New Zealand’s new national urban development policy prohibits parking minimums and increases allowable building heights near transit stations. This is a watershed moment for the country’s cities and towns.

This blog post was written in collaboration with Stuart Donovan, principal consultant of Transport Advisory and Economics at Veitch Lister Consulting in Brisbane, Australia.

Many good things happen when households live in compact homes located in multi-modal urban neighborhoods. Compared to conventional urban fringe development, residents of compact, multi-modal communities:

- Spend 10-30% less on transportation, including less time driving and reduced delays.

- Consume less energy and produce 20-50% lower pollution emissions [pdf] per capita.

- Have substantially lower traffic casualty rates, are healthier, and live longer.

- Have greater economic mobility (that is, children born in lower-income households are more likely to be economically successful as adults).

- Require less land for roads and parking, which reduces stormwater management costs and heat island effects, and preserves open space (farmland and habitat).

- Reduce costs of providing roads, parking facilities and public services [pdf].

Given these wider benefits, there is a pressing need to tackle planning regulations that hinder the development of compact, multi-model neighborhoods. While consumer surveys indicate many more households do want to live in such communities, a lack of supply often makes this difficult and expensive. Everybody benefits from policy reforms that help satisfy this latent demand, including motorists who enjoy less traffic and parking congestion, and reduced crash risk, when their neighbors shift to non-auto modes.

Recent urban policy reforms in New Zealand provide a model that, we hope, can be copied around the world. Some may scoff at the suggestion New Zealand could be a leader in urban policy. A recent New York Times article, for example, described New Zealand as a “… rural nation of lonely struggle.” Such descriptions are, however, misguided: New Zealand is—and always has been—a highly urbanized country where 87% of the population live in cities and towns, many of which are growing fast. Rapid population growth has collided with restrictions on housing supply, plus geographical and infrastructure constraints, to cause housing unaffordability problems. The Economist’s Global Cities House-price Index indicates that house prices in Auckland—New Zealand’s largest city—have grown 80 percent more than San Francisco since 2000.

New Zealand’s National Policy Statement on Urban Development (NPS), released last Thursday, responds to these issues. Notably from a Smart Growth perspective, the NPS—in one fell swoop—virtually eliminates off-street parking minimums in urban areas (excepting spaces for people with mobility impairments) and sets minimum height limits of six-stories in areas accessible to existing and planned rapid transit stations. These bold initiatives sit alongside a suite of complementary policies designed to enable more compact and affordable infill development.

These policies do not require six-story buildings or eliminate all off-street parking, rather they allow developers to determine the parking supply and building heights that is appropriate given demand. The emphasis on addressing regulations that act as barriers to compact development has enabled the changes to attract support from a diverse coalition, showing how well-designed Smart Growth policies can attract broad support. The Director of the pro-market New Zealand Initiative, for example, penned this recent opinion piece endorsing the removal of parking minimums.

How did the nationwide removal of parking minimums come to pass? The short answer is that these changes represent the culmination of years of experimentation, research, and advocacy. Key developments include:

- In the 1990s, New Zealand’s two largest cities—Auckland and Wellington—removed minimum parking requirements from their city centres as part of comprehensive efforts to support city center redevelopment.

- In 2008, a team of transport researchers commissioned by the NZ Transport Agency—including the now Associate Minister of Transport Julie Anne Genter -- drew on the seminal work of Professor Don Shoup to produce this research report recommending nationwide removal of parking minimums.

- Circa 2010, Auckland started to experiment more widely with trials of demand-responsive parking pricing in the city center. By carefully documenting the success of these trials, and learning from the SFpark trial, Auckland was able to create an evidence base to support the expansion of priced parking into new parts of the city. Around this time, Auckland also began to actively research the economic effects of parking minimums. This study, for example, found the benefits of removing parking minimums exceeded the costs many times over.

- In 2016, and after a lengthy planning process complete with community consultation, Auckland proposed to remove parking minimums from large areas of the city. During the planning process, a civil society group concerned with issues of climate change and housing affordability ran an active campaign to build public support to “bin the mins”, that is, remove parking minimums more widely from across the city.

- In 2016, Auckland Transport also formalized their approach to on- and off-street parking management in this parking strategy. Check out this video as an example of the effort invested into public communications for the strategy.

- Over time, other cities in New Zealand, such as Christchurch and Rotorua, also sought to remove minimum parking requirements from their city centres and adopt demand-responsive parking management practices.

As well as progressing these developments, various professional organizations engaged widely with recognized parking experts to talk about why and how to rationalize parking policies. When Auckland proposed to remove parking minimums, for example, professional engineering and architectural organizations submitted in support of the proposals.

While the experience of Auckland and other cities highlighted the effectiveness of changes to parking policies and height limits, it also highlighted the relatively long time-frames and high costs associated with progressing changes to planning schemes for individual cities and towns. In this context, a key plank of the New Zealand reforms is the willingness of central government to step in. Rather than leaving such changes up to individual cities and towns, central government took action to ensure poor quality and restrictive planning did not stop New Zealand cities growing up rather than out. Urban Development Minister Phil Twyford, for example, observed such policies had “… driven up the price of land and housing, and been a big driver behind the housing crisis. When overly restrictive planning creates an artificial scarcity of land on the outskirts of our cities, or floor space because of density limits in our city centres, house prices are driven up and people are denied housing options.” In making these comments, Twyford stood on a solid and diverse base of evidence and support, carefully constructed by people working over the course of a decade in a wide-range of organizations. And by making these changes at a national level, New Zealand’s reforms go further and faster than most.

What comes next? Well, while most aspects of the changes, such as height limits, apply immediately, the removal of parking minimums has been deferred by 18-months to allow cities and towns time to scale up their parking management policies. The coming months provide an ideal opportunity for urban planners to engage with and address community concerns and misconceptions about the changes. Evidence shows, for example, that residents of compact housing with reduced parking supply located near transit stations generate far fewer vehicle trips (about half) than they would in conventional, automobile-oriented neighborhoods. There is also a need to gather new evidence: By documenting the effects of these changes on land use and transport outcomes, New Zealand can help lay the foundation for further policy initiatives, both locally and internationally.

For More Information

David Baker and Brad Leibin (2018), “Toward Zero Parking: Challenging Conventional Wisdom for Multifamily,” Urban Land.

Paul Barter (2016), On-Street Parking Management: An International Tool-kit, Sustainable Urban Transportation Technical Document #14, GIZ and SUTP (www.sutp.org).

James Brasuell (2019), How Parking Reform Could Relieve the Housing Crisis, Planetizen.

James Brasuell (2019), Everywhere, Signs of Demise for the Planning Status Quo, Planetizen.

CNT (2016), Stalled Out: How Empty Parking Spaces Diminish Neighborhood Affordability, Center for Neighborhood Technology.

The Economist (2017), “Parkageddon: How Not to Create Traffic Jams, Pollution and Urban Sprawl. Don’t Let People Park For Free,” The Economist.

Ríos Flores, et al. (2014), Practical Guidebook: Parking and Travel Demand Management Policies in Latin America, Inter-American Development Bank, (www.iadb.org).

William J. Gribb (2015), “3-D Residential Land Use and Downtown Parking: An Analysis of Demand Index,” CityScape, Vol. 17, No. 1, pp. 71-84.

David Gutman (2017), “The Not-so-Secret Trick to Cutting Solo Car Commutes: Charge for Parking by the Day,” Seattle Times.

Todd Litman (2017), Parking Management: Comprehensive Implementation Guide, Victoria Transport Policy Institute.

Todd Litman (2018), Parking Planning Paradigm Shift¸ Planetizen.

Parking Reform Network is a non-profit organization with a mission to educate the public about the impact of parking policy on climate change, equity, housing, and traffic.

Reinventing Parking is a website the provides ideas for parking policy reforms.

Shoupistas Facebook Page honors the insights of Donald Shoup.

Trump Administration Could Effectively End Housing Voucher Program

Federal officials are eyeing major cuts to the Section 8 program that helps millions of low-income households pay rent.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Ken Jennings Launches Transit Web Series

The Jeopardy champ wants you to ride public transit.

Rebuilding Smarter: How LA County Is Guiding Fire-Ravaged Communities Toward Resilience

Los Angeles County is leading a coordinated effort to help fire-impacted communities rebuild with resilience by providing recovery resources, promoting fire-wise design, and aligning reconstruction with broader sustainability and climate goals.

When Borders Blur: Regional Collaboration in Action

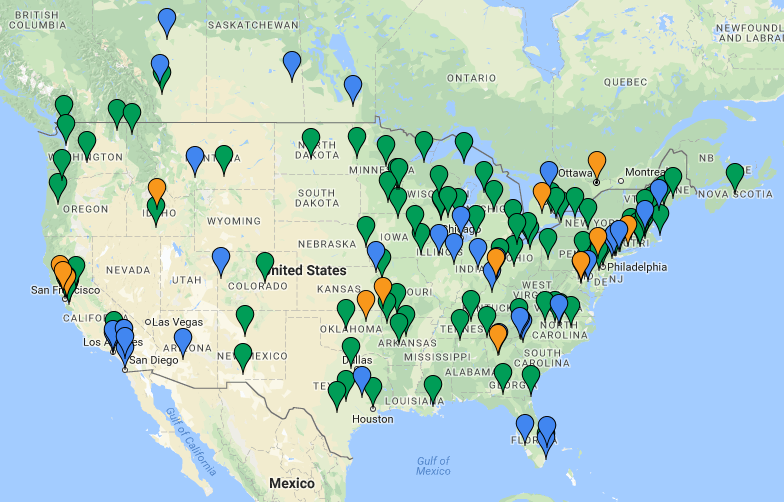

As regional challenges outgrow city boundaries, “When Borders Blur” explores how cross-jurisdictional collaboration can drive smarter, more resilient urban planning, sharing real-world lessons from thriving partnerships across North America.

Philadelphia Is Expanding its Network of Roundabouts

Roundabouts are widely shown to decrease traffic speed, reduce congestion, and improve efficiency.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Ada County Highway District

Clanton & Associates, Inc.

Jessamine County Fiscal Court

Institute for Housing and Urban Development Studies (IHS)

City of Grandview

Harvard GSD Executive Education

Toledo-Lucas County Plan Commissions

Salt Lake City

NYU Wagner Graduate School of Public Service