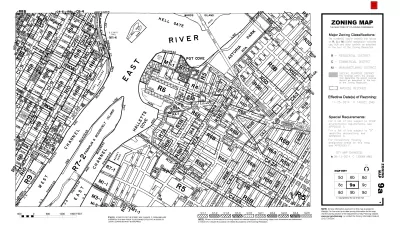

In addition to attacking zoning laws' limitations on housing, Gray argues that zoning fails to limit nuisances.

The major purpose of Nolan Gray's new book, Arbitrary Lines, is to show that by limiting housing construction, zoning increases rents by limiting housing supply, accelerates suburban sprawl by reducing density and pricing Americans out of walkable areas, and slows economic growth by making it expensive for Americans to move to prosperous areas. On each count, Gray makes a persuasive (to me) case.

While advocates of the status quo claim that developers run cities, Gray points out how difficult it is to build housing. For example, he writes that New York City built fewer new units during the 2010s than it did in the 1930s, and that apartments are forbidden on most urban land.

Because this is a popular book rather than a scholarly one, Gray doesn't fully address counterarguments. (If you want a scholarly treatment of pro-zoning counterarguments, you might wish to read some of my own work or Vicki Been's work on “supply skepticism.”)

In addition to covering this well-trodden ground, Gray covers some issues I have not thought about so much, most notably the historical origins of zoning, Japan's more successful zoning rules, and its failure to control nuisance land uses.

As to the former, the conventional justification of zoning is that it protects residential neighborhoods from smelly, polluting factories and other nuisance land uses. But Gray suggests that even in the 1910s, when the first zoning codes were created, some zoning advocates sought to exclude the poor and nonwhites from rich areas.

Gray notes that while housing costs have skyrocketed in other countries, Tokyo remains “remarkably affordable.” Why? Japan's national government limits local governments to 12 zoning districts; even though cities can choose between them, they cannot make the law more complex by adding additional districts, thus preventing cities "from developing boutique districts implicitly designed to block certain types of development." In addition, no zoning district is allowed to completely exclude apartments (unlike in the United States). Although some Japanese zones have height limits, others merely require taller buildings to step back every few stories in order to protect sunlight, much like New York's Empire State Building.

The traditional progressive argument for zoning is that it limits pollution from factories and other nuisances. Gray notes that zoning has not been particularly successful in limiting pollution for three reasons. First, areas near zoning boundaries are still subject to pollution: for example, if street 1 is zoned for smelly factories and streets 2-20 are zoned for housing, streets 2 and 3 might be close enough to the factory to suffer from pollution. Second, even a permitted activity can be obnoxious: for example, a cell phone store can blast music out into the street, turning an ordinarily innocuous activity into a nuisance. Third, cities often use zoning to dump noxious activities into low-income areas, ensuring that the poor don't get much protection from pollution. Thus, zoning is both underinclusive and overinclusive.

As a first step, Gray suggests a variety of incremental reforms; his thoughts on this issue were recently published on Planetizen. But Gray would prefer a more aggressive program. He suggests that zoning in its current form should be abolished; however, he is hardly a pure libertarian.

As an alternative to the status quo, Gray favors activity-by-activity regulations such as noise ordinances and laws limiting universally unpopular or unsafe activities such as smelly industries and floodplain development. To stop segregation and displacement, Gray favors expanded subsidies for housing vouchers and community land trusts. In addition, Gray suggests that neighborhoods should be allowed to voluntarily opt in to stricter rules by adopting restrictive covenants without the unanimous support of property owners. (It seems to me that this would allow some of the problems of the status quo to reappear, and is thus less than ideal).

Finally, Gray suggests that urban planners themselves would benefit from widespread deregulation. Currently, planners waste significant amounts of time refereeing fights between developers and neighborhood activists. But in a post-zoning system, developers could focus on shaping the physical form of the city through street design and the design of other public spaces.

Trump Administration Could Effectively End Housing Voucher Program

Federal officials are eyeing major cuts to the Section 8 program that helps millions of low-income households pay rent.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Ken Jennings Launches Transit Web Series

The Jeopardy champ wants you to ride public transit.

California Invests Additional $5M in Electric School Buses

The state wants to electrify all of its school bus fleets by 2035.

Austin Launches $2M Homelessness Prevention Fund

A new grant program from the city’s Homeless Strategy Office will fund rental assistance and supportive services.

Alabama School Forestry Initiative Brings Trees to Schoolyards

Trees can improve physical and mental health for students and commnity members.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Ada County Highway District

Clanton & Associates, Inc.

Jessamine County Fiscal Court

Institute for Housing and Urban Development Studies (IHS)

City of Grandview

Harvard GSD Executive Education

Toledo-Lucas County Plan Commissions

Salt Lake City

NYU Wagner Graduate School of Public Service