The practice of redlining was outlawed in 1977, but its effects have been indelible.

Last month, incisive new reporting from Aaron Glantz and Emmanuel Martinez at the Center for Investigative Reporting showed, despite rhetoric from President Trump about how good his administration has been for minority communities, that institutional barriers are still preventing black Americans from obtaining wealth through homeownership. In other words, the sad legacy of redlining is still present.

Conservatives today have a hard time explaining these persistent inequalities in ways that do not place the blame on pathologies within the black community. Represented famously by disgraced comedian Bill Cosby’s "Pound Cake speech," and shared by conservative commentators of all stripes, this thinking argues ad nauseum about the usual suspects––single-family households, financial illiteracy, lack of responsibility––and not something more deeply embedded in our institutions. The days of Jim Crow are over, they argue, so quit complaining and take care of yourselves.

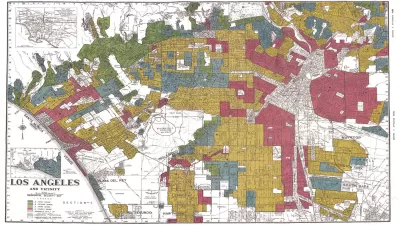

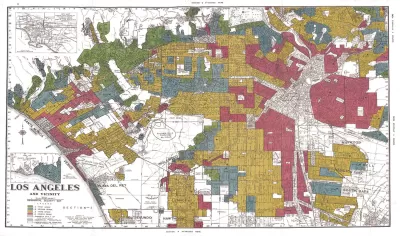

Redlining was a federal policy beginning in the New Deal era that prevented black Americans and immigrants from obtaining loans for homes in certain neighborhoods. The Home Owners' Loan Corporation would take maps of major metropolitan cities and use a color scheme to signal a neighborhood's relative riskiness when it came to home loans. Intuitively, the highest risk neighborhoods were demarcated in red. Those neighborhoods were, not coincidentally, where minorities lived. They would then refuse to underwrite loans to applicants in these neighborhoods, while happily underwriting loans in the "safer" neighborhoods. For decades, the federal government prevented black Americans from being able to purchase and own a home, while subsidizing the homeownership of whites.

According to Glantz and Martinez's reporting, whites in various metropolitan areas are still much more likely than people of color to receive a loan for a house today. In Philadelphia, whites were ten times more likely to receive mortgage loans compared to blacks, Latinos, and Asians in 2015 and 2016. Their analysis showed that "the greater the number of African Americans or Latinos in a neighborhood, the more likely a loan application would be denied there – even after accounting for income and other factors." In the Washington, D.C. metro area, whites were twice as likely to receive loans. Similar numbers are reported for Dayton, Ohio, St. Louis, Atlanta, and many other major metropolitan areas in the United States.

Lenders do not deny these discrepancies, but insist it's due to objective factors such as the credit profile of the customer. Yet Glantz and Martinez offer an example of someone who was repeatedly denied a home loan whom by all reasonable measures should be a good candidate. They profile a black woman in Philadelphia who was employed at the University of Pennsylvania. She tried for several years to get a loan, and was stalled by minor things, such as a $284 unpaid electric bill from an apartment she no longer lived in, which she paid off immediately upon discovering it. Still, she was refused a loan.

She was only offered one after her partner––a half-white woman who worked part time at a grocery store––offered to co-sign. A full time employee at an Ivy League university could only get a loan after co-signing with someone who was making less than $150 every two weeks.

Redlining was outlawed in 1977 under the Community Reinvestment Act, but low income communities still suffer from the legacy of redlining's discrimination. Neighborhoods that were ghettoized and denied lines of credit were sent into downward spirals of poverty. Properties fall into disrepair, which further deters lenders, as credit ratings take these environmental factors into consideration, and not just the risk factors associated with the individual applicant. Lending only returns when whiter, wealthier residents begin to move in and gentrify the area. This phenomenon is rarely simply a private one, driven by the demands of the market. City governments hand out generous tax benefits and subsidies to developers to build low-density, luxury housing.

Housing has long been essential to building intergenerational wealth and stability in America, and it continues to be. In cities across the nation, housing instability is a driver [pdf] of poverty. Housing equity makes up about two-thirds of the wealth for the median household. The overwhelming majority of that wealth has gone to white families, as the government subsidized their mortgages, granting them the benefits of increasing home values, while denying those same benefits to black Americans. As a result, on average black families hold 10 percent of the wealth held by white families.

This wealth gap did not happen by accident, and it doesn't persist because minorities haven't yet figured something out that white Americans did. The game was rigged and the two groups were playing by different sets of rules for more than a century after emancipation, which has huge implications for institutional path-dependence.

Nobel prize winning economist Douglass North first introduced the concept of institutional path-dependence, whereas political and economic institutional arrangements lock themselves in after emerging as a result of unique historical circumstances. Once that happens, as the name suggests, it becomes very hard to change. In the United States, institutional arrangements emerged that relegated blacks to second-class citizens for centuries. Changing laws doesn't automatically change the institutional underpinning, or guarantee good outcomes. Glantz and Martinez's reporting clearly show that despite official legislative protections, the ghost of redlining is still rearing its ugly head.

Jerrod A. Laber is a writer and Free Society Fellow with Young Voices.

Alabama: Trump Terminates Settlements for Black Communities Harmed By Raw Sewage

Trump deemed the landmark civil rights agreement “illegal DEI and environmental justice policy.”

Study: Maui’s Plan to Convert Vacation Rentals to Long-Term Housing Could Cause Nearly $1 Billion Economic Loss

The plan would reduce visitor accommodation by 25% resulting in 1,900 jobs lost.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Wind Energy on the Rise Despite Federal Policy Reversal

The Trump administration is revoking federal support for renewable energy, but demand for new projects continues unabated.

Passengers Flock to Caltrain After Electrification

The new electric trains are running faster and more reliably, leading to strong ridership growth on the Bay Area rail system.

Texas Churches Rally Behind ‘Yes in God’s Back Yard’ Legislation

Religious leaders want the state to reduce zoning regulations to streamline leasing church-owned land to housing developers.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Caltrans

Smith Gee Studio

Institute for Housing and Urban Development Studies (IHS)

City of Grandview

Harvard GSD Executive Education

Toledo-Lucas County Plan Commissions

Salt Lake City

NYU Wagner Graduate School of Public Service