More than two years years ago I chronicled my daily bicycle commute in Miami. The 8-mile trip was as representative of Miami's built and socio-cultural landscape as it was harrowing. While that city has surely made progress in the pas two years, I'd be lying if I didn't disclose that I partially moved to New York City because of the progress being made in designing livable streets infrastructure. Quite simply, it feels good to be in a city that "gets it."

More than two years years ago I chronicled my daily bicycle commute in Miami. The 8-mile trip was as representative of Miami's built and socio-cultural landscape as it was harrowing.

While that city has surely made progress in the pas two years, I'd be lying if I didn't disclose that I partially moved to New York City because of the progress being made in designing livable streets infrastructure. Quite simply, it feels good to be in a city that "gets it."

So, without further ado, I offer to you what could be the nation's best commute. (feel free to position your own commute as such in the comments section below)

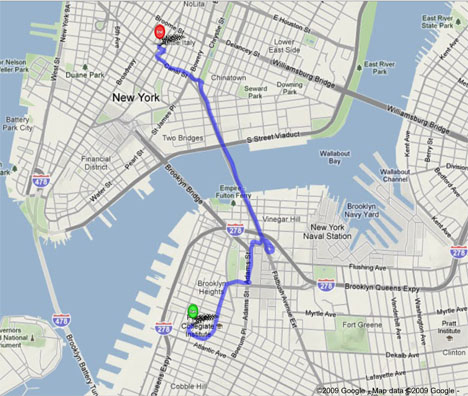

My 3-mile commute begins on Henry Street, in BrooklynHeights and ends on the border of SOHO and Chinatown in Manhanttan where I share office with the good folks at The Open Planning Project. Using an GPS iphone app, I can now trace my routes, snap photos, and upload them instantly to Google Maps, Twitter, or Facebook.

The Henry Street bicycle lane, designated in green, awaits me outside of the front door each morning. As you can see, the NYC Department of Transportation has enacted a policy to paint bicycle lanes green when they are placed directly next to a curb. It is assumed that this helps the lane become more visible to motorists and pedestrians. The well-marked lane also narrows the visual width of the vehicular lane, which, in theory, helps to slow cars down.

From Henry Street, I take a single-block jaunt east before moving several blocks north along the Clinton Street bicycle lane, which is a heavily traveled route for those bicylists traveling from points south towards the Brooklyn and Manhattan Bridges. Where Clinton meets Cadman Plaza West, a small "plaza" splits the vehicular and bicycle traffic. This aids cyclists in making a safe and direct transition across the four lane street to a two-way, protected bicycle lane on Tillary Street.

This is exactly the type of infrastructure that inspires interested, but concerned bicyclists to ride more frequently along streets once perceived to be too dangerous by the average person.

From here, the two-way, protected Lane provides a direct connection to the Brooklyn Bridge Shared Use Path, or to the Adams Street bicycle lane, which leads to the Manhattan Bridge via Sands Street. The connection is to undergo additional improvements by 2012.

I forgo the pedestrian packed Brooklyn Bridge in favor of the Manhattan Bridge bikeway. Adams Street offers a low traffic count street, but also features broken pavement and a standard--ho-hum--bicycle lane design that places the bicyclist in the door-zone. I frequently take the whole lane here to avoid the worst of these conditions. Fortunately, it's only a one-block section of my commute.

After turning right onto Sands Street, my commute takes me directly to the Manhattan Bridge bicycle ramp, which recently doubled in width to safely accommodate the growing number of bicyclists.

As an aside, the entrance to the Bridge from the north has also been dramatically improved (as seen above). This Streetfilms short depicts the completion of the so-called Budnick Bikeway--another two way, protected facility that ushers bicyclists to the foot of the bridge and the bicycle ramp.

The Manhattan Bridge offers a cantilevered two-way path for bicyclists over the East River, which offers sweeping views up the river and the Manhattan skyline.

Upon arriving in Manhattan, where the bridge entrance/exit has also been doubled for bicyclists, another two-way, protected cycle track offers safe passage for bicyclists heading to or from the bridge via Chrystie Street. Most bicyclists head north on Chrystie here, but my commute takes me west on Canal Street, which is the fastest and most direct route.

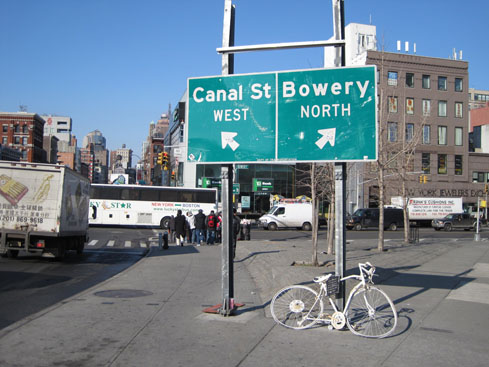

This final 7-block stretch is by far the most hectic, and perceivably unsafe part of my morning ride. As I exit the Manhattan Bridge bikeway, a contorted "ghost bike" reminds me that Canal Street--the epicenter of pedestrian and traffic thronged Chinatown--is not designed with users like me in mind. That being said, traffic moves slowly in the morning and I am able to reach my destination safely, and far faster than if I were in a car or bus. It also feels much safer than some of the 3-5 lane, one-way arterials I had to navigate in Miami.

As you can see here, under the leadership of Janette Sadik-Khan, New York City has made significant gains in the last two years in both perceived and real safety, and bicycle mode share. However, the city is a large and complex place where some neighborhoods are far more bikeable than others. To be sure, New York City still has a long way to go before it becomes comparable to some of the world's best cycling cities.

Nonetheless, the progressive work being done here is instructive, and at a scale and pace that surpasses all other American cities. And as my colleague, Michael Ronkin, is fond of saying, far more important than the design of any one bikeway is that the city is actually taking space away from cars to make more room for pedestrians and bicyclists.

With good fortune, I feel lucky to experience some of these improvements on my way to work.

What ‘The Brutalist’ Teaches Us About Modern Cities

How architecture and urban landscapes reflect the trauma and dysfunction of the post-war experience.

‘Complete Streets’ Webpage Deleted in Federal Purge

Basic resources and information on building bike lanes and sidewalks, formerly housed on the government’s Complete Streets website, are now gone.

The VW Bus is Back — Now as an Electric Minivan

Volkswagen’s ID. Buzz reimagines its iconic Bus as a fully electric minivan, blending retro design with modern technology, a 231-mile range, and practical versatility to offer a stylish yet functional EV for the future.

Healing Through Parks: Altadena’s Path to Recovery After the Eaton Fire

In the wake of the Eaton Fire, Altadena is uniting to restore Loma Alta Park, creating a renewed space for recreation, community gathering, and resilience.

San Diego to Rescind Multi-Unit ADU Rule

The city wants to close a loophole that allowed developers to build apartment buildings on single-family lots as ADUs.

Electric Vehicles for All? Study Finds Disparities in Access and Incentives

A new UCLA study finds that while California has made progress in electric vehicle adoption, disadvantaged communities remain underserved in EV incentives, ownership, and charging access, requiring targeted policy changes to advance equity.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

City of Albany

UCLA Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies

Mpact (formerly Rail~Volution)

Chaddick Institute at DePaul University

City of Piedmont, CA

Great Falls Development Authority, Inc.

HUDs Office of Policy Development and Research