As the High Line turns ten, a debate about the costs and benefits of urban revitalization continues.

Karrie Jacobs writes about the tenth anniversary of the High Line in New York City, admitting a rediscovered appreciation for the sometimes maligned, but always widely admired, piece of adaptive reused public space.

That renewed appreciation, writes Jacobs, was gained from the perspective offered from the High Line's new neighbor at Hudson Yards, the much less admired Vessel.

Aspects of the elevated walkway that felt overdesigned a decade ago—the benches that sometimes appear to grow directly out of the pavement, the seating areas that step downward toward views of the street, the careful plantings, the blocks of cement with carefully spaced cracks in between—now struck me as generous. Maybe it’s because so much of the world seems contrived today, but there’s a sincerity to it, an honest desire to respond to the needs of the public, to draw them in, to inspire their curiosity, to make them notice the underlying structure of the park, the artworks interspersed with the plantings, and also—maybe especially—to observe the surrounding city.

Jacobs's renewed appreciation of the High Line contrasts with the criticisms of Justin Davidson published earlier this year.

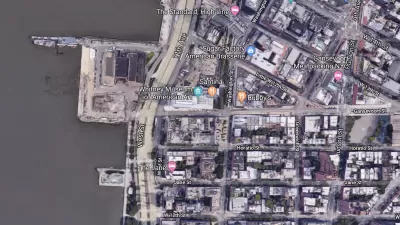

Today, the High Line serves as an elevated cattle chute for tourists, who shuffle from the Whitney to Hudson Yards, squeezed between high glass walls and luxury guard towers. The views are mostly gone, which is a good thing because stopping to admire one would cause a 16-pedestrian pileup. The rail-level traffic mirrors the congestion overhead, caused by construction so hellbent on milking New York’s waning real estate hyper-boom that any patch of land bigger than a tick’s front yard is considered suitable for luxury condos.

Jacobs endeavors to counter other criticisms, too—like the idea that "this park, every new urban park, is an evil act of alchemy." That argument misses an important point, according to Jacobs, about what the neighborhoods around the High Line have become, and what they might have become without the High Line being built.

Would New York be better or worse off without the High Line? The answer depends on whether we (those of us not in the market for a $48 million penthouse, anyway) get any value out of having buildings by Hadid, BIG, Heatherwick, and other luminaries in our city. If the alternative scenario would be the High Line as an undeveloped industrial ruin, surrounded by a West Chelsea of taxi garages and low-rent artists, I’d say screw the starchitects. But the more likely scenario, assuming the High Line hadn’t been restored, would be something that resembles Riverside South, a mostly residential complex some 30 blocks uptown along another disused railroad property. A lineup of 19 buildings with little to recommend them architecturally, they nevertheless remain largely unaffordable to most of us. The High Line, for better or worse, created a context for a kind of residential architecture that hadn’t previously existed in New York City. We couldn’t have gotten the park without the development, but we could easily have gotten the development without the park.

In the end, Jacobs decides that the High Line is an open-air museum of the present moment. The city is radically different than it was ten years ago, Jacobs writes, and the High Line is where to go to immerse in the city of New York as it exists today.

FULL STORY: The High Line at 10

Study: Maui’s Plan to Convert Vacation Rentals to Long-Term Housing Could Cause Nearly $1 Billion Economic Loss

The plan would reduce visitor accommodation by 25,% resulting in 1,900 jobs lost.

North Texas Transit Leaders Tout Benefits of TOD for Growing Region

At a summit focused on transit-oriented development, policymakers discussed how North Texas’ expanded light rail system can serve as a tool for economic growth.

Why Should We Subsidize Public Transportation?

Many public transit agencies face financial stress due to rising costs, declining fare revenue, and declining subsidies. Transit advocates must provide a strong business case for increasing public transit funding.

How Community Science Connects People, Parks, and Biodiversity

Community science engages people of all backgrounds in documenting local biodiversity, strengthening connections to nature, and contributing to global efforts like the City Nature Challenge to build a more inclusive and resilient future.

Alabama: Trump Terminates Settlements for Black Communities Harmed By Raw Sewage

Trump deemed the landmark civil rights agreement “illegal DEI and environmental justice policy.”

Dear Tesla Driver: “It’s not You, It’s Him.”

Amidst a booming bumper sticker industry, one writer offers solace to those asking, “Does this car make me look fascist?”

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

City of Santa Clarita

Ascent Environmental

Institute for Housing and Urban Development Studies (IHS)

City of Grandview

Harvard GSD Executive Education

Toledo-Lucas County Plan Commissions

Salt Lake City

NYU Wagner Graduate School of Public Service