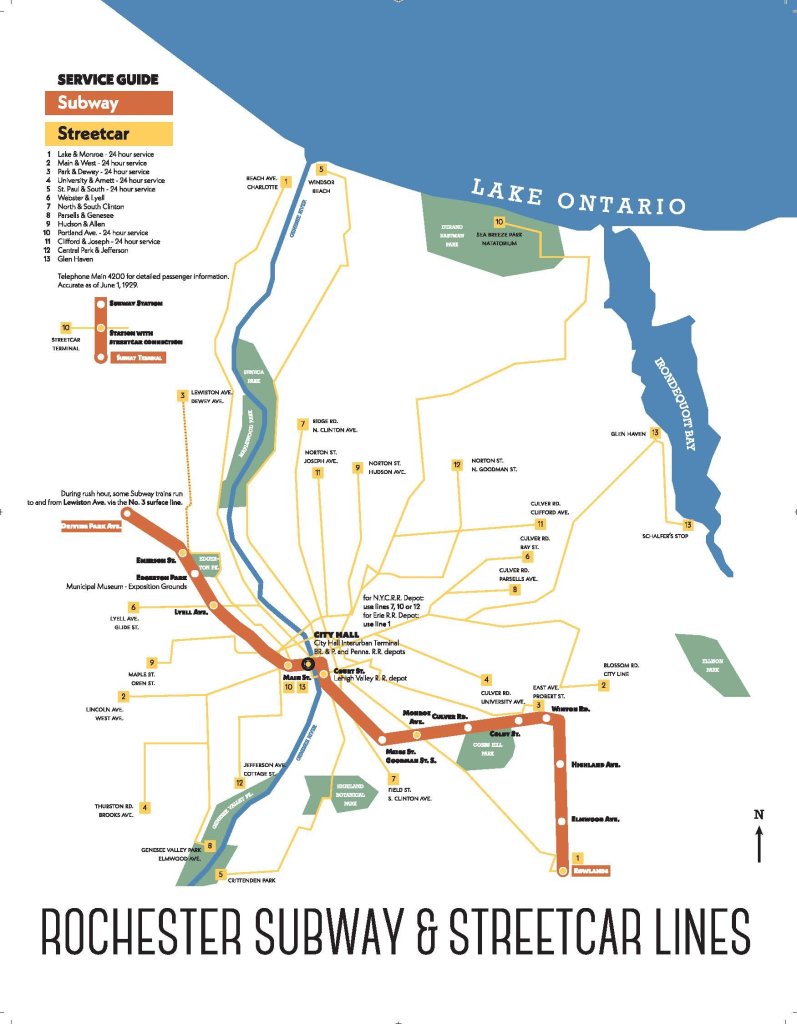

Did you know Rochester, New York, once had a subway? This book excerpt tells the story, complete with a custom map, of the only city in the world to build a subway and then close it.

The following is an excerpt reprinted with permission from Lost Subways of America: A Cartographic Guide to the Past, Present, and What Might Have Been by Jake Berman. Published by the University of Chicago Press. © 2023. All rights reserved.

Rochester, New York — population 211,000 as of 2020 — is the smallest city in North America to ever build a subway system. Rochester also has the unhappy distinction of being the only city in the world to build and operate a full-blown subway system, then abandon it entirely. (Cincinnati partially built its subway but never ran any trains.) By accident of history, the route of the Rochester Subway has evolved to follow the progress of transport technology: first used as a canal in the 19th century, the route was converted to a subway in the 20th century. In the 21st century much of it is used as an expressway.

Rochester grew up around the Erie Canal, the first great public works project of the early American republic. The canal, running from Buffalo on Lake Erie to Albany on the Hudson River, opened in 1825 and provided the first all-water route from the Atlantic to the Great Lakes. Transportation costs dropped by 90 percent, securing New York City’s position as the premier Atlantic commercial port. Rochester grew up where the Erie Canal met the waterfalls of the Genesee River, making the city a logical point to mill Midwestern grain into flour.

By the early 20th century, the canal had served its purpose and was obsolete, due to railroad competition and the opening of the larger New York State Barge Canal in 1918. The old canal bed was primed for redevelopment. Some suggested that the canal be converted to an expressway, but the idea seemed like “impractical or wild dreaming” at the time. Fewer than 3,000 autos existed in the entire county. The final decision was to retrofit the canal for rapid transit. It was thought that the subway conversion would raise property values, strengthen the city’s commercial core, and take interurbans and freight trains off city streets.

The Rochester Subway took six years to build and cost $12 million ($193 million, adjusted for inflation), double the original estimate. At its completion in 1927, the streetcar era was already beginning to wane nationwide. The subway entered a decline after an initial period of optimism. Aside from a short extension to Rochester’s General Motors plant in 1938, the system’s decay continued apace through the Great Depression. Although the subway operated profitably during World War II, it became a money loser after the war. No great measures were taken to save it when the expressway era arrived. Subway ridership peaked at 5.1 million per year in 1947, or about 20,000 average weekday riders — about the same as the ridership in 2019 of the Tren Urbano in San Juan, Puerto Rico.

The expected economic benefits of the subway never really materialized, either. This is chiefly because Rochester never changed its land use patterns to encourage real estate development around the subway stations during the 1920s and 1930s. As discussed in greater detail in the chapter on Dallas, transport and land use decisions are two sides of the same coin. Transit should serve the places where lots of people live and work to be effective. Even at the time, it was considered a major fault that the subway did not serve camera giant Eastman Kodak’s industrial complex, Kodak Park. (For a brief period in the 1920s a few rush-hour subway trains served Kodak Park using preexisting streetcar trackage on the surface, but the routing was short-lived.) Outside of downtown, suburban-style single-family homes surrounded the stations, rather than businesses and apartment buildings. As the Rochester Times-Union editorialized in 1949, “The subway’s fault is that it starts nowhere and goes nowhere.”

By 1952, ridership had dropped so quickly that Sunday and holiday service was eliminated. Passenger service on the Rochester Subway ended June 30, 1956. Freight deliveries on the western half would continue into the 1990s. The eastern half was demolished, and the route was repurposed to carry Interstates 490 and 590, completing the corridor’s evolution from waterway, to railway, to expressway.

Jake Berman is a cartographer, writer, artist, and lawyer. His work has been featured in the New Yorker, Vice, Atlas Obscura, and the Guardian. A native of San Francisco, he now lives in New York City.

Study: Maui’s Plan to Convert Vacation Rentals to Long-Term Housing Could Cause Nearly $1 Billion Economic Loss

The plan would reduce visitor accommodation by 25,% resulting in 1,900 jobs lost.

North Texas Transit Leaders Tout Benefits of TOD for Growing Region

At a summit focused on transit-oriented development, policymakers discussed how North Texas’ expanded light rail system can serve as a tool for economic growth.

Why Should We Subsidize Public Transportation?

Many public transit agencies face financial stress due to rising costs, declining fare revenue, and declining subsidies. Transit advocates must provide a strong business case for increasing public transit funding.

How to Make US Trains Faster

Changes to boarding platforms and a switch to electric trains could improve U.S. passenger rail service without the added cost of high-speed rail.

Columbia’s Revitalized ‘Loop’ Is a Hub for Local Entrepreneurs

A focus on small businesses is helping a commercial corridor in Columbia, Missouri thrive.

Invasive Insect Threatens Minnesota’s Ash Forests

The Emerald Ash Borer is a rapidly spreading invasive pest threatening Minnesota’s ash trees, and homeowners are encouraged to plant diverse replacement species, avoid moving ash firewood, and monitor for signs of infestation.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

City of Santa Clarita

Ascent Environmental

Institute for Housing and Urban Development Studies (IHS)

City of Grandview

Harvard GSD Executive Education

Toledo-Lucas County Plan Commissions

Salt Lake City

NYU Wagner Graduate School of Public Service