher than in most peer countries. These undesirable outcomes can be partly attributed to common traffic engineering practices that increase traffic speeds and total vehicle travel, and reduce the quality of non-auto modes.

Traffic engineers can increase total safety by applying more systematic risk analysis which considers indirect and well as direct effects, such as the additional risk that larger vehicles impose on occupants of smaller vehicles, the additional crashes that result from roadway expansions that induced vehicle travel, and the reductions in total traffic casualties that result from vehicle travel reductions and Smart Growth development policies.

Professor Wes Marshall’s new book, Killed by a Traffic Engineer, challenges many common traffic engineering practices. It highlights the importance of exposure -- total motor vehicle traffic volumes and speeds -- as a risk factor. This book describes many examples of pseudoscience in traffic engineering which overlook the risks of higher traffic speeds, increased vehicle traffic and sprawl, resulting in planning decisions that unintentionally encourage more and faster driving, resulting in more total traffic casualties.

Despite the book's controversy, Marshall has a positive message overall: communities can become much safer and achieve other goals with roadway design and planning that prioritize accessibility over mobility, and safety over speed.

For more information

Buff Brown (2024), The Barrier of the City Engineer (Rap), Youtube.

Ralph Buehler and John Pucher (2021), “The Growing Gap in Pedestrian and Cyclist Fatality Rates Between the United States and the United Kingdom, Germany, Denmark, and the Netherlands, 1990–2018,” Transport Reviews, Vo. 41:1, pp. 48-72 (DOI: 10.1080/01441647.2020.1823521).

Reid Ewing, Richard A. Schieber and Charles V. Zegeer (2003), “Urban Sprawl as a Risk Factor in Motor Vehicle Occupant and Pedestrian Fatalities,” American Journal of Public Health.

Nicholas N. Ferenchak and Wesley E. Marshall (2024), “Traffic Safety for All Road Users: A Paired Comparison Study of Small & Mid-Sized U.S. Cities With High/Low Bicycling Rates," Journal of Cycling and Micromobility Research (doi.org/10.1016/j.jcmr.2024.100010).

Norman W. Garrick and Wesley Marshall (2011), “Does Street Network Design Affect Traffic Safety?” Accident Analysis and Prevention, Vo. 43/3, pp. 769-81, (DOI: 10.1016/j.aap.2010.10.024).

Todd Litman (2022), “Driving as a Risk Factor: A New Paradigm for Vision Zero,” Vision Zero Cities Journal.

Todd Litman (2024), “A New Traffic Safety Paradigm,” Victoria Transport Policy Institute.

Wesley E. Marshall (2018), “Understanding International Road Safety Disparities: Why is Australia So Much Safer than the US?,” Accident Analysis & Prevention (doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2017.11.031).

Wesley E. Marshall and Norman W. Garrick (2012), "Community Design and How Much We Drive,” Journal of Transport and Land Use (doi: 10.5198/jtlu.v5i2.301).

Wesley E. Marshall, Nick Ferenchak and Bruce Janson (2018), Why are Bike-Friendly Cities Safer for All Road Users?, Mountain Plains Consortium.

Wesley E. Marshall and Nicholas N. Ferenchak (2019), “Why Cities with High Bicycling Rates are Safer for All Road Users,” Journal of Transport & Health (doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2019.03.004).

Wesley E. Marshall P.E., Nicholas Coppola and Yaneev Golombek (2018), “Urban Clear Zones, Street Trees, and Road Safety,” Research in Transportation Business & Management (doi.org/10.1016/j.rtbm.2018.09.003).

Murray May, Paul J. Tranter and James R. Warn (2011), “Progressing Road Safety through Deep Change and Transformational Leadership,” Journal of Transport Geography (doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2011.07.002).

Jiho Yeo, Sungjin Park and Kitae Jang (2015), “Effects of Urban Sprawl and Vehicle Miles Traveled on Traffic Fatalities,” Traffic Injury Prevention (doi.org/10.1080/15389588.2014.948616W).

David Zipper (2024), “A Traffic Engineer Hits Back at His Profession. A new book argues that road design, not driver error, is largely responsible for the surge in US traffic deaths among pedestrians and bicyclists.” Bloomberg News.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Restaurant Patios Were a Pandemic Win — Why Were They so Hard to Keep?

Social distancing requirements and changes in travel patterns prompted cities to pilot new uses for street and sidewalk space. Then it got complicated.

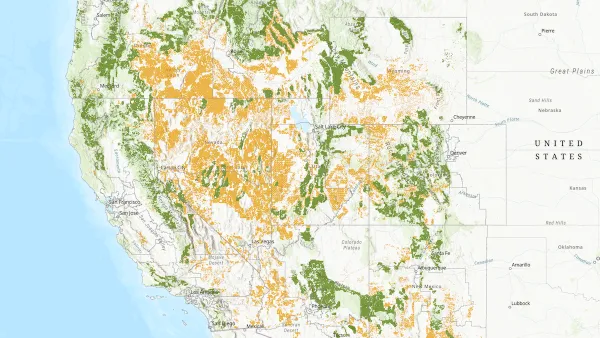

Map: Where Senate Republicans Want to Sell Your Public Lands

For public land advocates, the Senate Republicans’ proposal to sell millions of acres of public land in the West is “the biggest fight of their careers.”

Maui's Vacation Rental Debate Turns Ugly

Verbal attacks, misinformation campaigns and fistfights plague a high-stakes debate to convert thousands of vacation rentals into long-term housing.

San Francisco Suspends Traffic Calming Amidst Record Deaths

Citing “a challenging fiscal landscape,” the city will cease the program on the heels of 42 traffic deaths, including 24 pedestrians.

California Homeless Arrests, Citations Spike After Ruling

An investigation reveals that anti-homeless actions increased up to 500% after Grants Pass v. Johnson — even in cities claiming no policy change.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Heyer Gruel & Associates PA

JM Goldson LLC

Custer County Colorado

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

Transportation Research & Education Center (TREC) at Portland State University

Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Claremont

Municipality of Princeton (NJ)