New mobilities—emerging transportation technologies and services—have tantalizing potential. They allow people to scoot, ride, and fly like never before. However, they can also impose surprising problems. How should communities prepare?

Many new transportation technologies and services are currently under development, including e-scooters, microtransit, autonomous taxis, flying cars, and pneumatic tube transport. They have tantalizing potential. They may allow people to scoot, ride, and fly like never before. However, they can also impose surprising problems and costs. How should communities prepare?

This is a timely issue. In the future, communities will face countless decisions concerning how to incorporate emerging mobility technologies and services. Planners can help guide those decisions. To do a good job, we need comprehensive analysis of new mobility impacts.

My new book, New Mobilities: Smart Planning for Emerging Transportation Technologies, transportation, provides the equivalent of product reviews for twelve emerging transportation technologies and services to help communities determine how to minimize their costs and maximize their benefits. The box below lists these new mobilities. Let me share some key insights from my book.

|

New Mobilities

|

A little skepticism is appropriate. Advocates offer images of happy passengers traveling in sleek, fast vehicles, but the reality may be very different. New modes and services are often less comfortable, reliable or affordable than proponents claim. Ridership, revenues and benefits may be much smaller than optimists predict, and they may harm many people overall.

Looking Back to See Forward

To help anticipate our transportation future it is useful to look back at our past. A chapter of my book critically examines how previous transportation innovations affected people and communities. The results are discussed in a previous Planetizen blog, "Our World Accelerated," and a more detailed report.

This research indicates that new transportation technologies are often a mixed blessing: although they can provide large benefits they can also impose large costs, including inequitable harms to non-users.

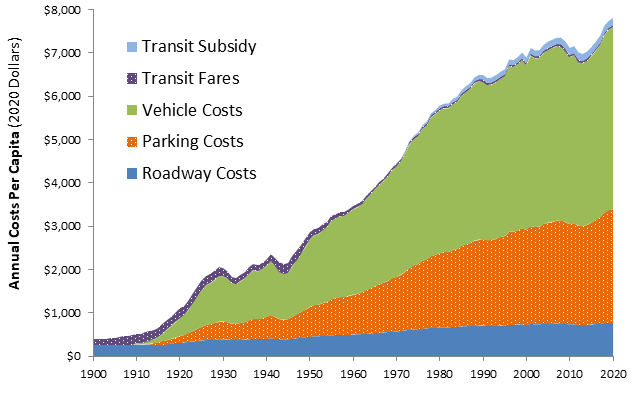

For example, during the 20th century, motorization increased our travel speeds, and therefore the distances that people travel, by an order of magnitude. Before 1900, most people relied primarily on walking, with occasional bike and rail travel, and so averaged about 1,000 annual miles of travel. By 2000, most people relied on automobiles and travelled about 10,000 annual miles. Although this provides benefits, it also imposes significant economic, social and environmental costs, including large increases in household transport expenses, huge increases in road and parking infrastructure costs (see below), new health risks, plus reduced mobility options for people who for any reason cannot, should not, or prefers not to drive for most trips. These costs offset a major portion of benefits, and tend to be inequitable; they harm non-drivers and people with low incomes.

Estimated Per Capita Vehicle and Infrastructure Costs

After a century of automobile-oriented planning, many communities are starting to pushing back; they are limiting vehicle travel, creating more multimodal transportation systems, and favoring compact development over sprawl. Had we applied more comprehensive analysis decades ago, these corrections would not be needed—communities would have maintained balanced transportation systems all along. this has important implications for planning new mobilities.

Comprehensive Evaluation

What factors should we consider when evaluating new mobilities? Industry advocates, who want to attract investors and future customers, emphasize direct user benefits, but there are other impacts and perspectives to consider. Here are a few included in my analysis framework.

Current status

New technologies generally follow a predictable development and deployment pattern, starting with a concept, development, testing and approval, commercial release, product improvement, market diffusion and maturation, saturation, and, finally, decline. This is often called an innovation S-curve, as illustrated below.

Although some advocates claim that new mobilities, such as autonomous taxis, will soon become commercially available and affordable and quickly replace private automobile travel, there are good reasons to be skeptical. Most optimistic predictions are made by people with a financial interest in the industry, based on experience with electronic technologies such as personal computers, digital cameras, and smart phones. However, vehicle innovations tend to be implemented more slowly than other technologies due to high costs, strict safety requirements, and slow fleet turnover. Automobiles typically cost 50 times as much and last ten times as long as personal computers and mobile phones. Consumers seldom purchase new vehicles simply to obtain a new technology. As a result, it usually takes many years for new technologies to become common in the new vehicle market and decades to become common in the fleet.

User experience

It is important to consider how it feels to use a new mobility. Some of the new mobilities that seem most glamourous may actually be unpleasant to use, while others that seem mundane and modest may offer the best user experience. For example, autonomous taxi passengers may sometimes find garbage and odors left by previous occupants, flying cars are likely to be cramped and noisy, and pneumatic tube transport confines passengers into sealed, windowless capsules that accelerate and decelerate with nausea-inducing forces. On the other hand, improving public transit service, active modes (walking and bicycling), and micro-modes (e-bikes and e-scooters) can make local errands and commutes more convenient, comfortable, and enjoyable.

Travel impacts

A key question in the analysis of new modes is how they affect overall travel activity, and therefore traffic problems such as congestion, crash risk, and pollution emissions. Those that reduce total vehicle travel tend to reduce total transportation costs, while those that induce additional vehicle travel tend to increase costs.

For example, because they have lower operating costs and reduce driver stress, electric autonomous vehicles are likely to be driven 10-30% more annual miles, unless implemented with vehicle travel reduction incentives. If parking is priced and roads are not, it will often be cheaper for motorists to program their autonomous cars to circle the block, sometimes for hours, to avoid paying for off-street parking, which will increase urban traffic problems. Similarly, although telework may reduce commute trips, it can encourage workers to choose more sprawled home locations, causing their total vehicle travel and associated costs to increase. To avoid these problems governments will need to implement VMT and sprawl reduction policies.

The table below summarizes my predictions of new mobilities’ travel impacts.

Vehicle Travel Impacts

|

Modes |

Direct Impacts |

Indirect Impacts |

|

Changes how people travel. |

Changes vehicle ownership and land use patterns. |

|

|

Active travel and Micro-mobilities |

Moderate reduction. Reduces many short vehicle trips. |

Large reduction. Supports transit and compact development. |

|

Vehicle Sharing |

Moderate reduction. Reduces automobile travel. |

Moderate reduction. Can reduce car ownership. |

|

Ridehailing and Micro-transit |

Moderate increase due to deadheading. |

Moderate reduction. Can reduce car ownership |

|

Electric Vehicles |

Large increase due to reduced operating costs. |

Small increase. Encourages sprawl. |

|

Autonomous Vehicles |

Large increase due to increased convenience. |

Moderate increase. Encourages sprawl. |

|

Public Transport Innovations |

Moderate reduction. Directly reduces some driving. |

Large reduction. Encourages compact development. |

|

Mobility as a Service (Maas) |

Small reduction. Helps reduces auto travel. |

Small reduction. Helps reduce vehicle ownership. |

|

Telework |

Moderate reduction. Reduces some auto travel. |

Moderate increase. Encourages sprawl. |

|

Tunnel Roads & Pneumatic Tubes |

Small increase. Tunnel roads encourage driving. |

Moderate increase. Encourages sprawl. |

|

Aviation Innovation |

Moderate increase. Encourages air travel. |

Small increase. Air taxis encourage sprawl. |

|

Mobility Prioritization |

Moderate reduction. Shifts auto to shared modes. |

Moderate reduction. Encourages compact development. |

|

Logistics Management |

Moderate reduction. Reduces urban truck travel. |

Moderate reduction. Encourages compact development. |

Travel Speeds and Time Costs

Some new mobilities, such as flying cars and pneumatic tube transport, increase travel speeds, while others, such as public transit service improvements and autonomous vehicles, make travel more convenient and comfortable, which reduces travel time unit costs (dollars per hour of travel). Some only increase speeds for a portion of the trips, so their actual door-to-door time savings are modest. For example, supersonic jets may reduce London-to-New York flight times from seven to four hours, which sounds impressive, but considering the time required to access airports, clear security, check in, and pass through customs and reach destinations, it typically reduces door-to-door travel times from eleven to eight hours, a modest time savings that is only cost effective for people whose time is worth several thousand dollars an hour.

Affordability and Social Equity

New mobility affordability and social equity impacts vary. Some have low costs and serve disadvantaged users, some have high costs per mile of travel but help support an affordable multimodal lifestyle, and some are inherently expensive, as summarized below.

User costs

|

Low Cost |

Contingent (Depends) |

Higher Cost |

|

Active travel and micromodes Public transit innovations Telework |

Vehicle sharing Ridehailing and microtransit Mobility as a Service Mobility prioritization Logistics management |

Electric vehicles Autonomous vehicles Tunnel roads and pneumatic tubes Aviation innovations |

Public Infrastructure Costs

Many new mobilities require significant public infrastructure investments. Active and micromodes have relatively low infrastructure costs but lack dedicated funds and so could require new funding sources. Some, such as vehicle sharing services and Mobility as a Service (MaaS), might require start-up funding but have the potential of becoming self-supporting in the future. Electric vehicles currently receive large subsidies for purchases and recharging facilities. Autonomous vehicles may require large infrastructure investments to support their navigation systems, and dedicated lanes for their use. Tunnel roads, pneumatic tube transport, and aviation innovations may also require expensive new infrastructure; communities will need to decide whether to make these investments and how much to charge for their use.

Traffic Impacts

External traffic impacts (congestion, crash risk, resource consumption, and pollution costs imposed on other people) tend to increase if new mobilities increase total vehicle travel, and decline if they reduce travel. Some, such as ridehailing, telework, and tunnel roads, might increase traffic problems unless implemented with vehicle travel and sprawl reduction incentives. Electric and autonomous vehicles are likely to increase traffic problems unless implemented with strong transportation demand management (TDM) incentives. Although electric vehicles produce zero tail-pipe emissions, they cause other types of pollution, including emissions from tire wear and vehicle-end electricity production. All of these should be considered when evaluating the impacts of new mobilities.

Traffic Impacts

|

Reduces Traffic |

Contingent |

Increased Traffic |

|

Active travel and micromodes Public transit innovations Mobility as a Service Vehicle sharing Mobility prioritization Logistics management |

Ridehailing and microtransit Telework Tunnel roads and pneumatic tubes Aviation innovations |

Electric vehicles Autonomous vehicles |

Public Health (physical activity and contagion risks)

Because they encourage physical activity and are unenclosed, active modes tend to provide the greatest health benefits and the least infection contagion risk. Since most transit trips include walking and bicycling links, public and microtransit innovations also tend to increase public fitness. Telework minimizes contagion risk. Autonomous taxi services, tunnel roads, pneumatic tube transport, and aviation innovations involve sedentary travel in enclosed vehicles and so are least healthy.

Effects on Strategic Planning Goals

Most jurisdictions have strategic goals to reduce automobile travel, increase active travel, create more compact, multimodal communities, and achieve social equity and economic opportunity goals. Affordable and resource-efficient modes, and those that reduce total vehicle travel, tend to help achieve these goals. These include active travel and micromodes, public transit innovations, MaaS, vehicle sharing, mobility prioritization, and logistics management. Because they tend to increase total vehicle travel and sprawl and displace resource-efficient modes, electric and autonomous vehicles, telework, tunnel roads, pneumatic tube transport, and aviation innovations tend to contradict strategic goals unless implemented with strong TDM and sprawl reduction incentives.

Examples of Planning Questions

Here are some examples of some of the questions raised by new mobilities.

Who Builds the Infrastructure? Who Pays? Who Sets the Rules?

Transportation systems require investments by users, governments and businesses. Every time somebody purchases a car, they expect governments to supply roads and businesses to provide parking facilities for their use. We also expect governments to establish traffic rules and liability requirements that protect users and regulations that protect communities from danger and pollution. New mobilities will require new infrastructure planning.

For example, many of the projected benefits of autonomous vehicles, such as reduced congestion, crash risk, and pollution, depend on them having dedicated lanes that allow platooning, i.e., several vehicles driving close together at relatively high speeds. At what point should governments dedicate scarce highway lanes to these expensive vehicles? How much should user pay? Who should be liable if a platoon has a multi-vehicle crash?

Consider another issue. If urban roads are unpriced, it will often be cheaper for autonomous vehicles to drive in circles to avoid paying for parking, although that will increase traffic congestion, traffic risk, and pollution. Should communities regulate or price city streets to prevent these problems?

Similarly, city officials will need to decide whether to build neighborhood terminals for flying cars, whether to allow fast food drone deliveries, and, if so, what rules and taxes should apply.

Planning for Better Mobility

With smart planning we can minimize the problems and maximize the benefits of new mobilities. We need comprehensive analysis of their impacts. Here are some questions that communities should ask when evaluating emerging transportation technologies and services:

- Is it affordable? Can physically, economically, and socially disadvantaged groups use it?

- How will it affect non-users, particularly disadvantaged groups?

- What infrastructure will it require, who should pay, and what regulations should apply?

- How will it affect public health and safety? What risks does it impose on non-users?

- How will it affect community livability, environmental quality, and resource consumption?

- Will it increase or reduce total vehicle travel? Will it increase or reduce sprawl?

My research indicates that, of the 12 new mobilities I analyzed, active modes (walking and bicycling), micromodes (e-bikes and –scooters), and public transport improvements tend to provide the greatest variety of benefits because they are affordable, healthy, and resource-efficient. Vehicle sharing, ridehailing, MaaS, and telework are somewhat more costly and resource intensive but still provide numerous benefits as part of a diverse, multimodal transportation system. Their benefits increase if they are implemented in conjunction with mobility prioritization policies that encourage travelers to choose the most efficient mode for each trip.

Higher-speed modes, including private electric and autonomous vehicles, tunnel roads, pneumatic tube transport, and aviation innovations provide fewer benefits because they are expensive, resource intensive, and impose significant external costs. This is not to suggest that they must be totally forbidden; flying cars, tunnel roads and delivery drones might be appropriate for some trips. However, because of their limited benefits and large external costs, their use should be regulated and priced for efficiency and fairness.

Planners will need to take the lead. To prepare for the future we must frighten, reassure, and analyze. We need to scare decision-makers about the potential risks of New Mobilities. We also need to reassure them that excellent solutions are available. We must identify the specific policies and programs needed to maximize their benefits and minimize their costs.

New mobilities are no panacea. No magic thinking, please! Communities must be discerning; we must be willing to say "no" when necessary to ensure that emerging transportation technologies and services truly benefit everyone.

Key Conclusions

- Numerous new transportation modes and services are under development. Policy makers and practitioners will face countless decisions concerning how new mobilities will be incorporated into communities—whether they should be mandated, encouraged, regulated, restricted, or forbidden in a particular situation.

- We can learn from past mistakes. Many previous transportation innovations, such as private motor vehicles and commercial air travel, were costly to users and communities, which reduced their net benefits and increased inequities. There are many good reasons for communities to favor affordable, healthy, and resource-efficient new mobilities over those that are costly, unhealthy, and resource-intensive.

- New mobilities have diverse benefits and costs, and so require comprehensive analysis of their impacts, including often-overlooked effects related to affordability, social equity, public health, and environmental quality.

- The most glamorous new mobilities, such as autonomous cars, air taxis, and pneumatic tube transport, are costly and provide limited benefits. Policy makers and planners should be skeptical of exaggerated claims of their benefits.

- Many new mobility benefits are contingent; they depend on public policies. With current policies, electric and autonomous cars, telework, air taxis, and pneumatic tube transport are likely to increase total vehicle travel and sprawl, as well as associated costs. Their overall benefits depend on whether they are implemented with TDM incentives that encourage travelers to choose the most efficient mode for each trip, which will often require limiting higher-speed-higher-cost modes.

For More Information

Below are publications related to new mobility evaluation.

My publications

New Mobilities: Smart Planning for Emerging Transportation Technologies (Planner Press 2021)

Not So Fast: Better Speed Valuation for Transportation Planning

Our World Accelerated: How 120 Years of Transportation Progress Affected Our Lives and Communities

Autonomous Vehicle Implementation Predictions

The New Transportation Planning Paradigm

The Future Isn’t What It Used To Be

Other Researchers' Publications

Hana Creger, Joel Espino and Alvaro S. Sanchez (2019), Autonomous Vehicle Heaven or Hell? Creating a Transportation Revolution that Benefits All, Greenlining.

John Eddy and Ryan Falconer (2017), A Civil Debate: Are Driverless Cars Good for Cities?, Doggerel.

Lewis Fulton, Junia Compostella and Alimurtaza Kothawala (2020), Estimating the Costs of New Mobility Travel Options: Monetary and Non-Monetary Factors, National Center for Sustainable Transportation.

Jennifer Henaghan (2018), Preparing Communities for Autonomous Vehicles, American Planning Association.

Shared Mobility Principles for Livable Cities. Principles to guide decision-makers and stakeholders toward the best outcomes for new mobility options.

David Zipper (2021), When Cities Say No to New Transportation Technology, City Lab.

Trump Administration Could Effectively End Housing Voucher Program

Federal officials are eyeing major cuts to the Section 8 program that helps millions of low-income households pay rent.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Ken Jennings Launches Transit Web Series

The Jeopardy champ wants you to ride public transit.

Crime Continues to Drop on Philly, San Francisco Transit Systems

SEPTA and BART both saw significant declines in violent crime in the first quarter of 2025.

How South LA Green Spaces Power Community Health and Hope

Green spaces like South L.A. Wetlands Park are helping South Los Angeles residents promote healthy lifestyles, build community, and advocate for improvements that reflect local needs in historically underserved neighborhoods.

Sacramento Plans ‘Quick-Build’ Road Safety Projects

The city wants to accelerate small-scale safety improvements that use low-cost equipment to make an impact at dangerous intersections.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Heyer Gruel & Associates PA

Ada County Highway District

Institute for Housing and Urban Development Studies (IHS)

City of Grandview

Harvard GSD Executive Education

Toledo-Lucas County Plan Commissions

Salt Lake City

NYU Wagner Graduate School of Public Service