Time is a limited and valuable resource. As much as possible, people should spend the precious hours of their lives in the most satisfying and productive possible ways. This has important implications for transportation planning, since most people spend a significant amount of time in transport, and travel time savings are often the greatest projected benefits of transport projects such as roadway and transit service improvements.

Time is a limited and valuable resource. As much as possible, people should spend the precious hours of their lives in the most satisfying and productive possible ways. This has important implications for transportation planning, since most people spend a significant amount of time in transport, and travel time savings are often the greatest projected benefits of transport projects such as roadway and transit service improvements.

In a recent Planetizen Blog, The Cost of Slow Travel, Steven Polzin presents the conventional travel time valuation perspective, which assumes that time spent traveling is wasted, so faster modes (such as driving) are inherently superior to slower modes (such as walking, cycling and public transit). He concludes, "One of the reasons the country and individuals have become more productive and the country has had growing gross domestic product over the past several decades is that we have been highly mobile and travel has gotten faster until recent years. Part of the reason for faster travel has been the shifting from slow to faster modes and facilities."

I respectfully disagree. My research on travel time valuation, published in my report Transportation Cost and Benefit Analysis, highlights some importance nuances in travel time valuation that conventional analysis ignores. This research indicates that:

-

Travel time costs are extremely variable. Under favorable conditions, slower modes have lower unit costs than driving. In some cases these time costs become negative; many people want to spend a certain amount of time each day walking and cycling.

-

When all costs are considered, slower modes are often more time-efficient overall than driving.

-

Because conventional transport planning fails to consider these factors, it tends to exaggerate the benefits of roadway expansion, and underestimate the value of improvements to alternative modes and smart growth policies. In other words, this is one way that conventional planning is biased in favor of mobility over accessibility, and automobile travel over alternative modes.

-

Increasing motorized travel and average travel speeds does not necessarily increase economic productivity. On the contrary, excessive automobile dependency reduces economic productivity. The most economically efficient transport system offers travelers a diverse range of accessibility options, with incentives to use the most efficient mode for each trip. This tends to result in relatively low automobile mode split and modest overall average travel speeds.

Here are more details about these issues:

Travel time costs are the product of the time spent traveling (measured as minutes or hours) multiplied by travel time unit costs (measured as cents per minute or dollars per hour). Travel time unit costs vary significantly depending on travel conditions and traveler preferences. For example, ten minutes spent relaxing on a comfortable bus or train imposes less cost than the same amount of time spent driving in congestion or standing on a crowded bus. Some people enjoy driving, but others prefer walking, cycling or riding public transit. Some forms of travel can provide additional productivity benefits: walking and cycling provide exercise, and passengers can spend their travel time working, play or resting.

As a result, under favorable conditions many people will prefer to walk, bicycle or use public transit travel, even if this takes somewhat more time, because they enjoy the activity, value the exercise, or find that mode more relaxing and productive. Although this increases minutes per trip, it reduces the cost per minute, and so minimizes total travel time costs.

However, conventional transport planning generally assigns the same travel time unit costs to all travel, comfortable or uncomfortable, healthy or unhealthy, productive or unproductive, restful or stressful. As a result, it recognizes the value of increasing travel speeds, for example, by expanding roadways to reduce congestion delays, but ignores the value to consumers of improving travel convenience and comfort, for example, by improving walking and cycling conditions, creating nicer transit stations, reducing transit crowding, and providing real time transit vehicle arrival information, although research indicates that travelers place a high value on such improvements and they can be used to increase transport system efficiency, for example, to induce mode shifts that reduce traffic congestion.

Contrary to conventional analysis, driving is not always the most time efficient or productive way to travel. For example, it is more efficient to spend 20 minutes a day walking or cycling for errands then to spend 10 minutes a day driving for errands, plus an extra 10 minutes driving to a gym in order to spend 20 minutes walking on a treadmill or riding a stationary bicycle. Similarly, the extra time spent on a transit vehicle can be used productively for resting, playing or working; it is not wasted.

Automobile travel often has low effective speeds (also called social speed), which refers to travel distance divided by the total time spent traveling, maintaining vehicles and working to pay transport expenses. For example, a motorist who spends an average of 80 daily minutes driving 30 miles, plus another 80 minutes earning money to pay for their vehicle, averages only 11.3 miles per hour. Many people would save time overall by relying more on slower but less costly modes and working fewer hours each week.

Extensive research indicates that people have a relatively constant travel time budget (most people devote 60-90 daily minutes to travel, regardless of travel speeds), so it is generally inaccurate to claim that increasing traffic speeds provide time savings. Instead, it allows people to travel farther within their time budget, for example, to live further from their worksite, and to shop at more distant stores. Although this provides benefit to users (the people who increase their mileage), it tends to increase external costs such as downstream congestion, parking costs, accidents, energy consumption and pollution emissions. Reducing delays for high value travel, such as freight, service and public transit vehicles, can provide significant economic productivity benefits, but this can be accomplished most efficiency with freight and HOV priority lanes or efficient road pricing. It is simply wrong to claim substantial long-term travel time savings and economic productivity gains from urban roadway expansion projects.

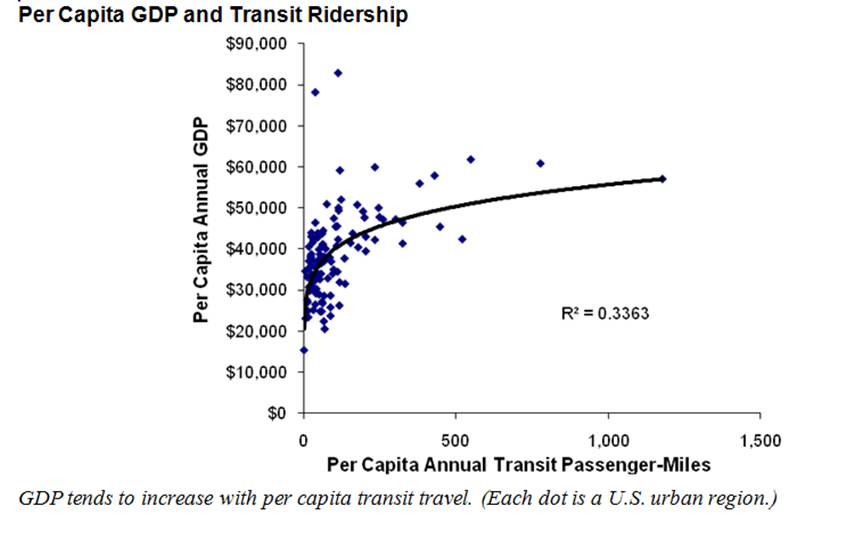

Contrary to Steven Polzin's assertion, in developed countries increased automobile travel does not increase economic productivity. On the contrary, beyond an optimal level, increased automobile travel tends to reduce economic productivity. This is illustrated by these two figures, which compare economic productivity and transport activity in U.S. cities. The first shows that per capita Gross Domestic Product (GDP) tends to decline with increased vehicle travel. The second shows that per capita GDP tends to increase with increased public transit ridership.

This occurs because, once the most important vehicle trips are served (for example, freight and business transport, emergency and service vehicles, and efficient public transit) the marginal economic benefits of increased automobile travel decline while their external costs (congestion, facility costs, accidents, fuel import costs, pollution emissions, sprawl) increase.

This has important implications for transport planning. It means that trasport project evaluation should give as much attention to the convenience and comfort of personal travel as to its speed, and that many of the resources currently devoted to increasing vehicle traffic speed could be more efficiently devoted to improving walking, cycling and public transit travel conditions. Such improvements respond to consumer demands and are often the most cost effective way to achieve mode shifts from driving to alternative modes, which increase overall transport system efficiency. For example, many residents would prefer to be able to walk or bike for local errands, rather than being forced to drive, but require better sidewalks, crosswalk and paths, and many workers would prefer to use public transit rather than drive for some of their commute trips, provided that bus stops and train stations were more attractive environments, and buses and trains were less crowded, cleaner, more secure, and offered amenities such as on-board wi-fi services. By shifting travel from automobile to alternative modes, this reduces external costs including traffic congestion, benefiting everybody, including motorists. Such improvements are cheap compared with the costs of continually expanding roadways with the intention of reducing delay and saving travel time.

For more information:

Todd Litman (2007), Build for Comfort, Not Just Speed: Valuing Service Quality Impacts In Transport Planning, VTPI (www.vtpi.org); at www.vtpi.org/quality.pdf.

Todd Litman (2009), "Travel Time Costs," Transportation Cost and Benefit Analysis, Victoria Transport Policy Institute (www.vtpi.org/tca/tca0502.pdf).

David Metz (2008), "The Myth of Travel Time Saving," Transport Reviews, Vol. 28, No. 3, pp. 321- 336; at http://pdfserve.informaworld.com/149983__910667966.pdf.

Nariida C. Smith, Daniel W. Veryard and Russell P. Kilvington (2009), Relative Costs And Benefits Of Modal Transport Solutions, Research Report 393, NZ Transport Agency (www.nzta.govt.nz); at www.nzta.govt.nz/resources/research/reports/393/docs/393.pdf.

Paul J. Tranter (2004), Effective Speeds: Car Costs are Slowing Us Down, University of New South Wales, for the Australian Greenhouse Office (www.climatechange.gov.au); at www.environment.gov.au/settlements/transport/publications/effectivespeeds.html.

What ‘The Brutalist’ Teaches Us About Modern Cities

How architecture and urban landscapes reflect the trauma and dysfunction of the post-war experience.

‘Complete Streets’ Webpage Deleted in Federal Purge

Basic resources and information on building bike lanes and sidewalks, formerly housed on the government’s Complete Streets website, are now gone.

The VW Bus is Back — Now as an Electric Minivan

Volkswagen’s ID. Buzz reimagines its iconic Bus as a fully electric minivan, blending retro design with modern technology, a 231-mile range, and practical versatility to offer a stylish yet functional EV for the future.

Healing Through Parks: Altadena’s Path to Recovery After the Eaton Fire

In the wake of the Eaton Fire, Altadena is uniting to restore Loma Alta Park, creating a renewed space for recreation, community gathering, and resilience.

San Diego to Rescind Multi-Unit ADU Rule

The city wants to close a loophole that allowed developers to build apartment buildings on single-family lots as ADUs.

Electric Vehicles for All? Study Finds Disparities in Access and Incentives

A new UCLA study finds that while California has made progress in electric vehicle adoption, disadvantaged communities remain underserved in EV incentives, ownership, and charging access, requiring targeted policy changes to advance equity.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

City of Albany

UCLA Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies

Mpact (formerly Rail~Volution)

Chaddick Institute at DePaul University

City of Piedmont, CA

Great Falls Development Authority, Inc.

HUDs Office of Policy Development and Research