A new report out of Oregon suggests that the fiscal costs of successful resort developments significantly outweigh their benefits -- and taxpayers are burdened with the tab. Erik Kancler of Central Oregon LandWatch explains.

All development comes at a cost. Even the smartest infill development requires dedicated infrastructure capacity and public services. Low density urban sprawl is, of course, more expensive to serve than high density infill, and by extension exurban residential sprawl – especially when located well outside of established urban areas – is even more costly.

All development comes at a cost. Even the smartest infill development requires dedicated infrastructure capacity and public services. Low density urban sprawl is, of course, more expensive to serve than high density infill, and by extension exurban residential sprawl – especially when located well outside of established urban areas – is even more costly.

How much more costly has always been a matter of debate.

And while a new report on the fiscal impacts of destination resorts in Oregon, commissioned by the nonprofit land use group Central Oregon LandWatch and performed by Fodor & Associates, won't end that debate, it lends real credibility to the argument that these large exurban subdivision-oriented developments are not the fiscal boon that their proponents have claimed and that they, in fact, leave local taxpayers with significant costs.

The topic of destination resorts has become perhaps the most contentious land use issue in Oregon since Measure 49, and the issue of costs vs. benefits to taxpayers is a primary focus of the debate. While local county officials, Republican state legislators and the resort industry generally focus on the substantial tax revenues resorts generate, others including many city officials, Democratic state legislators, the state's land use planning agency (the Department of Land Conservation and Development), as well as the vast majority of citizens who have provided public comment on the matter, have begun to seriously question whether the gross tax benefits are outweighed by the costs of serving these developments.

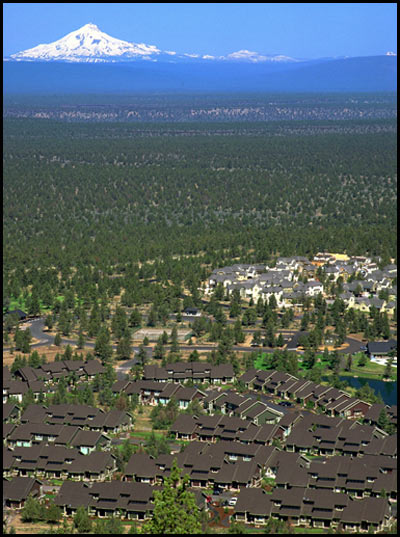

Fodor's analysis focused on one development in particular, the proposed Thornburgh resort near Redmond, Oregon, which in many regards typifies the development model that is now under such heavy fire in the legislature and around the state. The report's primary conclusion regarding the 1,970-acre, 1,375-unit, 3 golf-course proposal is as follows:

The report calculates a $33,408 net cost per residential unit in the proposed development. If that cost were applied evenly to the 22,374 units in Oregon resorts either under construction or proposed, Oregon taxpayers would be saddled with a net costs of $747 million. And that's not counting impacts to nearby cities, which receive no tax benefits or impact fees from these developments, which must bear substantial increases in traffic, and which in many cases lose out on potential property taxes when high-end homes are built in nearby resorts rather than within the cities themselves.

Although industry proponents and local county officials have been quick to blast the report publicly and privately, claiming that it is "flawed" and that its results are "cherry-picked," no one else has yet attempted to quantify the real costs of these developments. Perhaps the reason is that even if the report overestimates the costs by a factor of two and underestimates the tax-benefit by a similar amount, the conclusion would be pretty much the same: destination resorts cost local government and taxpayers money. Whether it's a little money or a lot of money, that's counter to the main justification used by industry proponents for approving resorts, which is that they benefit local governments and taxpayers.

The industry's primary argument in support of the notion that resorts benefit counties financially has been that because these developments aren't fully occupied year-round, the property tax revenues they generate don't have to be spent on infrastructure and services for the resort, and can be used on other county programs. But while counties may indeed end up using the property taxes revenues to boost funding for certain social or other services, the report's conclusions strongly suggest that this is coming directly at the expense of essential public services like roads, fire, police, EMS, and general government facilities.

In theory, if these developments were truly vacant year-round and required no public services, the industry's argument would make sense, and the result would be gobs of free money for the county to spend on whatever it pleased. But there are two fundamental reasons why this argument doesn't hold.

First, whether or not resorts are fully occupied year-round, services and facilities need to be adequate to address their peak occupancy. You can't build a fire-station for only four months of the year, just as you're not likely to find trained professional firefighters to work those stations only four months a year. The same goes for police services, as well as for road networks that must be able to meet peak seasonal capacity, whether or not that capacity is needed year-round.

Second, despite the ultra-low permanent occupancy at historical resorts like Sunriver and Black Butte Ranch which are oriented towards tourism, modern subdivision-oriented resorts actually do appear to have a substantial permanent occupancy. According to a recent analysis of tax records, Deschutes County estimated that approximately 43% of the residential units at one resort – Eagle Crest – are primary residences, far beyond the industry's estimate of 24%.

So whether or not these developments are occupied at levels that are comparable to urban development, the services that they require are, meaning that the "free money" argument doesn't really pan out.

To its credit, the State's Department of Land Conservation and Development seems to understand this. At the Governor's request, DLCD introduced House Bill 2227which earlier this week passed the House by a margin of 31-28 and is now on its way to the Senate. In that bill, DLCD cites that:

And also that:

These concerns, although much further reaching, are right in line with the conclusions of Fodor's analysis, which in many regards paints a far bleaker fiscal picture than even many opponents suspected would be the case. With any luck – and a little prodding – Oregon's State Legislature will pass HB 2227 and initiate a thorough review by DLCD, which seems to possess the political will to tackle this issue.

While Fodor's analysis is specific to Oregon's tax structure, similar developments in other states are likely to yield similar costs. And if Fodor's analysis is accurate, those developments are likely to be subsidized by local taxpayers, too. Indeed, it seems that many of them already are.

Erik Kancler is the Executive Director of Central Oregon LandWatch, a land use advocacy oriented nonprofit based in Bend, OR. Erik has a B.S. in Physical Geography and an M.A. in Geography from U.C. Santa Barbara and has worked previously as a climate scientist, planning consultant, and professional journalist with a focus on land use and the environment. He can be reached at [email protected] or by phone at 541.647.1567.

Alabama: Trump Terminates Settlements for Black Communities Harmed By Raw Sewage

Trump deemed the landmark civil rights agreement “illegal DEI and environmental justice policy.”

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

The 120 Year Old Tiny Home Villages That Sheltered San Francisco’s Earthquake Refugees

More than a century ago, San Francisco mobilized to house thousands of residents displaced by the 1906 earthquake. Could their strategy offer a model for the present?

Opinion: California’s SB 79 Would Improve Housing Affordability and Transit Access

A proposed bill would legalize transit-oriented development statewide.

Record Temperatures Prompt Push for Environmental Justice Bills

Nevada legislators are proposing laws that would mandate heat mitigation measures to protect residents from the impacts of extreme heat.

Downtown Pittsburgh Set to Gain 1,300 New Housing Units

Pittsburgh’s office buildings, many of which date back to the early 20th century, are prime candidates for conversion to housing.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Clanton & Associates, Inc.

Jessamine County Fiscal Court

Institute for Housing and Urban Development Studies (IHS)

City of Grandview

Harvard GSD Executive Education

Toledo-Lucas County Plan Commissions

Salt Lake City

NYU Wagner Graduate School of Public Service