What can today’s futurists learn from Disney’s unrealized utopia?

Forty years after its opening on October 1, 1982, Disney’s EPCOT theme park remains a mainstay of the massive Walt Disney World properties in Florida. But Disney’s early ambitions for the Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow, then styled E.P.C.O.T., went far beyond today’s theme park complex, encompassing an entire futuristic community featuring the latest technology aimed at making urban life easier, cleaner, and more comfortable.

Inspired by prior planning theories like City Beautiful and the Radiant City, Disney envisioned a master-planned community characterized by maximum efficiency and a strict adherence to design standards. Rather than coming up with solutions to improve conditions in existing cities, Disney, like others before him, dreamt of building the ideal community from scratch, starting with a clean slate to avoid the messiness of older cities and the errors of previous planners. Variously titled “The Florida Project” or “Project X,” E.P.C.O.T. aimed to provide a model of efficiency, productivity, and social harmony.

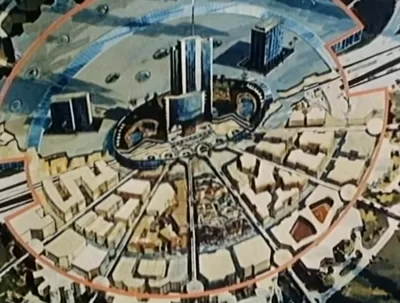

The radial arrangement would center an ‘arrival complex’ complete with a hotel and shopping district enclosed to protect it from the elements and provide a year-round, climate-controlled experience. The central 50-acre shopping area would be enclosed to protect it from the elements, and, while many in the media interpreted this to mean that part of the city would be covered by an enormous dome, Disney scholars argue that the plan was more akin to today’s massive enclosed shopping malls, with some dome-like skylights. Nevertheless, the vision of the ‘domed city’, popularized in the space-obsessed 1960s, has never quite left the popular imagination.

Farther out, high-rise apartment buildings would give way to a green belt, followed by low-density, suburban-style single-family neighborhoods. In other words, it would follow a typical radial model of gradually reduced density, all connected by electrified, automated trams known as WEDway PeopleMovers and a long-distance, high-speed monorail system. The monorails and people movers would shuttle residents around on elevated railways separated from ground-level pedestrian walkways, while cars and trucks would travel underground. The city would feature underground tunnels and pneumatic tubes for trash removal, as well as the latest technology and appliances.

In Disney’s vision, every resident in the town of 20,000 would be employed, primarily at jobs within E.P.C.O.T. or in the town’s industrial office park, a testing ground for the latest technologies—which, of course, E.P.C.O.T. households would be the first to try in their homes and kitchens. The city would never be completed, Disney avowed in a promotional video released just months before his death in 1966, but would “always be introducing and testing and demonstrating new materials and systems.”

To build his dream city, Disney surreptitiously purchased Florida land amounting to twice the size of Manhattan under various shell companies to avoid price gouging and to shield his project from prying eyes. To fully enact his plan, Disney wanted complete, autocratic control of the community, petitioning the Florida state legislature for a number of rights usually reserved for counties, and even receiving the right to generate nuclear power. By lobbying the legislature for the creation of the Reedy Creek Improvement District, in 1967, Disney gained the rights to write building codes, produce electricity, and sell tax-free bonds, among others. There would be no property ownership in E.P.C.O.T., so residents would have none of the rights of traditional homeowners. Like others before him, Disney saw top-down control and planning as the key to making cities better.

Despite this emphasis on central control, Disney appealed to the spirit of “American industry,” striking up collaborations with Westinghouse, IBM, and other tech giants of the day to bring the latest innovations to E.P.C.O.T.. Today’s urbanists will find one of Disney’s ideas about city planning familiar: “I'm not against the automobile, but I just feel that the automobile has moved into communities too much. I feel that you can design so that the automobile is there, but still put people back as pedestrians again, you see.”

With E.P.C.O.T., Disney had a foot in both the worlds of the past and the future. Unfortunately for the project, this left him with no feet to stand on in the present. When Disney died in December 1966, the grand vision for E.P.C.O.T. died with him. As one headline put it, “Epcot Died Ten Minutes After Walt's Body Cooled.” His Imagineers held on to some of his ideals while downsizing the utopian city to a futuristic, multicultural theme park. And while Disney’s Florida theme park empire has indeed sprawled to cover much of the 27,000 acres the company still owns there, there are no extensive car tunnels beneath the Florida swamp, the trash is still taken out largely by above-ground trucks, and there is no nuclear power plant. And while the population of 20,000 never materialized, as of 2015, Disney World did house 44 full-time residents, whose on-site living arrangement comes complete with a vote on ‘municipal’ issues—a privilege Walt did not intend to afford to E.P.C.O.T.’s residents.

Disney’s desire to build whole-cloth communities came partly true with the opening of Celebration, a Disney-developed community in Osceola County, but it remains a far cry from Walt’s hyper-futuristic, automated City of Tomorrow. Meanwhile, other futurists have sought to replicate Walt’s dream of a meticulously planned, efficient, and clean tech utopia, one that will constantly evolve to meet new challenges and adapt to new technologies and transportation modes while somehow keeping poverty and inequality at bay. The ideal of the “smart city” is nothing more than a 21st century attempt to rationalize urban life to maximize efficiency, comfort, and profit through science and technology. While the quest to build the ideal city may spring from well-intentioned technocrats hoping to solve the world’s problems, failures such as Sidewalk Labs’ Quayside project in Toronto—complete with its own leaders Disney-esque in their moonshot dreams and faith in technology and American ingenuity—reveal the inadequacies of technology and automation and the challenges inherent in trying to rationalize the living, unpredictable, often illogical mess of human beings that is a city.

Even though Celebration has failed to live up to its fantastical promises, the company is working on a new crop of ‘Storyliving by Disney’ communities that continue the elusive quest to stubbornly resist reality and instead bring to life brand new, successful, and wholesome communities out of nothing—something even Disney magic may not be able to accomplish.

Alabama: Trump Terminates Settlements for Black Communities Harmed By Raw Sewage

Trump deemed the landmark civil rights agreement “illegal DEI and environmental justice policy.”

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

How Atlanta Built 7,000 Housing Units in 3 Years

The city’s comprehensive, neighborhood-focused housing strategy focuses on identifying properties and land that can be repurposed for housing and encouraging development in underserved neighborhoods.

In Both Crashes and Crime, Public Transportation is Far Safer than Driving

Contrary to popular assumptions, public transportation has far lower crash and crime rates than automobile travel. For safer communities, improve and encourage transit travel.

Report: Zoning Reforms Should Complement Nashville’s Ambitious Transit Plan

Without reform, restrictive zoning codes will limit the impact of the city’s planned transit expansion and could exclude some of the residents who depend on transit the most.

Judge Orders Release of Frozen IRA, IIJA Funding

The decision is a victory for environmental groups who charged that freezing funds for critical infrastructure and disaster response programs caused “real and irreparable harm” to communities.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Caltrans

Smith Gee Studio

Institute for Housing and Urban Development Studies (IHS)

City of Grandview

Harvard GSD Executive Education

Toledo-Lucas County Plan Commissions

Salt Lake City

NYU Wagner Graduate School of Public Service