Common planning practices create automobile-dependent communities where driving is convenient and other forms of travel are inefficient. It's time to recognize the value of transportation diversity.

A federal court recently found that the Wisconsin DOT exaggerated traffic projections to justify a highway widening project. Parking occupancy surveys indicate that in urban neighborhoods, households only need about half as many parking spaces as zoning codes normally require. These are examples of the self-fulfilling nature of automobile dependency.

Automobile dependency refers to communities designed for automobile transport, where it is difficult to access common destinations by other modes. If the planning process assumes that automobile travel demand is growing it will build automobile-oriented transport systems and neglect other travel options. Automobile-oriented planning may have been justified in the 20th century when automobile travel was growing, but vehicle travel is peaking in most developed countries due to demographic and economic trends (e.g., aging population, rising fuel prices, increasing urbanization, changing preferences, etc.), so it makes sense to shift resources previously dedicated to roadway expansions to improving walking, cycling, and public transit.

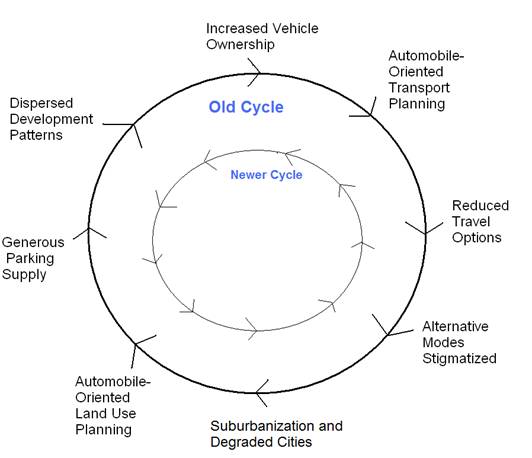

The figure below illustrates this concept: increased vehicle ownership leads to automobile-oriented transport planning, reduced travel options (e.g., degraded walking and cycling conditions, and declining public transit services), stigmatized alternative modes, degraded cities, automobile-oriented land use planning, and developments with generous amounts of required parking, which subsidizes driving and encourages more dispersed development. Of course, each individual step in this cycle seems modest and justified, but their cumulative effects are inefficient and inequitable.

Fortunately, a new cycle is developing which includes more multi-modal planning, more social acceptability of walking, cycling, and public transit, urban redevelopment, smart growth development policies, and more accurate parking requirements. The result is a more efficient and equitable transportation system which allows users to choose the best mode for each trip—walking and cycling for local errands, public transit when traveling on major travel corridors, and automobiles when they are truly most efficient, considering all impacts.

Automobile dependency is harmful in many ways. Of course, it harms non-drivers, that is, people who for any reason cannot, should not, or prefer not to own and operate a motor vehicle, which includes 20-40 percent of travelers in a typical community:

- Youths 10-20 years of age who lack drivers licenses (about 20 percent of total population)

- Seniors over 70 who do not or should not drive (5-10 percent of total population and increasing)

- Adults who cannot drive due to disability or lack of driver’s license (5-10 percent)

- Households with low incomes that want to minimize transportation expenses

- Drivers whose vehicle is temporarily unavailable

- Law-abiding drinkers

- Immigrants, visitors, and tourists who lack a vehicle or driver's license

- People who want to walk or bike for enjoyment and health.

In addition, automobile dependency also harms motorists by increasing their chauffeuring burdens, traffic and parking congestion, and accident risk. Research indicates that even modest reductions in automobile mode share are associated with very large reductions in traffic fatality rates. This indicates that many higher risk drivers, including youths, frail seniors and alcohol drinkers, are willing to reduce their driving provided there are reasonable alternatives. Many of the most cost-effective traffic safety strategies, such as graduated licenses, senior drivers testing, and anti-drunk-driving campaigns become much more successful if implemented with improvements to alternative modes. Examples of such improvements to alternative modes include improved cycling facilities and local bus services to help adolescents get around their communities without a car as well as improved late-night bus and taxi services to entertainment districts to give drinkers alternatives to driving. These improvements reduce risks both to the people who use those alternatives plus risks to responsible motorists who are less likely to become the target of another driver's error.

The challenge for planners is that the conventional solutions to traffic problems tend to exacerbate automobile dependency, while multimodal may seem to increase local traffic problems. For example, expanding roads and parking facilities may seem to reduce local traffic and parking congestion problems, but they degrade walking and cycling conditions and stimulate sprawl, which increases traffic and parking problems overall. In contrast, complete streets, which shift road space to walking, cycling, and public transit, and smart growth policies that encourage infill development, may seem to increase local traffic and parking congestion, although by reducing per capita vehicle ownership and use, actually reduce these problems overall, when measured region-wide or over the long-run. Smart solutions therefore require more comprehensive impact evaluation.

Fortunately, we now have some good success stories. We can now be confident that, by reversing the cycle, we can create more multimodal, and therefore more efficient and equitable, communities.

For More Information

Marlon G. Boarnet (2013), “The Declining Role Of The Automobile And The Re-Emergence Of Place In Urban Transportation: The Past Will Be Prologue,” Regional Science Policy & Practice, Special Issue: The New Urban World – Opportunity Meets Challenge, Vol. 5/2, June, pp. 237–253 (DOI: 10.1111/rsp3.12007).

Jeffrey R. Brown, Eric A. Morris and Brian D. Taylor (2009), “Paved With Good Intentions: Fiscal Politics, Freeways, and the 20th Century American City,” Access 35 (www.uctc.net), Fall 2009, pp. 30-37.

Complete Streets is a campaign to promote roadway designs that effectively accommodate multiple modes and support local planning objectives.

Eric Jaffe (2015), All the Ways Germany Is Less Car-Reliant Than the U.S., in 1 Chart; There Are Rather a Lot of Ways, As it Turns Out, Atlantic CityLab.

Timothy Garceau, et al. (2013), “Evaluating Selected Costs Of Automobile-Oriented Transportation Systems From A Sustainability Perspective,” Research in Transportation Business & Management, Vol. 7, July 2013, pp. 43-53.

ITDP (2012), Transforming Urban Mobility In Mexico: Towards Accessible Cities Less Reliant on Cars, Institute for Transportation and Development Policy.

Santhosh Kodukula (2011), Raising Automobile Dependency: How to Break the Trend?, GIZ Sustainable Urban Transport Project.

Todd Litman (2006), “Transportation Market Distortions,” Berkeley Planning Journal; issue theme Sustainable Transport in the United States: From Rhetoric to Reality?, Volume 19, pp. 19-36; at.

Todd Litman (2013), “The New Transportation Planning Paradigm,” ITE Journal, Vo. 83, No. 6, pp. 20-28.

Todd Litman (2015), Understanding Smart Growth Savings: Evaluating Economic Savings and Benefits of Compact Development, and How They Are Misrepresented By Critics, Victoria Transport Policy Institute.

Peter Newman and Jeffrey Kenworthy (1999), Sustainability and Cities; Overcoming Automobile Dependency, Island Press.

SDC (2011), Fairness in a Car Dependent Society, U.K. Sustainable Development Commission.

Dennis Soron (2009), “Driven To Drive: Cars And The Problem Of 'Compulsory Consumption',” Car Troubles: Critical Studies of Automobility and Auto-Mobility (Jim Conley and Arlene Tigar McLaren eds), Ashgate, pp. 181-196.

Ming Zhang (2006), “Travel Choice with No Alternative: Can Land Use Reduce Automobile Dependence?” Journal of Planning Education and Research, Vol. 25, No. 3, pp. 311-326.

Alabama: Trump Terminates Settlements for Black Communities Harmed By Raw Sewage

Trump deemed the landmark civil rights agreement “illegal DEI and environmental justice policy.”

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

How Atlanta Built 7,000 Housing Units in 3 Years

The city’s comprehensive, neighborhood-focused housing strategy focuses on identifying properties and land that can be repurposed for housing and encouraging development in underserved neighborhoods.

In Both Crashes and Crime, Public Transportation is Far Safer than Driving

Contrary to popular assumptions, public transportation has far lower crash and crime rates than automobile travel. For safer communities, improve and encourage transit travel.

Report: Zoning Reforms Should Complement Nashville’s Ambitious Transit Plan

Without reform, restrictive zoning codes will limit the impact of the city’s planned transit expansion and could exclude some of the residents who depend on transit the most.

Judge Orders Release of Frozen IRA, IIJA Funding

The decision is a victory for environmental groups who charged that freezing funds for critical infrastructure and disaster response programs caused “real and irreparable harm” to communities.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Jessamine County Fiscal Court

Caltrans

Institute for Housing and Urban Development Studies (IHS)

City of Grandview

Harvard GSD Executive Education

Toledo-Lucas County Plan Commissions

Salt Lake City

NYU Wagner Graduate School of Public Service