Steven T. Moga guest blogs about a new article in the Journal of Planning Education and Research.

Guest Blogger: Steven T. Moga of Smith College.

Six years ago, I was trying to uncover how a neighborhood in Columbus, Ohio named “The Bottoms” had been originally zoned. I could not find the maps in the public library or, seemingly, anywhere. But, then, after several phone calls, and the hint of recognition by a longtime planner, I received an invitation, made a quick drive across town, wound my way through a cubicle warren, and, finally… success! There they were. Undated, tattered, pieced together with formerly-transparent-turned-yellowish-brown adhesive tape, and shelved away in flat files. The thrill of discovering these amazing lost artifacts of the urban past led me to celebrate—and then pause. What, I wondered, might be the value, if any, in these old, seemingly forgotten, and definitely arcane maps? This question started a strange and fascinating research journey that ultimately led to my recent article in the Journal of Planning Education and Research.

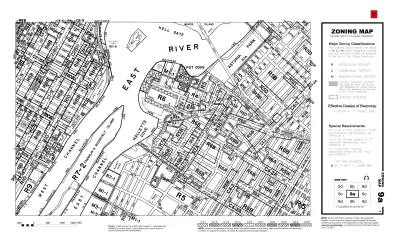

I became fascinated by these old maps: as laws in the form of pictures, as administrative tools, as physical artifacts marked by wear-and-tear, and as early 20th century inventions created to apply ordinance texts to the real, physical territories of existing cities. I began to see them as visual abstractions of the American city: maps that obscured patterns of urban form, but also potentially revealed something about how Americans have viewed the city and the planning process. I decided to investigate by seeking out more maps, more examples from the 1920s and 1930s.

In 2012, I posted an online query to the H-Urban listserve. The response was amazing; planners, urban historians, librarians, and archivists wrote back, describing where to find early zoning maps for cities across the United States. In fact, many of these historic maps have been digitized and can be accessed online. I examined dozens of zoning maps, from Seattle, Cleveland, St. Paul, Boston, Bridgeport, Nashville, New York, Los Angeles, and other U.S. cities. Immediately, the abstract visual qualities of the early black-and-white maps intrigued me: polka dots, diagonal stripes, and checkerboard shading patters arrayed across street networks in a crazy quilt. I realized that I had the raw material for a unique take on one of American planning's most researched and debated topics: zoning. The map offered a new angle of approach.

Then I reviewed publications from the historic period and the vast secondary literature. Perhaps most striking in the historical research was the optimism of zoning's proponents. Ordinance and map were imagined to bring order to the city. By discovering the districts of the existing city and consulting with property owners, the proper boundaries and the appropriate regulatory classifications would be determined and set down on maps. But what resulted instead tended to be a visual jumble: a visually fragmented and complex illustration that was difficult to parse. My paper’s findings emerged from visual analysis of these early zoning maps.

First, looking at the oldest zoning maps highlighted to me their character as temporal compromises. That is, the maps represent neither the existing condition of the American city of the 1920s nor a vision for an ideal future. They were not future-oriented plans, but rather schema for orderly future real estate development that grew out of present land uses and forms, but didn’t strictly adhere to it or seek to continue traditional or historical patterns.

Second, boringness of appearance helped obscure the map's origins. Racist intent, profit motives, class segregation, and other motives could hide behind a visual device that quickly began to look normal, rational, apolitical, official, and final.

Third, as a visual intermediary in the development process, the map could take power away from both elected officials and bureaucrats, but its content wasn't so fixed that it couldn't be modified. Obscured origins and visual character abetted speculative activity without raising a fuss. The entire map need not be replaced or a new mapping schema invented when interested parties sought a zoning change. The basic form of the map proved remarkably durable.

This project has benefited enormously from the suggestions of people interested in planning and zoning. My aim has been to continue the conversation and share what I have learned. Your comments are welcome.

Open Access Until November 26, 2016

Moga, ST., 2016. "The Zoning Map and American City Form." Journal of Planning Education and Research

What ‘The Brutalist’ Teaches Us About Modern Cities

How architecture and urban landscapes reflect the trauma and dysfunction of the post-war experience.

San Diego to Rescind Multi-Unit ADU Rule

The city wants to close a loophole that allowed developers to build apartment buildings on single-family lots as ADUs.

The VW Bus is Back — Now as an Electric Minivan

Volkswagen’s ID. Buzz reimagines its iconic Bus as a fully electric minivan, blending retro design with modern technology, a 231-mile range, and practical versatility to offer a stylish yet functional EV for the future.

Study: Walkability Can Help Reduce Dementia Risk

Walkable neighborhoods offer natural opportunities to stay active and engaged with friends and neighbors, increasing residents’ chances of remaining mentally and physically healthy longer.

Empower LA: The LA2050 Grants Challenge

The 2025 LA2050 Grants Challenge invites organizations to become outreach partners and help mobilize Angelenos to vote on how $1 million in grants will be allocated to address key local issues like homelessness, income inequality, and park access.

Take a Walk: Why Step Count Is the Most Valuable Fitness Metric

Step count remains the most valuable fitness metric for longevity and well-being, offering a simple yet powerful way to track daily movement, reduce health risks, and promote active lifestyles without reliance on complex data or technology.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

City of Edmonds

City of Albany

Harvard GSD Executive Education

UCLA Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies

Mpact (formerly Rail~Volution)

City of Piedmont, CA

Great Falls Development Authority, Inc.

HUDs Office of Policy Development and Research