In Louisville, scene of multiple instances of police violence in recent weeks, low-income and Black populations living in neighborhoods dealing with decades of industrial pollution are now suffering the worst public health outcomes of COVID-19.

"Bluntly put, some neighborhoods are likely to kill you," observed Brown University sociologist John Logan in 2003.

In 2020, we can confirm that some neighborhoods have killed people. Far too many communities are facing environmental degradation today. Low-income men in the United States live five fewer years in the five dirtiest mid-size cities (as measured by the U.S. EPA) than in the five cleanest, while low-income women live almost four fewer years. Recent evidence also indicates that COVID-19 is striking particularly hard in the same polluted neighborhoods.

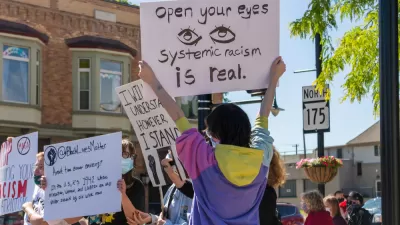

The tragedy is that these public health disparities do not have to persist. But until our nation’s leadership acknowledges and faces up to this reality, or bottom-up community organizing forces the issue, this tragedy will continue.

Environmental racism has long been evident in cities throughout the nation, even before the 1999 publication of Robert Bullard’s seminal book Dumping in Dixie. Louisville, Kentucky is a typical mid-size city that provides a case study of what is going on around the nation. Recent studies of the social determinants of health in Louisville found that life expectancy varies by ten years between the low-income, Black residents in neighborhoods adjacent to a chemical industry park known as Rubbertown compared to the rest of the city.

These studies, endorsed by the mayor of Louisville, Greg Fischer (who is now president of the U.S. Conference of Mayors), and local corporate leaders, blamed the disparities on lifestyle of the poor with the usual suspects: guns, smoking, liquor, diet, and obesity, with a particular emphasis on education. Sociologists call this “blaming the victim.” Missing from this explanation is the plain reality of the direct effects of environmental degradation.

There are parallels with COVID-19 spreading across the United States and the world. The Trump administration’s initial response was to call the novel coronavirus the "Chinese virus," minimize the risks and assume it would fade away with the spring weather. If instead we had aggressively stepped up the production and distribution of tests, the fears and realities would be quite different. Naming a problem is the first step in solving it, be it the current national pandemic or environmental hazards in Louisville and so many other cities

In our case study of Louisville, where Breonna Taylor was killed in March by police, (one of several African Americans killed by law enforcement in recent weeks in Louisville and around the country) followed by protests and violence, we found that those living near environmental hazards have fewer years of healthy life than do other residents of the community, even after accounting for several socio-economic factors. In our research, to be published in the peer reviewed urban affairs journal Local Environment, we found that residents who live within 1.5 miles of EPA designated brownfield sites or within 10,000 feet of Rubbertown have their lives cut short by their exposure to environmental hazards. Even after taking into consideration the effects of neighborhood racial composition, crime rate, income, and age of housing, such proximity remained a statistically significant contributor to the loss of life.

While education is statistically associated with the years of lost life, it clearly is not a causal factor. People with a PhD who contract lung cancer are not less affected than a high school dropout who also has the disease.

It is the case, of course, that better educated people have more resources and can exercise more housing choices, including the means to live far away from environmental hazards. As a practical matter, the solution to environmental justice won’t come from educating hundreds of thousands of people and moving them out of their neighborhoods. Education is part of a long-term strategy, but an immediate question is what to do with current residents.

The failure of Louisville's leadership might also help explain why the city generally ranks at the bottom on poor air quality by EPA estimates of air quality among U.S. cities, as reported in a pre-publication in the medical journal Lancet. This failure is an even more urgent concern today given preliminary evidence that COVID-19, a respiratory disease, has greater adverse effects on people who live near toxic sites and particularly on African Americans, who are more likely to reside in such communities in cities around the country. The link between air pollution and COVID-19 has been reported by the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, while the connections with race have been documented by many scholars and widely reported in the media in recent weeks.

Proximity to environmental hazards and toxic air has not received the proper consideration from political leaders, who must come to terms with the immediate causes of premature death in their community. As the Physicians for Social Responsibility asserted, "We must prevent what we cannot cure."

Remediating older or abandoned industrial sites and reducing emissions from existing sites can create a cleaner, healthier environment. Environmental remediation is not just a local responsibility. Particularly in light of the current national emergency presented by COVID-19, President Trump should immediately re-enact more than 95 Obama-era environmental regulations designed to protect U.S. air, water, and soil rescinded by his administration since 2017. As noted by Nobel Prize winner Al Gore on the Bill Maher show, the irony is that gutting environmental protections will only increase the number of deaths related to COVID-19.

It does appear, however, that U.S. political leadership is coming to terms with COVID-19. Donald Trump called himself a wartime president, at least for a few weeks, during the battle with the virus. We should do the same with other longstanding environmental hazards. Some places do kill, unnecessarily. The first step is to recognize the killer. Then appropriate action can be taken.

Gregory D. Squires is a professor of Sociology and Public Policy and Public Administration at George Washington University.

John Hans Gilderbloom is a fellow for the Neighborhood Associates Corporation, Washington, D.C., and a professor of Urban and Public Affairs at the University of Louisville.

Wesley L. Meares is an associate professor of Political Science and Public Administration at Augusta University.

The authors have no conflicts of interest and there was no funding for this article. The authors also confirm that this submission is original, not under consideration anywhere else that all the authors participated in the preparation of the viewpoint.

Trump Administration Could Effectively End Housing Voucher Program

Federal officials are eyeing major cuts to the Section 8 program that helps millions of low-income households pay rent.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Ken Jennings Launches Transit Web Series

The Jeopardy champ wants you to ride public transit.

Washington Legislature Passes Rent Increase Cap

A bill that caps rent increases at 7 percent plus inflation is headed to the governor’s desk.

From Planning to Action: How LA County Is Rethinking Climate Resilience

Chief Sustainability Officer Rita Kampalath outlines the County’s shift from planning to implementation in its climate resilience efforts, emphasizing cross-departmental coordination, updated recovery strategies, and the need for flexible funding.

New Mexico Aging Department Commits to Helping Seniors Age ‘In Place’ and ‘Autonomously’ in New Draft Plan

As New Mexico’s population of seniors continues to grow, the state’s aging department is proposing expanded initiatives to help seniors maintain their autonomy while also supporting family caregivers.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Heyer Gruel & Associates PA

Ada County Highway District

Institute for Housing and Urban Development Studies (IHS)

City of Grandview

Harvard GSD Executive Education

Toledo-Lucas County Plan Commissions

Salt Lake City

NYU Wagner Graduate School of Public Service