Good research indicates that building middle-priced housing increases affordability through "filtering," as some lower-priced housing occupants move into more expensive units, and over time as the new houses depreciate and become cheaper.

My recent column, "Affordability Trade-offs," advocates a broad definition of affordability that considers middle- as well as low-income households, transportation as well as housing costs, and future as well as current cost burdens (see table below).

Narrow Versus Broad Affordability Analysis

Narrow |

Broad |

|

|

Target populations |

Homeless and low-income households that spend more than 30% of their budgets on housing |

Low- and moderate-income households that spend more than 45% of their budgets on housing and transportation |

|

Time perspective |

Current |

Current and future |

|

Costs considered |

Rents or mortgages |

Rents or mortgages, heating/cooling, maintenance, property taxes and basic transportation |

|

Solutions |

Preserve and build cheap housing through regulations and government subsidies |

Build lots of moderate-priced housing units in walkable urban neighborhoods. |

A narrow definition favors policies that preserve and subsidize cheap housing. A broader definition gives more support to policies that allow much more development of moderate-priced housing ($200,000-600,000 per unit) in walkable urban neighborhoods. Even if the new units are initially too pricey for lower-income households, they increase affordability through filtering, as some lower-priced housing occupants move up to the moderate-priced units, and over time as they depreciate and become cheaper.

There is solid research indicating that filtering occurs, including Stuart Rosenthal's 2014 study, "Are Private Markets and Filtering a Viable Source of Low-Income Housing? Estimates from a 'Repeat Income' Model," published in the American Economic Review, and Miriam Zuk and Karen Chapple’s 2016 study, Housing Production, Filtering and Displacement: Untangling the Relationships [pdf], published by the Berkeley Institute of Government Studies. Similarly, recent research by the City Observatory shows that displacement rates are lower in neighborhoods that increase housing supply and therefore reduce competition for available housing units.

A study by economist Evan Mast described in Daniel Herriges’s, The Connectedness of Our Housing Ecosystem, used an innovative approach to measure filtering impacts. It tracked the previous residences of the occupants of 802 new multifamily developments in 12 North American cities, and the previous residences of the households that replaced them, through six cycles. It found that building market-price apartments causes a kind of housing musical chairs, as households move into new units. This analysis indicates that for every 100 new market-rate units built, approximately 65 units are freed up in existing buildings, accommodating up to 48 moderate- and low-income families.

These studies indicate that increasing housing supply tends to reduce housing prices, particularly over the long-run, although Zuk and Chapple emphasize that subsidies are often needed to deliver enough lower-priced housing to avoid lower-income household displacement.

Some studies suggest that increasing housing supply is ineffective at increasing affordability. Richard Applebaum and John Gilderbloom’s 1983 study, "Housing Supply and Regulation: A Study of the Rental Housing Market," published in the Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, found that cities that had more rental housing construction do not have lower rents or higher vacancy rates. Similarly, Andrejs Skaburskis’ 2006 "Filtering, City Change and the Supply of Low-priced Housing in Canada," published in Urban Studies, using 1996 Canadian census data, found that the filtering process is too slow to significantly reduce low-income households housing burdens.

However, these studies are old and did not account for significant confounding factors. For example, rental housing growth tends to be greatest in attractive and economically successful cities that also have more population growth and higher wages; their rent increases would probably have been higher with less housing supply growth. They also focus on low-income affordability, overlooking middle-income housing costs. Another problem with these studies is that they ignore the additional costs of older houses. Older houses and apartments often have low rents, but these partly reflect their higher operating costs, including greater maintenance and utility expenses, and other undesirable factors such as less safety. Older housing stock can be rehabilitated with weatherization and structural reinforcement, but this is costly; replacement is often more cost effective overall, particularly if the new buildings have more units. As a result, it is unsurprising that areas with more housing supply growth also have less very-low-priced housing, but that does not really mean that in attractive cities, increasing moderate-cost housing supply is ineffective at increasing affordability for moderate- and low-income households.

A paper from Andrés Rodríguez-Pose and Michael Storper claimed that upzoning will worsen, rather than ameliorate inequality and gentrification, based on evidence from a Washington Post article that examined data on changes in home prices by various price tiers, and a study of upzoning effects on land prices in Chicago. As Joe Cortright pointed out in, Will Upzoning Ease Housing Affordability Problems?, the Post's analysis ignored multi-family buildings, and the data actually indicates that supply increases were actually highly correlated with lower rental price inflation. The Chicago study reflected a small number of parcels and a limited time period: it does not really prove that broad upzoning will increase housing prices city-wide.

A study by Dr. John Rose, The Housing Supply Myth analyzed the ratio of household growth to housing unit growth in 33 Canadian metropolitan regions and found that in some areas (notably, Toronto, Vancouver and Victoria), prices skyrocketed although housing units grew faster than households. However, Rose's methodology is criticized by Professor Nathan Lauster and statistician Jens Von Bergmann for failing to account for data problems, particularly changes in data collection methods between census, which counted many previously overlooked housing units, and so exaggerated the growth in housing units. Another major weakness with Rose's study is that it aggregates all housing in a metropolitan region, which in cities like Toronto, Vancouver and Victoria includes many time-shares and student housing. As a result of these problems, Rose's study does not really prove that increasing middle-priced housing supply is ineffective at increasing middle- and lower-priced housing affordability.

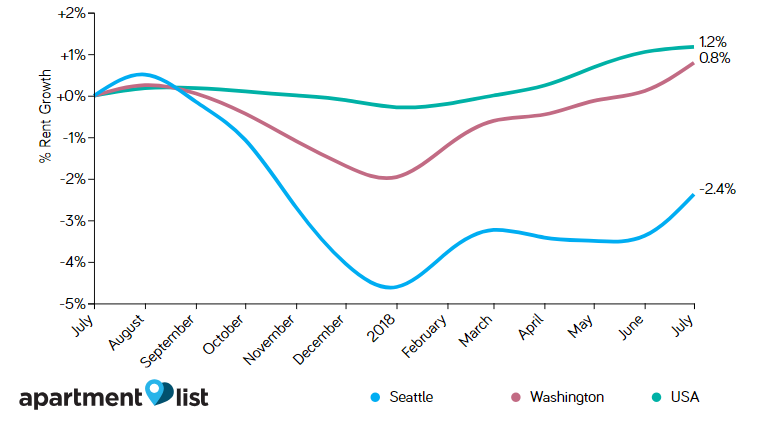

Seattle Rent Growth Over Past 12 Months

Such one-year reductions are insufficient to make these cities truly affordable to lower-income households, and much of these new housing consists of small, city-center high-rises that are unsuited to many households, particularly families with children, but it demonstrates proof-of-concept: building lots of moderate-priced housing increases both low- and middle-income affordability, particularly if maintained for several years. Here in Victoria, where our population grows about 1.5% annually, we call this the 1.5% Neighborhood Affordability Solution. [pdf]

Does |

Does Not |

|

· Increase moderate-income household affordability in the short-run (current year). · Increase low-income affordability in the medium-run (one to three years) as some moderate-income households move from lower-priced units into the new houses. · Increase affordability in the long-run (more than five years) as the new units depreciate in value. |

· Provide quick relief to people with very low incomes or special needs) that require subsidized housing. |

Communities that want true affordability, including middle- as well as low-income households, future as well as current affordability, and transportation as well as housing affordability, should implement policies to allow housing supply in walkable urban neighborhoods to increase faster than population growth.

Let thousands of new houses bloom! Accomplishing this will require zoning code and development policy reforms that make it easy to build lower-priced housing type—multiplexes, townhouses and low-rise apartments—in residential neighborhoods that are currently only allow single-family houses. These policies help reduce housing prices and increase the number of affordable units that can be built with a given housing subsidy. I'll describe these strategies in a future column.

For More Information

Vicki Been, Ingrid Gould Ellen & Katherine O’Regan (2019), Supply Skepticism: Housing Supply and Affordability, Housing Policy Debate, 29:1, 25-40, DOI: 10.1080/10511482.2018.1476899.

Dan Bertolet (2018), Want Less Expensive Housing? Then Make it Less Expensive to Build Housing, Sightline Institute.

Joe Cortright (2017), The End of the Housing Supply Debate (Maybe), City Observatory.

Joe Cortright (2019), Will Upzoning Ease Housing Affordability Problems?, City Observatory.

Filtering YIMBY Wiki.

Emily Hamilton (2018), Is Inclusionary Zoning Creating Less Affordable Housing? Strong Towns. Also see, Emily Hamilton (2019), Inclusionary Zoning and Housing Market Outcomes, Marcatus Center.

Daniel Hertz (2015), What Filtering Can and Cannot Do, City Commentary.

Daniel Herriges (2019), Why are Developers Only Building Luxury Housing?, Strong Towns.

Daniel Herriges (2019), The Connectedness of Our Housing Ecosystem, Strong Towns.

Josh Lehner (2016), Housing Does Filter, Oregon Office of Economic Analysis.

Legalizing Affordable Housing, Sightline Institute.

Evan Mast (2019), The Effect of New Luxury Housing on Regional Housing Affordability, W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research.

Stuart Rosenthal (2014), "Are Private Markets and Filtering a Viable Source of Low-Income Housing? Estimates from a 'Repeat Income' Model," American Economic Review.

Sightline Institute (2019), Cruel Musical Chairs (or Why is Rent So High?) A Simple Reason: We Don’t Have Enough Places to Live (Video).

Old Urbanist (2015), When the Market Built Housing for the Low Income.

Miriam Zuk and Karen Chapple (2016), Housing Production, Filtering and Displacement: Untangling the Relationships, Berkeley Institute of Government Studies.

Maui's Vacation Rental Debate Turns Ugly

Verbal attacks, misinformation campaigns and fistfights plague a high-stakes debate to convert thousands of vacation rentals into long-term housing.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

San Francisco Suspends Traffic Calming Amidst Record Deaths

Citing “a challenging fiscal landscape,” the city will cease the program on the heels of 42 traffic deaths, including 24 pedestrians.

Defunct Pittsburgh Power Plant to Become Residential Tower

A decommissioned steam heat plant will be redeveloped into almost 100 affordable housing units.

Trump Prompts Restructuring of Transportation Research Board in “Unprecedented Overreach”

The TRB has eliminated more than half of its committees including those focused on climate, equity, and cities.

Amtrak Rolls Out New Orleans to Alabama “Mardi Gras” Train

The new service will operate morning and evening departures between Mobile and New Orleans.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Heyer Gruel & Associates PA

JM Goldson LLC

Custer County Colorado

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

Transportation Research & Education Center (TREC) at Portland State University

Jefferson Parish Government

Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Claremont