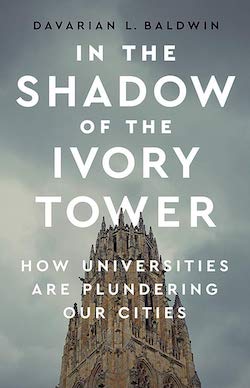

A review of the provocative new book by Davarian L. Baldwin, In the Shadow of the Ivory Tower.

When the fog of Covid-19 lifts and city-dwellers sift through the wreckage to discover which businesses and institutions remain and which have perished, fled, or decamped for the cloud, they likely need not worry about colleges and universities. Notwithstanding the immense challenge they face of sanitizing thousands of students and employees, the vast majority of them probably aren’t going anywhere.

Employers like Hewlett-Packard and Intel are leaving previously invincible places like San Jose. But employers that gave birth to their technologies, like Stanford or Carnegie Mellon, are not likely to leave Palo Alto or Pittsburgh. This is the apotheosis of “eds and meds.”

And yet, in In the Shadow of the Ivory Tower, Davarian Baldwin argues that, for all cities may gain from these institutions, they may already have lost more than they are willing to admit.

Whether city centers play host to flagship campuses, like USC in South L.A., or annexes, like UC Davis’ forthcoming Sacramento outpost, Aggie Square, this economic development strategy meshes nicely with Richard Florida’s ideas about the “creative class,” which consists of well-educated young professionals who want to live urban lifestyles while proximate to other well-educated young professionals.

Whether city centers play host to flagship campuses, like USC in South L.A., or annexes, like UC Davis’ forthcoming Sacramento outpost, Aggie Square, this economic development strategy meshes nicely with Richard Florida’s ideas about the “creative class,” which consists of well-educated young professionals who want to live urban lifestyles while proximate to other well-educated young professionals.

Baldwin does not necessarily argue against the economic benefits of this strategy, insofar as university campuses, along with their research centers, hospitals, and private-sector partners, certainly do create jobs and contribute handsomely to local GDPs. He does, however, contend that colleges’ real estate schemes and general contributions to their respective communities have not always been benign.

Today, colleges present themselves as bastions of progressive thought. But Baldwin implicates them in some serious historic injustices. His biggest villain is the University of Chicago, which occupies what he describes as a fortress-like campus in Chicago’s predominantly Black neighborhood of Hyde Park. He condemns the university for recent controversies like the demolition of a historically Black music club to generational offenses whereby the university went to great lengths to segregate itself from its surroundings. And he is (rightfully) wary of the expansion of the U of C campus police’s jurisdiction beyond the bounds of the actual campus.

Yale University, in New Haven, Connecticut, often gets credit for keeping the city afloat, especially in the ‘70s and ‘80s when many of its factories, including the Winchester rifle company, closed during the country’s wave of postwar deindustrialization. Yet, Yale, like virtually all other nonprofit entities, pays no taxes (local or otherwise). It may pay so-called “payments in lieu of taxes” (“PILOTS”). Meanwhile, it takes tuition from students, reaps tremendous revenues from research, and watches its multibillion-dollar endowment grow while contributing very little to the city’s budget or to its everyday residents.

Baldwin describes the fraught relationship between his own institution, Trinity College, and its host city of Hartford, Connecticut. He calls Trinity a “rural college” for its general lack of engagement with Hartford. A 1970s-era move to close off a public street that bisected the campus and led to a largely Latinx community was part of a larger plan to make the college “a suburban fortress” insulated from its declining “second-tier capital.” That plan gave way to a more community-focused plan called Trinity Heights in the 2000s. Baldwin offers hesitant praise for that plan but notes that ultimately Trinity remains an ivory tower in a struggling city.

New York City might not be struggling, but it too has been pushed around by two behemoth institutions at opposite ends of Manhattan: Columbia University and New York University. In both cases, campus expansion plans have run afoul of surrounding residents. Columbia has been insensitive to disadvantaged communities of Spanish Harlem and Morningside Heights, while NYU has proposed an enormous expansion that, neighbors say, would overwhelm its Greenwich Village location.

For Baldwin, the scheme that most subjugates education to real estate development is that of Arizona State University’s incursion into downtown Phoenix. Baldwin savages the Phoenix area’s historical reliance on real estate as its economic driver and suggests that ASU exploited the city’s growth-friendly culture to get a sweetheart deal for a cluster of buildings downtown. The school pitched the campus as a way to revitalize Phoenix’s notoriously sleepy downtown. Baldwin argues that it disregarded the presence of an existing community of residents and small businesses that stood to be displaced by, or fail to benefit from, the development of enormous academic buildings. He further contends that the university’s private-sector partners will get to occupy untaxed buildings while generating untaxed profits for the university.

All of this should give cities pause when they consider their relationships with universities and, especially, the benefits of their development plans. The self-serving, and sometimes racist, behaviors of universities surely demand reconsideration of their commitments to the common good. But Baldwin does not quite make the case that he seemingly wants to make—that universities and the “eds and meds” economic development strategy are necessarily bad.

Baldwin’s case studies are exacting and detailed. But, in relying on case studies, he neglects to conduct, or at least report on, proper economic analysis. We of course decry displacement and segregation on moral grounds. And, yes, the idea that a university is a “hedge fund with classes” is a nice barb. But that could be said about anything. What is a city but a pension fund that issues parking tickets? If “eds and meds” isn’t a great economic development strategy, what alternatives should cities seek?

Should New Haven have given Winchester tax breaks to stay? Was it a more valuable economic asset than Yale University? Do more low-income Phoenix residents benefit from the cafes and laundries that used to stand where ASU’s Cronkite School and research centers stand now? In the absence of universities, would Hartford, New Haven, and the South Side really be better off? Would their city leaders have come up with foolproof economic development plans? Or would they have continued to fade? How should cities cultivate relationships with universities while upholding the public trust?

Baldwin also neglects to acknowledge that cities give companies incentives all the time. Their efficacy is debatable. But, in this case, a full accounting would have to compare the relative benefits and expenses of university-related incentives versus those offered to for-profit employers. As for community benefits agreements: they are for planners to work out. Baldwin’s title suggests that universities are “plundering” American cities. That’s a strong word, and he provides weak evidence to support it in full. Equally strong words are “swallowed” and “ate,” both of which appear in different chapter names to describe what universities are doing to cities but seem more emotional than empirical.

In the spirit of intellectual discourse, In the Shadow of the Ivory Tower is best seen as a provocation: a necessary call to give cities and universities pause before they plow ahead with any seemingly righteous real estate project. It does not, though, offer an authoritative account of the state of urban universities today. He gives little sense of how widespread these trends are. The half-dozen schools on which he focuses may be poster children for a broader trend—or they could be anomalies.

Ultimately, universities deserve scrutiny form their host cities. But they also deserve appreciation and cooperation. Universities remind us of how satisfying in-person communion and collaboration are. At their best, they are microcosms of and models for cities. They are what cities can aspire to post-pandemic, and hopefully many of them will help cities bounce back.

In the Shadow of the Ivory Tower: How Universities are Plundering Our Cities

Davarian L. Baldwin

Bold Type Books

March 2021

$28.00

Alabama: Trump Terminates Settlements for Black Communities Harmed By Raw Sewage

Trump deemed the landmark civil rights agreement “illegal DEI and environmental justice policy.”

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

The 120 Year Old Tiny Home Villages That Sheltered San Francisco’s Earthquake Refugees

More than a century ago, San Francisco mobilized to house thousands of residents displaced by the 1906 earthquake. Could their strategy offer a model for the present?

Housing Vouchers as a Key Piece of Houston’s Housing Strategy

The Houston Housing Authority supports 19,000 households through the housing voucher program.

Rural Population Grew Again in 2024

Americans continued to move to smaller towns and cities, resulting in a fourth straight year of growth in rural areas.

Safe Streets Grants: What to Know

This year’s round of Safe Streets for All grant criteria come with some changes.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Clanton & Associates, Inc.

Jessamine County Fiscal Court

Institute for Housing and Urban Development Studies (IHS)

City of Grandview

Harvard GSD Executive Education

Toledo-Lucas County Plan Commissions

Salt Lake City

NYU Wagner Graduate School of Public Service