Much of my work involves developing transportation demand management and smart growth policies which improve travel options (walking, cycling, public transit, carsharing, etc.), reform pricing and transport planning to encourage travelers to choose the most efficient mode for each trip, and create more accessible, multi-modal communities.

Much of my work involves developing transportation demand management and smart growth policies which improve travel options (walking, cycling, public transit, carsharing, etc.), reform pricing and transport planning to encourage travelers to choose the most efficient mode for each trip, and create more accessible, multi-modal communities. These policies can provide many benefits to travelers and society, including congestion reductions, road and parking facility cost savings, consumer savings and affordability, accident reductions, improved mobility for non-drivers, energy conservation, emission reductions, and improved public fitness and health. These ideas are gaining traction. For example, a number of recent studies have recommended transportation and land use management reforms as part of climate change emission reduction plans.

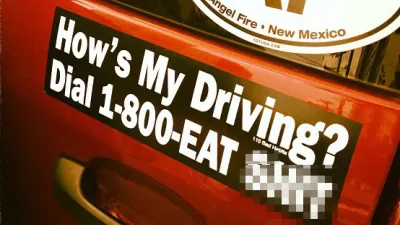

These reforms are sometimes criticized on grounds that, because automobile travel provides freedom of movement, any effort to reduce automobile travel reduces people's freedom. Similarly, critics argue that, by restricting where people live, smart growth is an attack on American's freedom to choose their preferred lifestyle: automobile-dependent sprawl. Even something as innocent as promoting rail transportation improvements can be criticized as a threat:

"Why do politicians love trains? Because they can tell where the tracks go. They know where everybody's going. It's all about control. It is all about power. Politics itself is nothing but an attempt to achieve power and prestige without merit. That is the definition of politics. Politicians hate cars. They have always hated cars, because cars make people free. Not only free in the sense that they can go anywhere they want, which bugs politicians in the first place, but they can move out of the political district that the politician represents."

-P. J. O'Rourke, "Driven Crazy," Reason, November 2009.

These attitudes are somewhat understandable - driving often does seem to provide unrestricted mobility - but it is ultimately an immature vision, like a child rebelling against household rules. True freedom is not simply selfish indulgence, it also also responsibility to avoid harming other people.

Automobile travel contains contradictions: it increases freedom in some ways, it reduces it in others:

- Driving is expensive, so motorists must work more hours or have less money to spend on other goods, a loss of time or fiscal freedom.

- Automobile-oriented land use development disperses destinations, so the faster speeds and direct travel off automobile travel is offset by increased distances, resulting in little or no overall time savings.

- Non-drivers lose freedom, due to reduced travel options (degraded walking and cycling conditions, reduced public transportation and taxi services) and more dispersed land use patterns.

- Crash risk. Fear of crashes reduces people's (particularly children, people with disabilities and low incomes) walking and cycling mobility, and accident injuries and deaths cause severe losses of freedom, as well as economic costs.

- Automobile travel depends on public resources and subsidies, and imposes non-market externalities. It deprives people of freedoms. For example, consumers are often forced to pay for roads and parking facilities regardless of how much they use them: they lack the freedom to say "no" to such costs or to choose alternatives investments and travel options that they may prefer. Similarly, the freedom to drive a noisy motorcycle conflicts with residents' freedom to enjoy quiet.

The question is whether the gains of freedom from automobile travel always offset these losses. Such tradeoffs can be difficult to evaluate. Special interests tend to focus on one perspective while ignoring others.

A test of these issues is to consider the degree that automobile travel is compulsory rather than fully voluntary. Certainly, in automobile dependent communities people generally choose to drive rather than walk, bicycle or use public transportation for most trips, but is that their true preference, or does it reflect a lack of viable alternatives? Described differently, do most consumers really want to drive as many miles as they currently do, or could better alternatives provide greater freedom overall?

For example, is it possible that some motorists would actually prefer a transport system in which walking, cycling and public transportation were more convenient, attractive and affordable, so they could rely more on these alternatives for commuting, and to reduce their need to chauffeur children to schools and recreational activities, or senior parents to medical appointments and shopping?

In many situations, alternative modes provide more freedom than driving, because they are affordable and impose minimal costs to other people. A transportation system maximizes freedom by offering a diverse range of mobility and location options, so people can choose the combination that best meets their needs.

Automobile-oriented transportation systems and land use patterns tend to reduce freedom in many, sometimes indirect and subtle ways. Wider roads and increased motor vehicle traffic volumes and speeds tend to degrade walking and cycling conditions, which also reduces access by walking, cycling and public transit. Dispersed land use patterns, with individual buildings with large parking lots located on busy arterials and highway intersections are difficult to access without a car. Investments in roads and parking facilities reduce the funding available for alternative modes, resulting in a cycle of reduced service, declining ridership and reduced service. This causes major losses of freedom for anybody who, due to physical, legal or financial constraints, lacks unlimited ability to drive.

Economic theory can help guide this analysis. It indicates that, in general, an efficient and equitable transportation system must reflect the following principles:

· Consumer options (also called consumer sovereignty), which means that consumers have viable transportation and location options to choose from.

· Cost-based pricing, which means that the prices of goods and services (including the costs of using roads, parking facilities and fuel) reflect the full marginal cost of providing them unless a subsidy is specifically justified.

· Neutral public policies, which means that planning, funding and tax policies do not arbitrarily favor one transport mode, location or group over others.

Current transportation systems often fail to reflect these principles in various ways. For example, consumers have many options to choose from when purchasing a vehicle, but often have few alternatives to driving, due in part to public policies that underinvest in alternative modes (walking, cycling and public transportation), and land use policies that favor sprawl. The result is a significant loss of freedom overall.

This is not to suggest that driving is always "bad," but it does indicate that automobile travel involves a diverse range of tradeoffs. Although from an individual's short-term perspective (for example, when choosing which mode is most convenient and flexible for a particular trip) automobiles often provides freedom and convenience, it is wrong to conclude that automobile-dependent transportation systems increase freedom and efficiency overall, taking into account all users and impacts. A balanced transportation system, that offers consumers a diverse range of transportation and location options, generally provides the greatest degree of freedom, efficiency and equity.

I am reminded of a similar debate about public smoking. Although a non-smoker, I was initially persuaded that restrictions on smoking in public facilities would be an excessive and unfair restriction on individual's freedom. Yet, once these restrictions were established I quickly realized how intrusive smoking is to other people and experienced the many benefits that result: not only are public buildings much more pleasant environments, we are we all cleaner and healthier, and many smokers finally found it possible to quite because they are less frequently confronted by smoking activity. People who want to smoke have every right to do so, but not in public spaces. Few people I know, even those who smoke, argue for a return to unrestricted public smoking.

Planners are often in the middle of conflicts between different types of freedoms. It is critical that we recognize all the tradeoffs involved, so one person's freedoms do not trample on those of others.

For more information

Wendell Cox (2001), Smart Growth: Delusion, Not Vision: Wendell Cox Closing Statement at Railvolution Conference, Demographia (www.demographia.com/db-sfrailvolu.htm).

James Dunn (1998), Driving Forces; The Automobile, Its Enemies and the Politics of Mobility, Brookings Institute (www.brookings.org).

Kenneth Green (1995), Defending Automobility: A Critical Examination of the Environmental and Social Costs of Auto Use, Reason Foundation (www.reason.org).

Todd Litman (2005), Evaluating Rail Transit Criticism, Victoria Transport Policy Institute (www.vtpi.org); at www.vtpi.org/railcrit.pdf.

Todd Litman (2007), Evaluating Criticism of Smart Growth, VTPI (www.vtpi.org); at www.vtpi.org/sgcritics.pdf.

Randal O'Toole (2000), Is Urban Planning "Creeping Socialism"?, The Independent Review, Vo. IV, No. 4 (www.independent.org). P. J. O'Rourke (2009), "Driven Crazy," Reason, November 2009.

VTPI (2008), "Evaluating TDM Criticism," Online TDM Encyclopedia, Victoria Transport Policy Institute (www.vtpi.org/tdm/tdm49.htm).

James Q. Wilson (1997), "Cars and Their Enemies," Commentary, July, pp. 17-23.

Alabama: Trump Terminates Settlements for Black Communities Harmed By Raw Sewage

Trump deemed the landmark civil rights agreement “illegal DEI and environmental justice policy.”

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

The 120 Year Old Tiny Home Villages That Sheltered San Francisco’s Earthquake Refugees

More than a century ago, San Francisco mobilized to house thousands of residents displaced by the 1906 earthquake. Could their strategy offer a model for the present?

In Both Crashes and Crime, Public Transportation is Far Safer than Driving

Contrary to popular assumptions, public transportation has far lower crash and crime rates than automobile travel. For safer communities, improve and encourage transit travel.

Report: Zoning Reforms Should Complement Nashville’s Ambitious Transit Plan

Without reform, restrictive zoning codes will limit the impact of the city’s planned transit expansion and could exclude some of the residents who depend on transit the most.

Judge Orders Release of Frozen IRA, IIJA Funding

The decision is a victory for environmental groups who charged that freezing funds for critical infrastructure and disaster response programs caused “real and irreparable harm” to communities.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Clanton & Associates, Inc.

Jessamine County Fiscal Court

Institute for Housing and Urban Development Studies (IHS)

City of Grandview

Harvard GSD Executive Education

Toledo-Lucas County Plan Commissions

Salt Lake City

NYU Wagner Graduate School of Public Service