Does gentrification always follow massive disinvestment?

In Capital City, a new book that promotes socialist solutions to New York City's housing crisis, Samuel Stein focuses heavily on gentrification, despite the ample evidence that gentrification is in fact fairly rare (which I have discussed here).

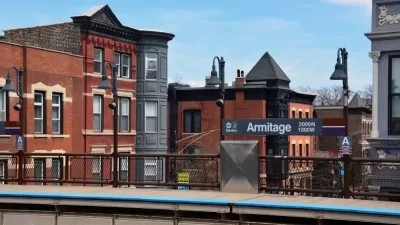

More interesting to me,* however, is his description of how gentrification happens. He writes that cities suffer from a long-term process of "capital flow…first comes investment in a built environment; second, neighborhood disinvestment in property abandonment, and third reinvestment in that same space for greater profits." This statement suggests that gentrification occurs primarily in disinvested neighborhoods. If this was the case, gentrification would occur most frequently in a city’s poorest neighborhoods: for example, the West Side of Chicago.

But in fact, gentrification often occurs in neighborhoods that are not the most disinvested. For example, a recent study of Chicago neighborhoods by Harvard Prof. Robert Sampson shows that black neighborhoods (which, in Chicago, tend to be the poorest) are far less likely to gentrify than white working-class and Latino areas. Similarly, many of Brooklyn's recently gentrified areas, such as North Williamsburg and Greenpoint, were historically white areas. These areas tend to be less poor than the most disinvested areas; in 2000, zip code 11222 (Greenpoint) had a 17 percent poverty rate, roughly comparable to the citywide average. (Williamsburg's zip code has always been poorer because it includes lower-income Hasidic Jews.)

If gentrification is not a response to disinvestment, how does it come about? Here's my alternative theory: most middle-class people tend to prefer short commutes from neighborhoods that they perceive as safe neighborhoods (a category that usually excludes a city's poorest neighborhoods). So if housing were free and abundant, nearly everyone with jobs near central business districts would prefer to live in rich areas near downtown, like New York's Tribeca or Chicago's Gold Coast.

In reality, of course, these desirable areas tend to be more expensive than other areas, because demand for them is high. So if you are priced out of the Gold Coast, where would you live? If your only goal was cheap rent, you would live in a distant suburb or an extremely low-income urban neighborhood. But if you also value safety or a short commute, you might prefer to pay an intermediate amount of rent—which means to live in an area that is only somewhat cheaper than an elite urban neighborhood, but is closer to downtown and safer than the distant suburb or poor neighborhood. Thus, middle-class people priced out of elite neighborhoods might go just a neighborhood or two away from the neighborhood they are priced out of—for example, people priced out of downtown Philadelphia live in Northern Liberties just northeast of downtown, South Philadelphia just south of downtown, or the University City area just west of downtown. Similarly, people priced out of Manhattan's elite neighborhoods go to the outer borough neighborhoods closest to Manhattan rather than going to cheaper outer-borough neighborhoods farthest from Manhattan, and people priced out of Chicago's ritzy lakefront areas go to neighborhoods just west of the lakefront or to the south side of downtown Chicago, rather than to Chicago's truly poor areas. In turn, people priced out of near-downtown neighborhoods sometimes go just a little farther out instead of moving to suburbia. Thus, people priced out of the Brooklyn neighborhoods closest to Manhattan may move to Bushwick or Crown Heights a bit farther out, rather than moving to the outer edges of Brooklyn or to suburbia.

This doesn't mean that gentrifiers never move to poor, disinvested areas; Bushwick is certainly an example of an area that was extremely poor for many decades but is becoming more middle-class. But if they do, it is because such areas are tempting for other reasons, not just because of past disinvestment.

*I note that this point is not at all necessary to Stein's main argument; I just wrote about it because I think it is intellectually interesting. His main argument, to oversimplify radically, is that 1) New York had a housing boom in the last two decades, 2) this boom led to gentrification rather than to lower housing prices, and 3) therefore market-rate housing is bad. In this blog post, I criticize Stein's first assumption.

Alabama: Trump Terminates Settlements for Black Communities Harmed By Raw Sewage

Trump deemed the landmark civil rights agreement “illegal DEI and environmental justice policy.”

Study: Maui’s Plan to Convert Vacation Rentals to Long-Term Housing Could Cause Nearly $1 Billion Economic Loss

The plan would reduce visitor accommodation by 25% resulting in 1,900 jobs lost.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Wind Energy on the Rise Despite Federal Policy Reversal

The Trump administration is revoking federal support for renewable energy, but demand for new projects continues unabated.

Passengers Flock to Caltrain After Electrification

The new electric trains are running faster and more reliably, leading to strong ridership growth on the Bay Area rail system.

Texas Churches Rally Behind ‘Yes in God’s Back Yard’ Legislation

Religious leaders want the state to reduce zoning regulations to streamline leasing church-owned land to housing developers.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Caltrans

Smith Gee Studio

Institute for Housing and Urban Development Studies (IHS)

City of Grandview

Harvard GSD Executive Education

Toledo-Lucas County Plan Commissions

Salt Lake City

NYU Wagner Graduate School of Public Service