The study of gentrification took center stage at the recent conference of the Urban Affairs Association. It's up to planners to put all of that research to good use.

In the day-and-a-half I spent at the annual conference of the Urban Affairs Association (UAA) at UCLA last week, I several times found myself thinking I was at the GAA—Gentrification Affairs Association. Of the conference's 100-plus sessions, I reckon that no fewer than half the discussed topics related to current trends in gentrification, displacement, segregation, and spatial-social equity.

Sessions focused on wealthy but unequal cities like Los Angeles, and on poor and unequal cities like St. Louis. Sessions focused on historical trends like redlining, and current trends like capital-intensive development. Topics were presented from detached scholarly perspectives and from heartfelt, activists' perspectives. Gentrification is happening on the coasts and in the Heartland, north, south, east, and west.

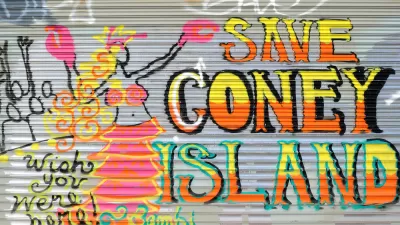

On the one hand, there’s no doubt that gentrification, in its various definitions, poses one of the great urban challenges of our age. It relates to housing prices, housing supply, equity, upward mobility, downward mobility, urban culture, ethnicity, homelessness, and so much more. Studying and responding to gentrification is a humanitarian imperative.

It's also a bit overwhelming when it comes all at once. Here are a few session titles:

- Exploring Gentrification: The US and Beyond

- Culture, Place, and Change: Theorizing Commercial Gentrification

- Mobility and Equity in Urban Environments

- Gentrification in Older Industrial Cities

- Creating a More Equitable City: Narratives of Spatial Production

That's from just one of the session blocks.

I can hardly blame the scholars of UAA for focusing on gentrification. Gentrification offers everything a researcher could want. You can study it theoretically ("the right to the city," etc.), qualitatively (data on rents and relocation), nationally, locally, aesthetically, politically, historically, and contemporaneously. Gentrification, like most urban trends, takes different forms in different places, meaning the topic has as many study-able permutations as there are cities. And, perhaps most importantly, gentrification gives scholars a chance to make real differences if and when their work influences politicians, developers, planners, and stakeholders who set and implement urban policy.

Amid all of these possibilities, the sessions rarely touched on one thing: solutions.

We are living in the golden age of gentrification. It is taking place all over the country, and almost no one has figured out how to stop it, mitigate is effects, or harness its benefits equitably. This burden does not fall on scholars. It falls on planners. Scholars do research, and planners plan. That's the deal. The scholarship reveals that planners need to get going.

Gentrification is reaching true crisis levels, meaning that, absent some bold steps—or even with bold steps—it promises to get worse before it gets better. Eventually, even the scholars are going tire of it. How many papers can you publish, and how many conference sessions can you present at, before you start repeating yourself? And if the scholars get tired of it, imaging how residents feel when they're being priced out of their homes and watching their own neighborhoods turn against them.

Many planners, are, of course deeply concerned about gentrification. Some of them are empowered to make changes; others are not. Still others probably have not wrapped their minds around it yet, or have been prevented from doing so by political considerations. Planners, though, are in a special position. Many of the populations that are threatened by gentrification do not have political clout. If planners don't step up, maybe no one else will. They have to alert their respective elected officials—in case any of them are oblivious or being willfully ignorant. They have to approach aggrieved communities with open minds. They have to convince well-off residents that everyone benefits from equity. And they have to do their darndest to come up with effective policies and outreach programs that encourage all parties to support their policies.

And, contrary to what the naysayers claim, I have to believe that planners can and want to be part of the solution.

Scholars are not necessarily practitioners, but I heard a few pragmatic ideas on these panels. The one I liked the best, because it can be implemented instantly, is that we stop using the term "gentrification." One speaker, on a panel about legacy cities, suggested that “gentrification” is so freighted, fraught, and triggering that its very utterance precludes solutions. It causes people to take sides, get their hackles up, and turn local problems into global crusades.

I tend to agree. As we’ve seen for the past few years, talk is cheap. Planners, scholars, journalists, and activists have uttered “gentrification” millions of times (myself included) in millions of ways, and it hasn't done much good. Planners need to cut through the ill will and promote collaboration.

No solution is going to get it 100 percent right, and no solution can get implemented overnight. It takes far less time to write an academic article than get a plan adopted. But that long timeframe is the reason why everyone concerned with the health of cities needs to embrace a sense of urgency. Someone has to be able to come to a conference with a success story in hand—and soon.

Trump Administration Could Effectively End Housing Voucher Program

Federal officials are eyeing major cuts to the Section 8 program that helps millions of low-income households pay rent.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Ken Jennings Launches Transit Web Series

The Jeopardy champ wants you to ride public transit.

California Invests Additional $5M in Electric School Buses

The state wants to electrify all of its school bus fleets by 2035.

Austin Launches $2M Homelessness Prevention Fund

A new grant program from the city’s Homeless Strategy Office will fund rental assistance and supportive services.

Alabama School Forestry Initiative Brings Trees to Schoolyards

Trees can improve physical and mental health for students and commnity members.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Ada County Highway District

Clanton & Associates, Inc.

Jessamine County Fiscal Court

Institute for Housing and Urban Development Studies (IHS)

City of Grandview

Harvard GSD Executive Education

Toledo-Lucas County Plan Commissions

Salt Lake City

NYU Wagner Graduate School of Public Service