Many people assume that infectious disease risks make public transport dangerous and automobile travel safe, but this is generally untrue. Other factors have more effect on pandemic risk.

The following is an excerpt from my new report, "Pandemic-Resilient Community Planning: Practical Ways to Help Communities Prepare for, Respond to, and Recover from Pandemics and Other Economic, Social and Environmental Shocks." It follows my recent column, "Lessons from Pandemics: Comparing Urban and Rural Risks." Please let me know what you think of this analysis, and if there are more ways that planners can help communities prepare for life's uncertainties.

There is considerable debate concerning the role that various transportation modes play in spreading infectious diseases, and how their contagion risks to users compare. Many people assume that infectious disease risks make public transit dangerous and automobile travel safe, but good research suggests that this is generally untrue. All forms of travel present contagion risks, many factors affect these risks, and smart policies can reduce these risks.

Both long-distance and local travel present infection risks: long-distance travel can introduce diseases into a community and local travel can disperse it. Transport hubs and corridors, such as airports and highways, are often gateways to diseases. All shared vehicles present risks: buses, trains and airplanes can have crowded vehicles and stations, while automobiles used for taxis, ridehailing, or carrying family and friends have confined spaces and numerous touch services (handles, arm rests and seats).

These risks are difficult to compare; for example, it is uncertain whether total contagion risk is lower if 1,000 non-drivers travel on 100 buses with 10 average passengers, 500 taxi/ridehail vehicles with a driver and two average passengers, or 1,000 private cars with a driver and one passenger, since each presents unique risks. If motorists feel safe and so average 10 weekly vehicle trips, including some with passengers, while transit-dependent people feel unsafe and so only make two weekly transit trips, walk or bicycle for most errands, and practice careful hygiene, the motorists may spread more contagion than transit users even if their per trip risks are higher.

This suggests that to reduce risks travellers should minimize all forms of shared vehicle travel. This can severely constrain the out-of-home activities of non-drivers in automobile-dependent areas. Commuters who don’t drive may be unable to work, and adolescents and seniors will be deprived of independence. Even urgent rides, such as healthcare access, can be difficult and costly in sprawled areas where taxi and ridehailing services are limited and travel distances are long. Intercity vehicle travel may also be inconvenient, due to limited traveler services.

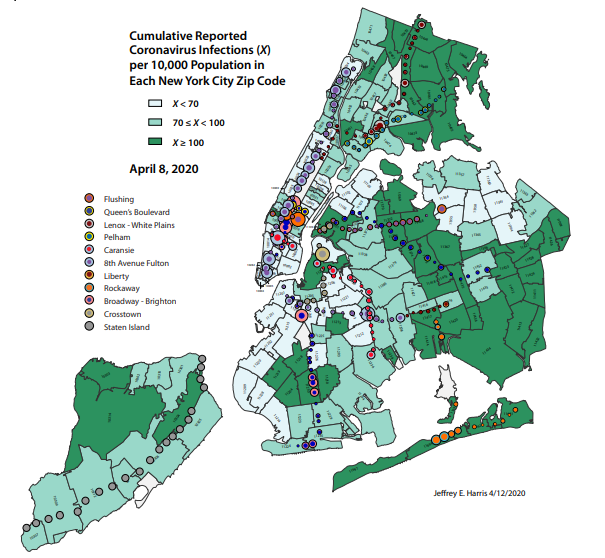

Public transport can present special risks. A recent paper by Jeffrey E. Harris, The Subways Seeded the Massive Coronavirus Epidemic in New York City, claimed to demonstrate that subways were the major cause of COVID-19 dispersion in New York City, based on maps showing reported cases concentrated along subway lines, and declines in new cases following late-March ridership declines, but critics point out that infection rates are actually higher in more automobile-oriented suburban areas than in transit-oriented areas, and many other contagion-control policies were implemented in late March which can explain the decline in new infections (Furth 2020; Gordon 2020; Grabar 2020; Levy 2020; Winkelman 2020).

New York City Infection Rates (Harris 2020)

Harris claimed that this map demonstrates a correlation between subway ridership and COVID-19 infections, but critics point out that infection rates were much higher in the more automobile-oriented outer neighborhoods of Staten Island and the Bronx, and low in the densest, most transit-oriented neighborhoods in Manhattan and western Brooklyn.

For critical analysis of Harris' study see:

Automobiles Seeded the Massive Coronavirus Epidemic in New York City (Furth 2020)

It’s Easy, But Wrong, to Blame the Subway for the Coronavirus Pandemic (Gordon 2020)

The Subway is Probably not Why New York is a Disaster Zone (Levy 2020)

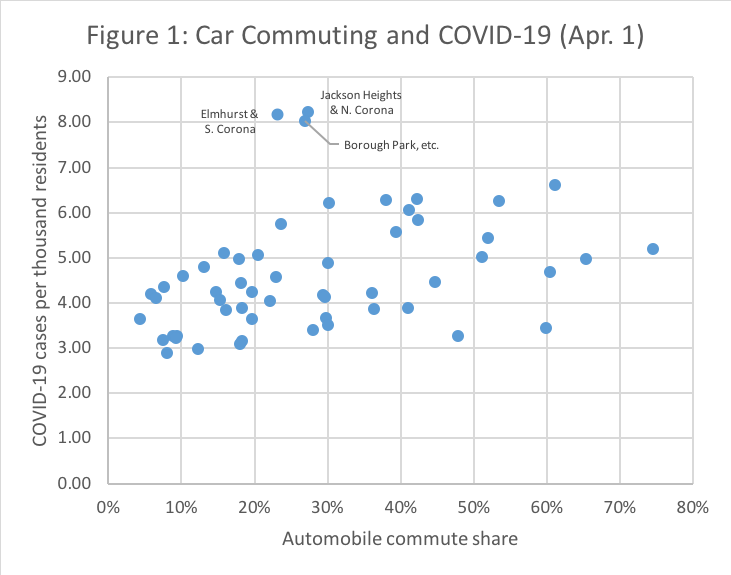

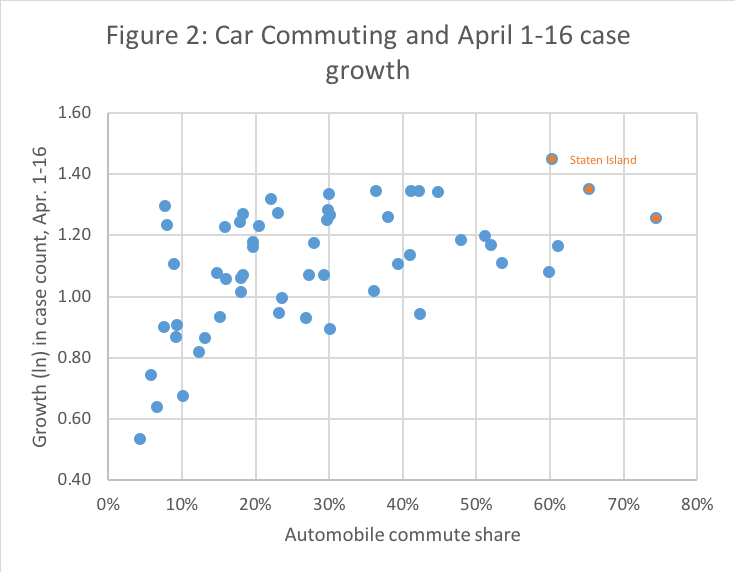

COVID-19 Infection Rates Versus Auto Commute Mode Share (Furth 2020)

Aron Furth’s study, "Automobiles Seeded the Massive Coronavirus Epidemic in New York City," shows statistically strong positive correlations between automobile commute mode shares and both COVID-19 infection rates (figure above) and April 1-16 infection growth rates (figure below), plus strong negative correlations between both subway and other transit commute mode shares and infection rates.

Furth notes two ways that motorists are likely to spread disease more than subway users. Car users tend to travel farther, and reduce their trip-making less than subway-dependent people because driving seems safer than transit travel. For example, if a grocery store in a transit-oriented area becomes contagious the exposure is concentrated to a smaller pool of local residents, but infected motorists are likely to drive to a wider range of destinations, which exposes a much larger pool of people.

This is not to deny that public transit can spread infectious diseases, particularly crowded subways, due to heavy passenger volumes and poor ventilation, but this research suggests that many other factors have far more effect on individual and community infection rates, so well-managed public transit travel is likely to be safer than poorly-managed automobile travel, including all the chauffeured vehicle travel required in sprawled, automobile-dependent communities.

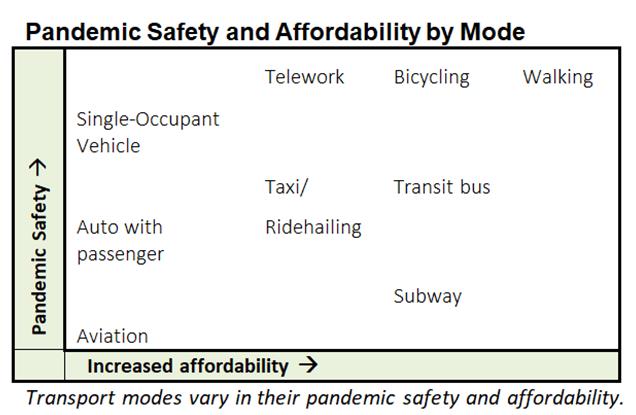

Transit risks can be reduced by limiting crowding, appropriate cleaning and sanitizing, employee and passenger hygiene, operator protection (Fletcher, et al. 2014), and operational improvements that reduce delay (TransitCenter 2020). Taxi, ridehailing and motorists carrying passengers can reduce risks by limiting crowding, cleaning, sanitizing and hygiene. Taxi and ridehailing companies can offer sick leave so drivers are less likely to work when they may be contagious. Delivery services reduce but do not eliminate risk since couriers handle many people’s goods. Walking, bicycling and telework are generally the safest and most affordable travel modes, making walkable urban neighborhoods resilient, particularly if they are designed for minimal crowding and sociable distancing.

Transportation Risks and Solutions

Risks |

Solutions |

|

Long-distance travel |

Limit mobility and require quarantines, particularly from higher-risk areas. |

|

Private vehicle travel |

Avoid carrying passengers, clean touch surfaces, encourage hygiene. |

|

Taxi and ridehailing |

Limit crowding, clean touch surfaces, encourage hygiene, protect operators. |

|

Public transit vehicles |

Limit crowding, clean touch surfaces, encourage hygiene, protect operators. |

|

Terminals |

Limit crowding, clean touch surfaces, encourage hygiene, protect employees. |

|

Walking and bicycling |

Encourage distancing. Limit automobile traffic and open streets to active modes. |

|

Create neighborhoods with convenient walking and bicycling access. |

Travel activities impose various risks which can be reduced.

Contagion risk is not the only planning issue to consider for pandemic-resilient community planning. This pandemic is causing large unemployment and business losses that will reduce many household’s incomes. Although stimulus funds, unemployment insurance, and bill deferment policies provide some relief, many households will need additional short- and long-term solutions. Although affordability concerns often focus on high housing costs, many households also face excessive motor vehicle cost burdens, including occasional large unexpected expenses from mechanical failures and crashes. Many moderate-income households have difficulty making vehicle loan, insurance or repair payments and will need affordable mobility options. As a result, affordability will be an important transportation planning objective in the future.

The figure below illustrates my estimate of the pandemic safety and affordability of various transport modes. This suggests that walking and bicycling are the safest and most affordable travel options, which means that walkable neighborhoods are the most pandemic-resilient community type, as discussed in my recent column, "Lessons from Pandemics: Comparing Urban and Rural Risks."

Below are local policies that can increase affordability:

- Implement eviction protection, rent moratoriums and deferrals, plus subsidies for at risk households.

- Increase allowable densities and building heights, and allow compact, missing middle housing types (secondary suites, multi-plexes, townhouses and low-rise apartments) in walkable urban neighborhoods, particularly for corner or larger lots, adjacent to parks, or on busier streets, since these locations minimize negative impact on neighbours.

- Reduce development fees, approval requirements and inclusivity mandates for moderate-priced ($200,000-400,000 per unit) infill housing, since these are the projects we most need.

- Reduce or eliminate parking minimums and favor unbundling (parking rented separately from housing units) so car-free households are not forced to pay for expensive parking facilities they do not need.

- Allow higher densities and building heights in exchange for more affordable units. Minimum target densities can be applied in accessible locations, for example, at least three stories along minor arterials and four stories along major arterials.

- Improve affordable housing design. Municipal governments can support design workshops and contests to encourage better design. The Affordable Housing Design Advisor, the Missing Middle Website, and Portland’s Infill Design Project are examples of affordable housing design resources.

- Improve active transport (walking and bicycling) and micro-mobility (electric scooters and bicycles) through improved sidewalks, crosswalks, bike lanes, complete streets policies, traffic calming and streetscaping.

- Improve public transport services so vehicles and stations are less crowded, cleaner, better ventilated and less delayed, through better design, increased cleaning, dedicated bus lanes, all-door boarding, driver protection, and automated fare payments system, actions that improve convenience and comfort as well as reducing disease risks.

- Implement Transportation Demand Management (TDM), which includes various policies and programs that encourage more efficient travel behavior. Local and regional governments can implement TDM strategies and require large employers to have Commute Trip Reduction programs.

- Support development of walkable urban villages along frequent public transit corridors (also called Transit Oriented Development or TOD) to create neighborhoods where residents and workers can easily access common services and activities without a car.

Will this pandemic cause people to abandon public transit? Probably not. Perhaps the most relevant example is experience after the September 11th terrorist attack, and various public transit terrorist attacks. At the time, many people claimed that these events would end urbanization and public transit demand. Cities and transit agencies responded with increased security and public education. Both urbanization and transit ridership soon returned to previous growth levels. Although terrorist attacks lead some people to dread (i.e., have irrational fear) cities and transit travel, they are, in fact, generally safer and healthier overall than suburban living and automobile travel.

During a major pandemic it may be rational to restrict public transit travel, but over the long run, total deaths and illnesses are likely to increase if exaggerated pandemic fear leads to long-term shifts from cities to automobile-dependent suburbs, or from public transit to automobile travel (Litman 2005).

Information Resources

CNT (2020), Urban Opportunity Agenda, Center for Neighborhood Technology.

ITE (2020), COVID-19 Resources, Institute of Transportation Engineers.

Polis (2020), COVID-19: Keeping Things Moving, Cities and Regions for Transport Innovation.

SLOCAT (2020), COVID-19 and the Sustainable Transport Community, Sustainable Low Carbon Transport Partnership.

Transit Center (2020), How Transit Agencies Are Responding to the COVID-19 Public Health Threat.

TUMI (2020), The COVID-19 Outbreak and Implications to Sustainable Urban Mobility – Some Observations, Transformative Urban Mobility Initiative.

UITP (2020), Management of COVID-19 Guidelines for Public Transport Operators, Union Internationale des Transports Publics (International Association of Public Transport).

Maui's Vacation Rental Debate Turns Ugly

Verbal attacks, misinformation campaigns and fistfights plague a high-stakes debate to convert thousands of vacation rentals into long-term housing.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Chicago’s Ghost Rails

Just beneath the surface of the modern city lie the remnants of its expansive early 20th-century streetcar system.

Bend, Oregon Zoning Reforms Prioritize Small-Scale Housing

The city altered its zoning code to allow multi-family housing and eliminated parking mandates citywide.

Amtrak Cutting Jobs, Funding to High-Speed Rail

The agency plans to cut 10 percent of its workforce and has confirmed it will not fund new high-speed rail projects.

LA Denies Basic Services to Unhoused Residents

The city has repeatedly failed to respond to requests for trash pickup at encampment sites, and eliminated a program that provided mobile showers and toilets.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

planning NEXT

Appalachian Highlands Housing Partners

Mpact (founded as Rail~Volution)

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

City of Portland

City of Laramie