Some planning practices are structurally inequitable. They can result in unfair and wasteful outcomes, such as destruction of vibrant, accessible, minority urban communities for the benefit of more affluent suburban motorists. We can do better!

I just updated my report, "Evaluating Transportation Equity," one of our most important and widely cited publications. It describes practical ways to incorporate distributional impacts into transportation planning. The previous analysis framework included three major categories of equity—horizontal, vertical with respect to ability, and vertical with respect to income—but I’ve long felt those were incomplete. The new framework includes two more categories: external costs and social justice.

|

Previous Framework

Additional Categories

|

Equity analysis is challenging because there are several types, impacts, metrics, and groups of people to consider. Because of this complexity, the best way to incorporate equity into planning is usually to define a set of measurable objectives, such as those in table below. A planning process can then evaluate policies based on whether they support or contradict these objectives.

|

Fair Share |

External Costs |

Inclusivity |

Affordability |

Social Justice |

|

|

|

|

|

This is an important and timely issue. I believe that most planners sincerely want to support equity goals, but the systems we work in sometimes make this difficult. Planning biases can result in very good people making very bad decisions. A good example is the way that urban highways destroyed many vibrant communities and harmed many low-income and minority residents. Let’s consider how this occurred and how we can do better.

Lessons from Urban Highway Planning

During the 20th century, highways displaced many urban neighborhoods. The results were inequitable and inefficient. Those highways were not really essential: many compact and multimodal cities function efficiently with moderate-speed surface streets rather than high-speed highways, and the displaced neighborhoods generally had much better access to jobs and services than the suburbs that those highways were built to serve. These highways harmed low-income and minority communities and reduced accessibility overall. Some cities are now replacing them with surface roads and improvements to other modes.

The planning process that created these highways was classist and racist, as described in Deborah Archer's recent Vanderbilt Law Review article, "White Men’s Roads Through Black Men’s Homes’: Advancing Racial Equity Through Highway Reconstruction."

At the time, planning was often explicitly classist (communities wanted to exclude poor and favor wealthier households) and implicitly racist. Urban planners described low-income and minority community as blight to be displaced when possible. For example, a 1978 Transportation Research Board report, Beneficial Effects Associated with Freeway Construction, gives a sense of planners' thinking at the time. It stated that "Old housing of low quality occupied by poor people often serves as a reason for the destruction of that housing for freeway rights of way."

It also claimed that freeways improve urban aesthetics:

"Blighted or substandard housing, junkyards, dumps, and other sources of ugliness may be eliminated through condemnation, eminent domain, out-right purchase, and other procedures. The effect is a reduction in visual discontinuity to the highway viewer and a possible improvement in the entire visual quality of the affected area and the community."

It further argued that highways provide other environmental and social benefits:

Aesthetics: "The freeway can provide open space, reduce or replace displeasing land uses, enhance visual quality through design standards and controls, reduce headlight glare, and reduce noise.” and “Regarding the visual quality of the highway and highway structures, freeways may create a sculptural form of art in their own right. Some authors note that the undulating ribbons of pavement possessing both internal and external harmony are a basic tool of spatial expression."

Wildlife: "Freeway rights-of-way may be beneficial to wildlife in both rural and urban environments..."

Wetlands: "The intersection of an aquifer by a highway cut may interrupt the natural flow of groundwater and thus may draw down an aquifer, improving the characteristics of the land immediately adjacent to the highway."

Native plants: "Roadside rights-of-way can be among the last places where native plants can grow."

Neighborhood Benefits: "Highways, if they are concentrated along the boundary of the neighborhood, can promote neighborhood stability.” and “Old housing of low quality occupied by poor people often serves as a reason for the destruction of that housing for freeway rights of way."

Social Benefits: "Highways can increase the frequency of contact among individuals...” and “Good highways facilitate church attendance."

Recreation: "Freeways cutting across, through, under, and around the cities afford an excellent opportunity for innovations in recreation planning and design."

I am sorry to see how complicit planners were in promoting and justifying unfair and harmful programs, such as urban highway construction and urban renewal projects. The motivation may have been classism and racism, but the mechanism through which transportation agencies and practitioners achieved these goals was a planning process which valued mobility over accessibility, and therefore prioritized vehicle traffic over walking, bicycling, and public transit. The planning process placed a high value on projected vehicle travel time and cost savings, and ignored the reduction in access and increased costs imposed on urban residents. If considered at all, harms to urban communities were described as intangibles, with the implication that they are difficult to quantify and not very important. Federal and state governments offered large and generous grants for urban highways but virtually no support for affordable and resource-efficient modes.

The article "Paved with Good Intentions: Fiscal Politics, Freeways, and the 20th Century American City," by University of California scholars, concluded that these highways were not cost effective; the project costs, including harms to urban residents, were greater than their mobility benefits.

Consider an example. A six-lane (three lanes each direction) city-to-suburb freeway typically serves 5,000 to 10,000 automobile commuters, assuming 2,000 vehicles per lane-hour during one to three peak hours, a third of which are local trips. Assuming the freeway corridor is five miles long and 600 feet wide, with 30 average residents per acre, it displaced about 10,000 residents. By reducing the supply of affordable homes in high-accessibility neighborhoods the project forced many households to shift from multimodal to automobile-dependent communities. In addition, urban freeways create barriers to local travel, particularly for non-drivers, making trips that could previously be made by a short and pleasant walk or bike ride longer and less pleasant and imposing noise and air pollution on urban neighborhoods.

By measuring mobility benefits but ignoring the reduced accessibility to urban residents, this planning process favored motorists over non-drivers, wealthy over lower-income travelers, and suburban over urban residents. To be more equitable, transportation planning must correct these structural biases.

Most experts now recognize that urban highways were inequitable and often harmful. A new paradigm is changing the way people think about, and planners evaluate, transportation improvements. The new paradigm is accessibility-based, and so recognizes the transportation benefits of compact, multimodal communities. It is also more comprehensive; it recognizes additional goals such as affordability, social equity, more independent mobility for non-drivers, public fitness and health, and environmental quality. As a result, the new paradigm tends to give less support for highway expansions and more support for affordable and resource-efficient modes such as walking, bicycling, public transit and telework.

Categorical Versus Structural Reforms

There are two general types of mitigation strategies, categorical (or programmatic) solutions are policies and programs that target specific groups, and structural changes that affect overall policies and planning activities. Categorical strategies include special policies and programs to benefit specific disadvantaged groups. These include, for example, universal design standards to ensure that transportation facilities accommodate wheelchair users, transit fare discounts for seniors and people with disabilities, and special bus services in high poverty neighborhoods. Structural solutions address inequities more broadly, such as multimodal planning to improve affordable and inclusive travel options; pricing reforms to internalize the congestion, crash risk, and pollution that motor vehicles impose on other people; and Smart Growth development policies that improve affordable housing options in walkable urban neighborhoods.

Categorical solutions often seem most cost effective because they focus resources on a small, clearly-defined group, but structural reforms tend to provide larger and broader benefits, and so are generally most beneficial overall. For example, universal design standards are of little benefit in an automobile-dependent community that has an incomplete sidewalk network, transit fare discounts are of little value in communities with minimal public transit services, and special bus services tend to be inconvenient and inefficient in sprawled communities. Structural solutions, such as multimodal planning, efficient pricing, and Smart Growth policies tend to be more costly and difficult to implement, but provide larger and more diverse benefits, and so can gain broad support.

For example, multimodal planning and efficient pricing can help reduce traffic congestion and infrastructure costs, improve public health, reduce pollution emissions, and support local economic development, in addition to supporting social equity goals. Comprehensive equity planning generally applies both categorical and structural solutions, with emphasis on structural reforms that create more diverse, affordable and efficient transportation systems.

Have We Learned?

People make mistakes; the test of our intelligence is whether we learn from those mistakes and are able to transfer those lessons to new situations. Although contemporary planning attempts to be more inclusive and responsive to the needs of the disadvantaged, many structural biases continue. For example, transportation agencies continue to evaluate transportation system performance based on mobility rather than accessibility, and so favor higher-mileage motorists over people who cannot, should not, or prefer not to drive everywhere. The majority of transportation infrastructure dollars are still dedicated to roads and parking facilities, with only token investments in other inclusive, affordable modes. Few communities are implementing efficient pricing reforms to reduce motor vehicle external costs. Few communities collect the data needed to evaluate equity impacts, such as walking, bicycling, and public transit level-of-service ratings.

Here are my takeaways from previous mistakes so planners can do a better job addressing equity goals in the future.

- Evaluate transportation system performance based on accessibility, not mobility. This recognizes the important roles that walking, bicycling and public transit play in an efficient and equitable transportation system, and recognizes the accessibility provided by compact, connected community development.

- Support affordable infill so any household that wants, particularly those with lower incomes, can find suitable homes in compact and multimodal neighborhoods where it is easy to get around without driving.

- Perform comprehensive transportation demand analysis, particularly the unmet needs of people who are physically, economically, or socially disadvantaged, such as those listed in the box below.

|

- Apply comprehensive impact analysis that considers all costs imposed by transportation facilities and activities, with particular attention to the external costs that highways and motor vehicle traffic impose on non-drivers.

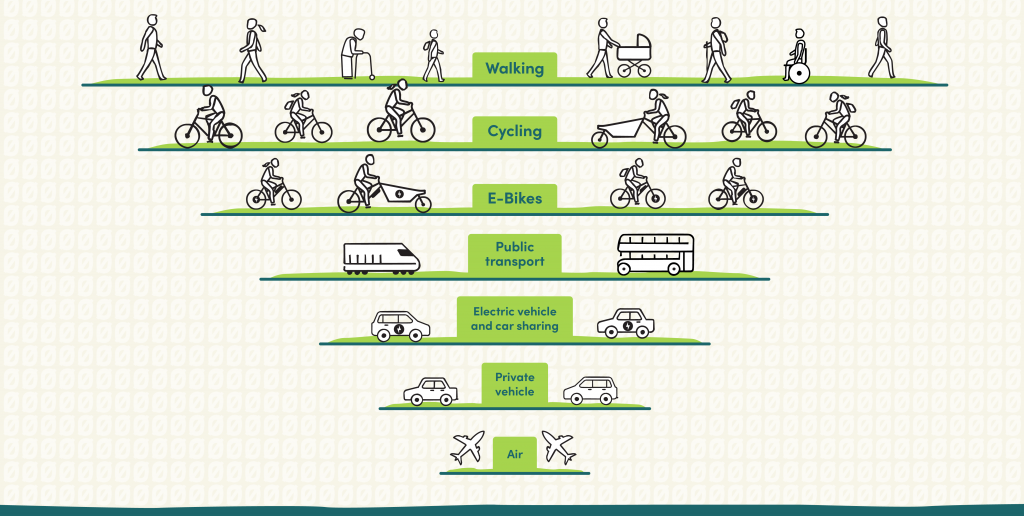

- Favor inclusive, affordable and resource-efficient modes in transportation planning, funding, and facility design. Apply a sustainable transportation hierarchy, which favors walking, bicycling, micromodes, and public transit over low-occupancy automobile travel, as illustrated below.

- Apply least cost transportation planning so that funding currently dedicated to roads and parking facilities can instead be used to improve other modes or support transportation demand management programs if they are more cost-efficient and equitable overall, considering all impacts.

- Implement social justice and affirmative action programs to address injustices from previous planning biases.

- Ensure that disadvantaged groups are effectively involved in the planning process, including access to information on the equity impacts of planning decisions.

What do you think? What structural reforms are needed to ensure that our planning decisions are equitable? What new practices and tools do we need to incorporate equity objectives into decision-making?

For More Information

Kristin N. Agnello (2020), Child in the City: Planning Communities for Children and Their Families, Plassurban.

Deborah N. Archer (2020), “White Men’s Roads Through Black Men’s Homes’: Advancing Racial Equity Through Highway Reconstruction,” 73 Vanderbilt Law Review 1259, Public Law Research Paper No. 20-49.

Samikchhya Bhusal, Evelyn Blumenberg and Madeline Brozen (2021), Access to Opportunities Primer, UCLA Institute of Transportation Studies.

Jeffrey Brinkman and Jeffrey Lin (2019), Freeway Revolts!, Working Paper 19-29, Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia.

Matt Caywood and Alex Roy (2018), Universal Basic Mobility is Coming. And it’s Long Overdue. People Need Easy Access to Work and to Essential Services to Live Decent, Independent Lives, Cities Need Universal Basic Mobility, City Lab.

Hana Creger, Joel Espino and Alvaro S. Sanchez (2018), Mobility Equity Framework: How to Make Transportation Work for People, The Greenlining Institute.

Marisa Jones (2021), Investing in Health, Safety and Mobility, Safe Routes Partnership.

Todd Litman (2021), Evaluating Transportation Equity: Guidance for Incorporating Distributional Impacts in Transport Planning, Victoria Transport Policy Institute.

Todd Litman (2018), Transportation Affordability: Evaluation and Improvement Strategies, Victoria Transport Policy Institute.

Todd Litman and Marc Brenman (2012), A New Social Equity Agenda for Sustainable Transportation, Paper 12-3916, TRB Annual Meeting.

Ryan Martinson (2018), “Equity and Mobility,” Transportation Talk, Vol. 40/2, Summer, pp. 21-44, Canadian Institute of Transportation Engineers.

Chelsey Palmateer and David Levinson (2018), Justice, Exclusion, and Equity: An Analysis of 48 U.S. Metropolitan Areas, Presented at the TRB Annual Meeting.

SDC (2011), Fairness in a Car Dependent Society, Sustainable Development Commission.

Sagar Shah and Brittany Wong (2020), Toolkit to Integrate Health and Equity Into Comprehensive Plans, American Planning Association.

Gregory H. Shill (2020), “Should Law Subsidize Driving?” New York University Law Review 498, Legal Studies Research Paper No. 2019-03.

Hao Wu, et al. (2021), “Urban Access Across the Globe: An International Comparison of Different Transport Modes,” Urban Sustainability.

What ‘The Brutalist’ Teaches Us About Modern Cities

How architecture and urban landscapes reflect the trauma and dysfunction of the post-war experience.

‘Complete Streets’ Webpage Deleted in Federal Purge

Basic resources and information on building bike lanes and sidewalks, formerly housed on the government’s Complete Streets website, are now gone.

The VW Bus is Back — Now as an Electric Minivan

Volkswagen’s ID. Buzz reimagines its iconic Bus as a fully electric minivan, blending retro design with modern technology, a 231-mile range, and practical versatility to offer a stylish yet functional EV for the future.

Healing Through Parks: Altadena’s Path to Recovery After the Eaton Fire

In the wake of the Eaton Fire, Altadena is uniting to restore Loma Alta Park, creating a renewed space for recreation, community gathering, and resilience.

San Diego to Rescind Multi-Unit ADU Rule

The city wants to close a loophole that allowed developers to build apartment buildings on single-family lots as ADUs.

Electric Vehicles for All? Study Finds Disparities in Access and Incentives

A new UCLA study finds that while California has made progress in electric vehicle adoption, disadvantaged communities remain underserved in EV incentives, ownership, and charging access, requiring targeted policy changes to advance equity.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

City of Albany

UCLA Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies

Mpact (formerly Rail~Volution)

Chaddick Institute at DePaul University

City of Piedmont, CA

Great Falls Development Authority, Inc.

HUDs Office of Policy Development and Research