Tesla has just disclosed the first fatal crash of a driver using its "Autopilot" system. Tesla should be concerned about the question of who's liable, and we should all be concerned about the wider consequences of this tragic event.

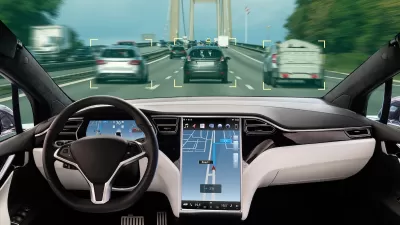

Tesla Motors disclosed last week the first fatality of a customer using its 'Autopilot' system of partial self-driving automotive technology. This is thought to be the first death attributable to a Highly-Automated Car, so is something of a watershed moment: the Age of Innocence is over. The facts are murky at present and will emerge in due course. Initial reports are that the driver may have been watching a (Harry Potter) video at the time of the crash, in flagrant violation of the agreement between him and Tesla. Tesla maintains that "you need to maintain control and responsibility for your vehicle while using [Autopilot]", and has given no indication yet of whether or not it believes that it is liable in any way for the crash.

This crash is very sad news for the deceased's family, with potentially much wider ramifications as well.

Last month my team and I released a new (long: 20K words) Working Paper on the liability issues raised by Automated Cars, and how this will constrain how they drive. I want to therefore share initial thoughts on this incident, starting with specific reasons for Tesla to be concerned, and concluding with broader reasons for the rest of us to also pay attention:

Three reasons that Tesla should be concerned

- The reaction time of Automated Cars' control systems in pre-crash situations are in principle much faster than human drivers' reaction times. This might mean that the system's designer (Tesla) could be vulnerable under the 'Last Clear Chance' legal doctrine, because Autopilot's superior reaction time might be interpreted to mean that it had the Last Clear Chance (i.e., later than the human drivers of both vehicles involved) to avoid the crash. The 'Last Clear Chance' doctrine means that a human driver may bear some negligence in a crash even if they were not violating the Rules of the Road, if they had the 'Last Clear Chance' to avoid the crash.

- Even car passengers may have a 'Duty to Remonstrate' (i.e., raise objections) when a car driver is driving badly, otherwise they might be found partly negligent in the event of a crash. Is the relationship between Tesla's Autopilot System and the driver using it not a stronger one than the relationship between a car driver and a passenger? It would seem to be a stronger relationship in multiple, demonstrable ways.

- Courts have also held that car passengers may be partially liable under the 'Joint Enterprise' doctrine, if "there is an understanding or an agreement in advance between the driver and the passenger that the passenger has a right to tell the driver how to drive the automobile" (see Siruta v. Siruta, 348 P.3d 549 (Kan. 2015), which discusses "[shared] negligence as a result of joint driving decisions"). While it's clear that the human driver of the Tesla was negligent, these legal doctrines emanating originally from the traditional car-driver/car-passenger relationship may provide precedent for joint negligence between a driver and system-designer that are both concurrently making driving decisions.

Three reasons for the rest of us to be concerned:

- Tesla has been less than forthright here, taking nearly two months to inform its customers and the general public (and its shareholders) of an incident that it must have realized would be of wide interest. It has not yet disclosed any remedy that it took in the interim to prevent a recurrence, such as, perhaps temporarily disabling or restricting the Autopilot system on its cars until the facts are established. This period of delay cannot be an oversight, and violates the fundamental crisis-management principle of getting bad news out quickly and fully. Though there is no way to know Tesla's logic for waiting to disclose, one uncharitable explanation could be that it was expecting to brush this under the carpet for commercial reasons (until the clumsy federal regulators loused it all up by not playing along). Designers of Automated Cars will not be able to maintain the public's trust if behavior of this sort becomes habitual; openness and transparency are basic requirements for an orderly rollout of the technology.

- It was a fundamental sensing failure (apparently the failure to distinguish a left-turning tractor trailer from background scenery) that prevented the Autopilot system from intervening to prevent the crash (or at least to mitigate it: no braking was performed by either human or Autopilot). Even if the vehicle's cameras had difficulty discerning the white side of the truck from the "brightly lit sky" (as Tesla reports), its radar system should in principle be able to identify the trailer in its path as a threat -- except that a flat metal surface such as the side of a tractor-trailer makes an excellent surface to, at certain angles, be nearly invisible to radar (i.e., stealthy). Finally, the Autopilot system which apparently first interpreted the trailer as an overhead sign should have been able to re-evaluate this assessment as it approached the truck. There also appear to have been a host of other contributing factors, which may include a limited sight distance between the two vehicles (due to topography). This sensing failure highlights that much basic Research & Development remains to be done; the technology is not "ready" yet. It also makes plain that while Automation will eliminate many of the 94% of crashes that are directly attributable to human error, we will need to contend with new crash scenarios caused by system failures.

- Automated Cars will probably make our roads safer overall—we expect this, but can’t yet be 100% sure. However, the tort system may well impose costs-per-crash on Automated Cars’ manufacturers that are much higher than costs-per-crashes of human drivers, which could reduce overall safety if this has a deterrence effect that inappropriately delays the rollout of the technology. Automated Cars will rigorously follow the rules laid out by their designers – and saying ‘sorry I didn't mean it’ won't be a viable option, because the behavior is programmed in, not a reaction to a ‘sudden emergency’ as with humans’ crashes. Designers of Automated Cars will have deep pockets, so will be also much more attractive targets for litigation than hapless human drivers, who have far fewer assets to pursue. Finally, the corporate designers of Automated Cars making deliberative choices will probably be seen by juries as less sympathetic than us hapless human drivers who might ‘make honest mistakes’ in the 'heat of the moment', and therefore juries might feel emboldened to impose larger awards for actual and punitive damages.

The risk is that we lose sight of the forest (overall safety benefits), owing to the trees (individually tragic incidents of which this is the first).

[An earlier version of this article was originally posted July 1st at: http://www.planetizen.com/node/63956]

Alabama: Trump Terminates Settlements for Black Communities Harmed By Raw Sewage

Trump deemed the landmark civil rights agreement “illegal DEI and environmental justice policy.”

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

The 120 Year Old Tiny Home Villages That Sheltered San Francisco’s Earthquake Refugees

More than a century ago, San Francisco mobilized to house thousands of residents displaced by the 1906 earthquake. Could their strategy offer a model for the present?

Indy Neighborhood Group Builds Temporary Multi-Use Path

Community members, aided in part by funding from the city, repurposed a vehicle lane to create a protected bike and pedestrian path for the summer season.

Congestion Pricing Drops Holland Tunnel Delays by 65 Percent

New York City’s contentious tolling program has yielded improved traffic and roughly $100 million in revenue for the MTA.

In Both Crashes and Crime, Public Transportation is Far Safer than Driving

Contrary to popular assumptions, public transportation has far lower crash and crime rates than automobile travel. For safer communities, improve and encourage transit travel.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Clanton & Associates, Inc.

Jessamine County Fiscal Court

Institute for Housing and Urban Development Studies (IHS)

City of Grandview

Harvard GSD Executive Education

Toledo-Lucas County Plan Commissions

Salt Lake City

NYU Wagner Graduate School of Public Service