Many people assume that infectious disease risks make cities dangerous, but this is generally untrue. Other factors have more effect on pandemic risk and mortality rates, making cities safer and healthier than rural areas overall.

The following is an excerpt from my new report, "Pandemic-Resilient Community Planning: Practical Ways to Help Communities Prepare for, Respond to, and Recover from Pandemics and Other Economic, Social and Environmental Shocks. This is a timely issue. There is much that we can learn from the COVID-19 pandemic to better prepare for future health, social, and economic threats. Please let me know what you think of this analysis, and if there are more ways that planners can help communities prepare for life's uncertainties.

Comparing Urban and Rural Risks

According to popular culture, the best disaster survival plan is to isolate on a private island, mountain retreat or other rural property. For some people, preparing a secluded bunker with sufficient emergency supplies (“prepping”) is a hobby or business. However, for most households this is an ineffective and unrealistic response. Although an affluent and healthy individual with practical skills and anti-social tendencies may be happy and healthy in rural isolation, most people have responsibilities and dependencies, including work, caregiving, and personal needs, that require access to services, activities and other people, and after a few weeks of hiding alone would die of boredom. There are much better ways to prepare for pandemics and other health, environmental, and economic risks.

In fact, most people are far better off before, during and after a disaster living in an urban area that provides convenient access to essential services and activities than moving to an isolated rural area. Cities are significantly safer and healthier overall, resulting in lower mortality rates and longer lifespans than in rural area, as illustrated below. Rural residents have shorter lifespans due to higher rates of cardiovascular, respiratory and kidney diseases, unintentional injuries lung and colorectal cancer, suicide, diabetes, Alzheimer’s disease and birth defects. These urban-rural differences are even greater for poor and minority groups.

People often assume that infectious disease risks make cities dangerous, but this is generally untrue. Although, all else being equal, contagion exposure tends to increase with density, other factors have more effect on pandemic mortality rates, making cities safer and healthier than rural areas overall.

High Covid-19 infection rates in large cities such as Chicago, New York and Seattle areas reflect their global connections – they are major travel hubs and centers of trade, tourism and migration – more than density. Some dense cities such as Hong Kong, Singapore and San Francisco, and highly urbanized countries, such as Japan, South Korea and Taiwan, minimized Covid-19 deaths through timely control programs, and many urban fringe areas, such as New York suburbs and Kirkland near Seattle, have higher infection rates than nearby central cities, and within New York. Although Covid-19 takes longer to reach rural areas, it eventually reaches them; by early April, two thirds of US rural counties had at least one case, and some have higher than average infection rates.

Coronavirus Case Trajectories Compared

For this analysis it is important to distinguish between density (people per land area, such as per acre) and crowding (people per interior space area, such per 100 square feet). Contagion risks results from crowding, not density. There is no reason to believe that city worksites, stores, and healthcare facilities are more contagious than in rural areas.

Reported COVID-19 Cases (NYT, 25 March 2020)

For this analysis, it is also important to measure risk per capita. Large population states, such as New York, California, and Florida have more virus cases, as indicated above, but many lower density states, such as Louisiana, Georgia, and Nevada have relatively high per capita death rates, as indicated below. Density, it turns out, is less a risk than factors such as long-distance travel (and therefore global connections), public health programs, demographics and lifestyle.

Many lower density states, such as Louisiana, Georgia, and Nevada have relatively high per capita infection rates. (Confirmed cases of COVID-19 per million residents in the USA by state or territory. Source: Wikimedia.)

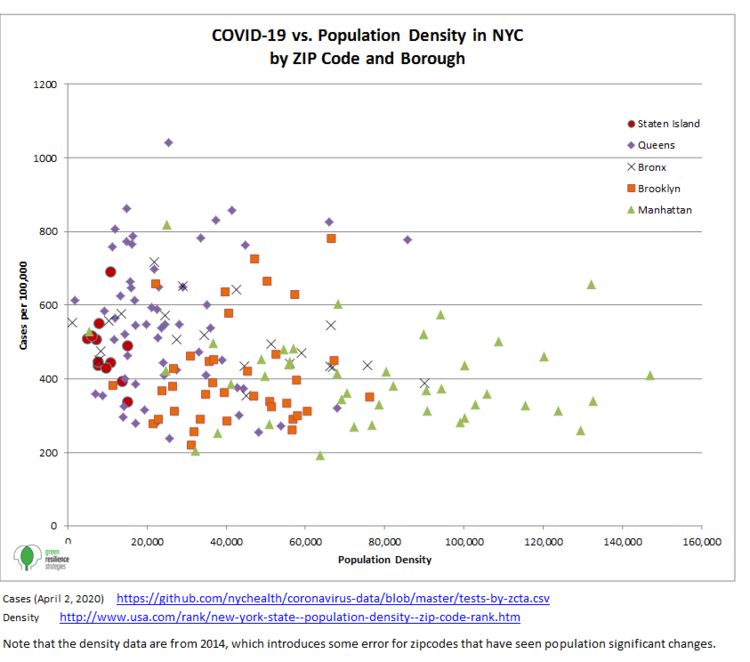

The figure below, from Steve Winkelman's recent column, Mobilizing Against COVID-19 (by Staying Put), shows the negative relationship between neighborhood density and COVID-19 infection rates in New York City. This and other research indicates that low-density, automobile-oriented suburbs tend to have more contagion risk than compact, transit-oriented neighborhoods, probably because the perception that driving is safe encourages motorists to take more trips, travel greater distances, and take fewer precautions than transit users.

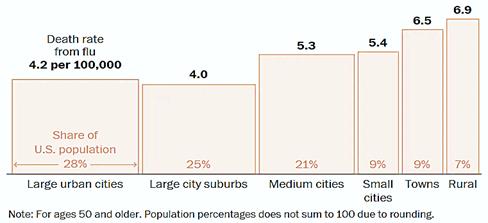

Research indicates that larger and denser cities tend to have longer flu seasons, but less dense areas have greater spikes that can strain health care systems. Rural residents tend to be more vulnerable to infectious diseases due to their demographics (they are older, poorer, and have more chronic diseases and higher smoking rates), limited public health systems, and poor healthcare access. Flu death rates are much higher in rural areas than in large cities and suburbs, as illustrated below. As pandemic expert Professor Eva Kassens-Noor explains, “Rural populations have less means to contract it [coronavirus], but rural populations have less means to treat it.”

Flu Fatality Rates by Location

Flu death rates tend to be higher in rural areas than in large cities or suburbs.

Urbanization tends to increase infectious disease risks but significantly increases physical fitness and health, and significantly reduces most major causes of death (cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, cancers and unintentional injuries), and so increase overall longevity.

Age-Adjusted Death Rates, U.S., 1990–2009

This U.S. study found that mortality rates are lowest in large metro regions and tend to increase with rurality for most demographic groups. Urban-rural mortality disparities are particularly large for poor and most minority groups. These differences have increased during the last two decades.

Health and safety risks vary by location. City residents tend to have greater risks from infectious diseases, high-rise fire and street crime, but exurban and rural residents face greater risks from chronic diseases, accidents and suicides, some disasters (such as wildfires) plus less access to healthcare and slower emergency response, as summarized below.

Health and Safety Risks

Cities |

Exurban & Rural Areas |

|

Infectious disease exposure High-rise fires Street crime |

Chronic diseases Slow emergency response Accidents and suicides Limited public health services Poor access to essential services Some disasters |

All geographic areas have special health and safety risks.

So, what is safer, cities or rural areas? The answer depends, in part, on the scope of analysis, that is, which risks and impacts are considered. Are you only considering pandemic risks, all disaster risks, all health risks, or a broad set of economic, social and environmental impacts? The table below summarizes four ways to frame the question, and the conclusions of this analysis.

Urban-Rural Risk Analysis Scope

Analysis Question |

Conclusions |

| 1. Infectious disease risk. How do infectious disease risks compare? |

Urban areas have greater contagion exposure, but rural residents are more likely to die if infected. |

| 2. Disaster risk. How do total disaster risks compare? |

Urban and rural areas have different risks. Urban areas have faster and better emergency response. |

| 3. Health risk. How do total health risks compare? |

Urban areas have better health outcomes and greater longevity. |

| 4. Total benefits and costs. How do economic, social and environmental impacts vary? |

Urban areas tend to be more resource-efficient and offer better economic opportunities, which tend to provide benefits. |

As a result, any additional contagion risks in urban areas must be balanced against the economic, social, and environmental benefits of more compact living. This is not to suggest that rural living is "bad" and everybody should move to cities; if people prefer a rural lifestyle, they should choose it. This analysis simply indicates that people would be misguided to move from a city to a rural area in the hope that will protect them from pandemic risks; it won't, and it would endanger rural residents.

Rather than abandon cities, resilient community planning would reduce risks, so both cities and rural areas can become safer and healthier overall. There are many practical ways that households and communities can prepare for pandemics and other disaster. To reduce the stresses of quarantines, homes need adequate space, light and ventilation. Houses with ground-floor access have the least contagion exposure. Multi-family housing with shared entrance ways, indoor hallways and elevators have additional risks, but these can be reduced with appropriate design, frequent cleaning and sanitizing, appropriate hygiene, and physical distancing. Homelessness increases contagion risks, so eliminating homelessness increases resilience. Such efforts, while costly and therefore requiring state/provincial and federal funding, provide many long-term benefits.

Travel modes vary in their risks and affordability. All shared vehicles, including airplanes, trains, buses taxi, ridehailing, and private automobiles carrying passengers, can spread contagions. Walking and bicycling tend to have the least contagion risk, can serve people who for any reason cannot drive, provide exercise and are affordable, so improving walking and bicycling conditions tends to increase resilience. Improving walking and bicycling conditions tends to increase health and resilience.

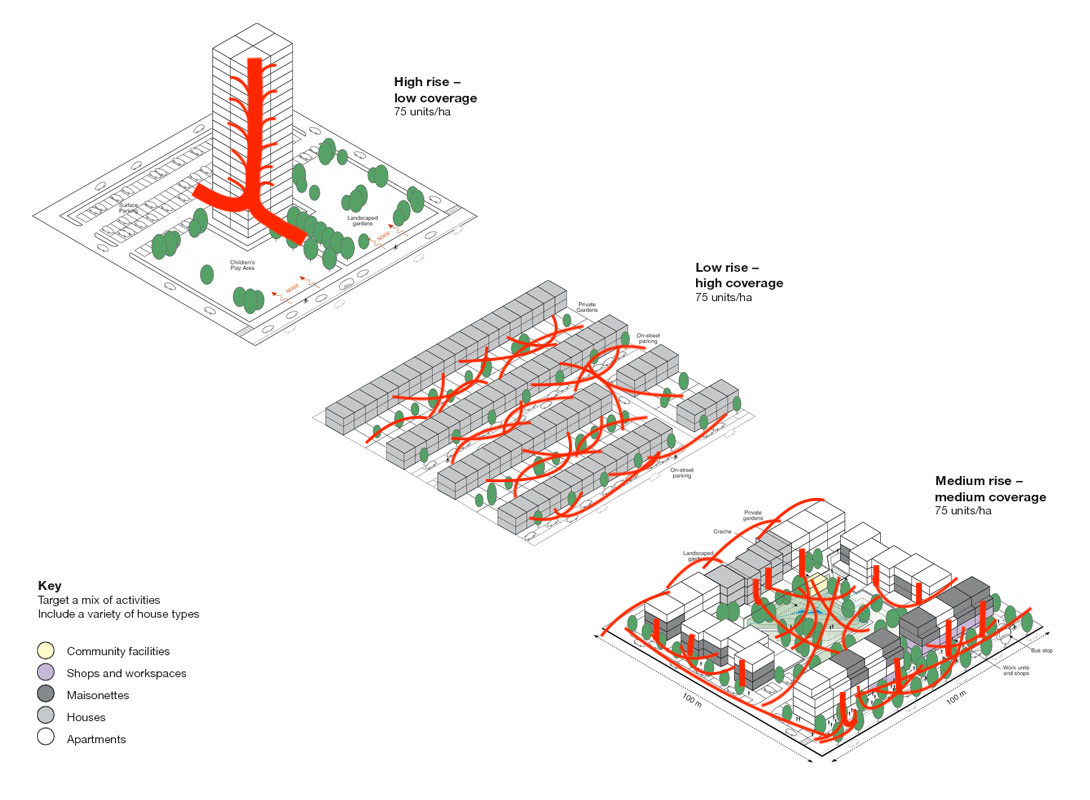

A given density can have very different degrees of contagion risk, depending on building design and pedestrian connectivity. For example, high-rise density tends to have low pedestrian connectivity, particularly if located in an automobile-dependent area were much of the land must be devoted to vehicle parking, while mid-rise density with numerous walkways can provide very high connectivity which minimizes crowding and contagion risks, as illustrated below.

Mid-rise, pedestrian-oriented development tends to maximize community cohesion (the quality of interactions among neighborhoods) and livability. As planner Michael Mehaffy explains in a recent article, "Why We Need ‘Sociable Distancing" shows how moderate-density, walkable development maximizes "eyes on the street," that is, residents ability to maintain social connections among homes, shops and pedestrian, which reduces crime and increases sociability, and therefore urban safety, and therefore health and happiness.

Urban Space as a Web of Connections Where We Can Be, Move, See and Hear

This analysis indicates that, any additional contagion risks in urban areas must be balanced against the much larger potential economic, social, and environmental benefits of compact living. Rather than abandon cities, healthy community planning can reduce the special risks of different types of development, so all communities can become even safer and healthier overall. The table below summarizes special urban and rural pandemic risks, and ways to minimize them.

Special Pandemic Risks and Solutions

Urban |

Rural |

|

| Special Risks |

|

|

| Solutions |

|

|

Pandemics are just one of many risks that communities face, and generally not the most important, so it would be inefficient to implement contagious disease control strategies that increase other problems, for example, by reducing physical activity which increases cardiovascular disease, or increasing vehicle travel and therefore traffic casualties and pollution emissions. Many “win-win” solutions can help reduce pandemic risks and achieve other community goals, such as increasing affordability and economic opportunity, and reducing traffic problems and pollution emissions.

The Covid-19 pandemic is a good learning experience. The bad news: we face diverse and unpredictable risks, with no simple solutions. You could run, but you cannot hide. The good news: cooperative actions can greatly reduce deaths, and most people and communities are highly resilient. Given appropriate support, we can be healthy and happy despite economic, social and environmental shocks.

For More Information

Emily Badger (2020), “Density Is Normally Good for Us. That Will Be True after Coronavirus, Too,”New York Times, 24 March.

Laura Bliss and Kriston Capps (2020), Are Suburbs Safer From Coronavirus? Probably Not, City Labs.

Jake Dobkin and Clarisa Diaz (2020), Coronavirus Statistics: Tracking the Epidemic In New York, The Gothamist (https://gothamist.com).

Reid Ewing and Shima Hamidi (2015), “Compactness Versus Sprawl: A Review of Recent Evidence from the United States,”Journal of Planning Literature, Vol. 30, pp. 413-432 (doi: 10.1177/0885412215595439).

Victoria Hansen, et al. (2016), “Infectious Disease Mortality Trends in the United States, 1980-2014,”Journal of the American Medical Association, Vol. 316, No 20, pp. 2149-2151.

Shima Hamidi, et al. (2018), “Associations between Urban Sprawl and Life Expectancy in the United States”International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, Vol. 15/5 (doi:10.3390/ijerph1505086).

Jack Healy, et al. (2020), “Coronavirus Was Slow to Spread to Rural America. Not Anymore,”New York Times, 8 April.

Dan Keating and Laris Karklis (2020), “Rural areas may be the most vulnerable during the coronavirus outbreak,” Washington Post, 19 March.

Roger Keil, Creighton Connolly and S. Harris Ali (2020), “Outbreaks Like Coronavirus Start in and Spread from the Edges of Cities,”The Conversation.

Don Kostelec (2020), Maintaining Social Distance along Substandard Sidewalks & Pathways, Kostelec Planning (www.kostelecplanning.com).

Todd Litman (2018), Evaluating Public Transportation Health Benefits, American Public Transportation Association (www.apta.com).

Todd Litman (2019), Understanding Smart Growth Savings, Victoria Transport Policy Institute.

Todd Litman (2020), Planning Healthy Communities—Beyond the Hype, Planetizen.

Bill Lindeke (2020), It’s Not Density That’s Driving the American Pandemic, Streets MN.

Michael Mehaffy (2020), Why We Need ‘Sociable Distancing’, The Public Square, Congress for New Urbanism.

Gopal K. Singh and Mohammad Siahpush (2014), Widening Rural-Urban Disparities in Life Expectancy, U.S., 1969-2009,”American Journal of Preventive Medicine, Vo. 46(2), pp. 19-29 (doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.017).

Noah Smith (2020), “New York is a Hot Zone but Not Because of City Living,”Bloomberg News.

Robert Steuteville (2020), “Facts Don't Support the ‘Density Is Dangerous’ Narrative,” Public Square (www.cnu.org).

Transit Center (2020), How Transit Agencies Are Responding to the COVID-19 Public Health Threat.

TUMI (2020), The COVID-19 Outbreak and Implications to Sustainable Urban Mobility – Some Observations, Transformative Urban Mobility Initiative.

UITP (2020), Management of Covid-19 Guidelines for Public Transport Operators, Union Internationale des Transports Publics (International Association of Public Transport).

Jake Dobkin and Clarisa Diaz (2020), Coronavirus Statistics: Tracking the Epidemic In New York, The Gothamist (https://gothamist.com)

Maui's Vacation Rental Debate Turns Ugly

Verbal attacks, misinformation campaigns and fistfights plague a high-stakes debate to convert thousands of vacation rentals into long-term housing.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

San Francisco Suspends Traffic Calming Amidst Record Deaths

Citing “a challenging fiscal landscape,” the city will cease the program on the heels of 42 traffic deaths, including 24 pedestrians.

Defunct Pittsburgh Power Plant to Become Residential Tower

A decommissioned steam heat plant will be redeveloped into almost 100 affordable housing units.

Trump Prompts Restructuring of Transportation Research Board in “Unprecedented Overreach”

The TRB has eliminated more than half of its committees including those focused on climate, equity, and cities.

Amtrak Rolls Out New Orleans to Alabama “Mardi Gras” Train

The new service will operate morning and evening departures between Mobile and New Orleans.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Heyer Gruel & Associates PA

JM Goldson LLC

Custer County Colorado

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

Transportation Research & Education Center (TREC) at Portland State University

Jefferson Parish Government

Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Claremont