An opinion piece by Angie Schmitt reclaims higher ideals for the planning profession.

“What should young people do with their lives today? Many things, obviously. But the most daring thing is to create stable communities in which the terrible disease of loneliness can be cured.” – Kurt Vonnegut

I recently gave a presentation to a group of high school kids, and I struggled a little bit with how to explain to them what an urban planner does. I mean, I knew what the “official” definition would say, something soaring and a little hard to define.

But for some weird reason I wanted to be honest with the students. The reality of it depressed me: Staring at zoning maps? Taking abuse at public meetings?

What is planning for? What does urban planning stand for? I find myself wondering about that in the wake of the pandemic, and pandemic response that had extreme repercussions for public spaces. I find myself disappointed that on the weightier matters, the profession was largely silent.

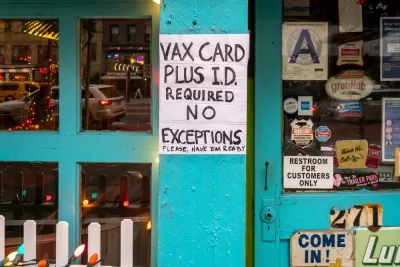

There was an interesting commentary about the pandemic and technology recently in Harpers. The author is based in France, and he talks about how Vaccine Passports have given the government unprecedented private information about the public’s whereabouts and day-to-day activities. French residents needed to present a passport, digitally on a smartphone, to go almost anywhere public, until the rule was lifted in March 2022.

The author is a tiny bit conspiratorial, but one point he made stuck with me. He said big corporations, tech corporations, want us alone in our houses, clicking on screens and feeding their little algorithms so they can mine the data. Our response to the pandemic played right into that—at the expense of in-person interaction, community. I think there’s some truth to that and some of the mental health crisis and other societal fallout we’re seeing right now is an outcome.

In the United States, of course, many of the pandemic restrictions were limited to bluer cities and states. Living in Ohio, I was only asked to present proof of vaccine on two or three occasions.

But that doesn’t mean our policies weren’t restrictive—they just depended a lot on your social status and where you lived. In Cleveland, schools were closed for a year plus. Libraries were closed for a time. At times, especially during the winter, as the mother of young children, I felt like I was almost on house arrest, which will certainly try your mental health when you have young children.

We closed playgrounds even in Cleveland for about a year, going as far as to remove swings all to almost no public outcry and against copious scientific evidence that the risk of outdoor transmission was practically nil.

Other places took policies limiting access to public space and public facilities further, especially for certain groups.

In New York City, where they used vaccine passports for a time because of a low vaccination rate, teenagers were mostly forbidden from all public spaces in New York City from August 2021 to March 2022, when they were lifted. Given disparities in who was vaccinated, it likely had racially unequal impacts on who had access to spaces like restaurants, museums, and theaters.

I understand why the mayor decided to take those measures; obviously we were trying to manage a pandemic that was killing a lot of people. At the same time, I wish we would have had a more robust discussion about the potential for unintended consequences. Excluding certain people from public space based on medical status is pretty unprecedented at such a wide scale, with the exception of enrollment at primary school. And I’ve never been asked to present a medical record to enter a restaurant before.

Moreover, teenagers were at overall low risk and bore a disproportionate burden for our pandemic policies. (If you want to read something disturbing, check out The New Yorker's interviews with NYC teenagers and their experiences during the pandemic; “eventually I found myself not talking to anyone, just being in my room the whole day.” “A lot of the time, I lounge around in my room and kind of just stare at my computer.”) No one even asked, in a serious way, is this treatment fair? Is it just to ask low-risk teenagers to take on such enormous personal sacrifices? What about the consequences to their mental and physical well being?

I wonder sometimes if the profession were more diverse demographically and ideologically, if we weren’t by definition mostly work-from-home professionals, if things would have been different. Even having more moms of young children in the profession would have brought greater visibility to the impacts of playground closures, for example.

It was inevitable that we would make some mistakes in our pandemic response. And no one person is the sole arbiter of the entire response. Different people were affected differently and had dramatically different experiences during the pandemic.

But the inability to discuss tradeoffs in a measured way contributed to some of the harms that disproportionately fell on vulnerable people and eroded the public trust that planners, in my opinion, rely on to do their work. Public trust isn’t an unlimited resource. It has to be earned.

One idea I want to offer for consideration is that certain values ought to be at the core of the profession — the key one being the importance of community. Equal and free access to public and quasi-public spaces to the extent they promote democratic ideals of equality and inclusion. It’s lofty. Maybe a little grandiose and hard to define. But that’s the kind of thing I would have liked to tell those students I do, planners do.

I don’t know if I could say it honestly, though, so I didn’t. And I’m not even sure how much agreement there is about it. But I want to propose that we should think a little more about the core values of our profession and whether we are living up to them in moments of crisis.

Angie Schmitt is a writer and planner based in Cleveland. She is the author of Right of Way: Race, Class and the Silent Epidemic of Pedestrian Deaths in America (Island Press, 2020). She is founding principal at 3MPH Planning, a small Cleveland based firm focused on pedestrian safety.

Alabama: Trump Terminates Settlements for Black Communities Harmed By Raw Sewage

Trump deemed the landmark civil rights agreement “illegal DEI and environmental justice policy.”

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Why Should We Subsidize Public Transportation?

Many public transit agencies face financial stress due to rising costs, declining fare revenue, and declining subsidies. Transit advocates must provide a strong business case for increasing public transit funding.

Understanding Road Diets

An explainer from Momentum highlights the advantages of reducing vehicle lanes in favor of more bike, transit, and pedestrian infrastructure.

New California Law Regulates Warehouse Pollution

A new law tightens building and emissions regulations for large distribution warehouses to mitigate air pollution and traffic in surrounding communities.

Phoenix Announces Opening Date for Light Rail Extension

The South Central extension will connect South Phoenix to downtown and other major hubs starting on June 7.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Caltrans

Smith Gee Studio

Institute for Housing and Urban Development Studies (IHS)

City of Grandview

Harvard GSD Executive Education

Toledo-Lucas County Plan Commissions

Salt Lake City

NYU Wagner Graduate School of Public Service