Transit-rich, “inner ring” neighborhoods with multi-family, mid- and high-rise housing (going beyond the limits of missing middle housing) will be necessary to deliver access to high-quality, safe, and affordable housing.

The Problem

Like the climate and public health crises, the current housing affordability crisis is a result of decades-long neglect, supercharged by the global Covid-19 pandemic. In New York, the situation is dire and a perennial source of angst. Prior to the pandemic, the housing affordability crisis was at a fever pitch. According to the 2017 New York City Housing and Vacancy Survey, more than 921,000 renter households in New York City, or 44 percent of all renters, pay at least 30 percent of their income in rent (the accepted definition of “rent burdened”). This is after accounting for the value of public assistance in rental housing vouchers and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits. More than half of these households—greater than 462,000 families and single adults—are considered severely rent burdened, defined as paying at least half of their income in rent.

To put those numbers in perspective, the 921,000 rent burdened NYC households equate to approximately 2.2M people, a little bit more than the entire population of New Mexico; the 462,000 severely rent burdened NYC households translates to the entire population of Rhode Island.

The pandemic has had a crushing impact on this same burdened population. It should be no surprise that there has been a spike in overcrowding, homelessness, and associated maladies. Homelessness is at a level not seen since the Great Depression. As of September 2021, approximately 48,000 people are sleeping in city shelters, including over 10,000 families, 4,300 single women, and 14,000 single men, according to the Coalition for the Homeless. These figures do not include the tragic number of people who are living on the streets.

New York City is not alone. Major cities have all seen similar trends.

In response, there is a growing recognition that access to high-quality, safe, and affordable housing is a basic right—and that it is in the best interest of society to insure the availability of affordable housing. After decades of disinvestment, a renewed focus on subsidized housing is generating political will for impactful housing investments by the federal government. Complimenting this federal-level initiative, some states and municipalities are reforming their land use regulations to encourage greater housing density; California and the city of Minneapolis have recently outlawed single-family zoning.

To address the need for affordable housing in the suburbs and in less-dense cities, much attention has been focused on accessory dwelling units (ADUs) and the “missing middle”—that scale of building between detached houses and elevator-type mid-rise buildings. In contrast, this article identifies strategies for transit-rich, “inner ring” neighborhoods with multi-family, mid- and high-rise housing—in other words, the buildings typically associated with “affordable housing projects.”

Old Paradigm

The degradation from the idealistic European social housing models of the 1920s (Ville Radieuse, Weissenhof Siedlungen) to the American large-scale production of the '50s and '60s (e.g., Pruitt-Igoe and Cabrini Green)—tainted with racial engineering and profiteering—is well-documented. In North America, the resulting large public housing “projects,” which employed “towers-in-the-park” planning on isolated campuses, are now widely discredited.

These complexes are separated from the physical and cultural fabric of the surrounding city. They are unimaginative and substandard—in effect, warehouses for concentrations of poor families. To add insult to injury, they have been the target of a systematic, generation-long disinvestment, becoming cynical proof of the dysfunction of government. The New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) campuses alone require a staggering $40 billion to bring them to state of good repair.

The resulting “bright lines” separating these communities from the rest of society lead to a stigmatization and dehumanization of the populations they are supposed to shelter and nurture.

New Paradigm

Vital Communities is a growing model of development that strengthens communities and gives individuals and families the support needed to thrive in connected, imaginative, resilient, and low-carbon environments. At its core, Vital Communities rejects the monoculture of the old paradigm by creating social housing that is a natural extension and infilling of our cities. Accordingly, public infrastructure, transit, civic institutions, and private amenities are as equally available to lower-income families as they are to wealthier residents. This interconnectedness is coupled with exemplary, varied, and sustainable design.

New social housing on the Vital Communities model operates at all scales of city building. In New York City especially, there is a growing body of examples, from individual buildings to multi-building developments and revitalized campuses.

Stand-Alone, Inclusionary Buildings: As part of its noteworthy record on housing, the De Blasio administration financed the construction of more than 50,000 new affordable homes. Of these, over three quarters were created by for-profit developers in mixed-income buildings. One such example is the Gotham Organization’s 550 Tenth Avenue (fig 1), which leveraged the value of cross-subsidization and tax incentives to deliver 456 residences, of which 114 are affordable.

The land was purchased from Covenant House, which used the proceeds to develop a new state-of-the-art homeless shelter (fig 2) on the remaining portion of the site. While some housing advocates are concerned that the tax abatements undergirding this type of development are overly generous, the mixed-income aspect achieves the elusive goal of inclusion. In a New York Times article titled “Living the Mix,” a tenant paying affordable rent in an inclusionary apartment building noted that “it has changed my life… I can’t believe that I am there, that at 23 with my own place. I always thought that I would live good, but just not this soon.”

Individual Affordable Buildings: When there is the opportunity to create a 100% affordable development, it is critical that it be part of a larger mixed-use development and in a central location. Radson Development’s 495 Eleventh Avenue (fig 3) in Manhattan’s Hudson Yards implements a blended strategy where for-profit elements of a hotel tower and supermarket podium cross-subsidize 350

affordable homes in a 63-story tower. With its elegant and sustainable design, the project avoids design tropes associated with “affordable housing." No distinction in quality is made between the hotel and residential towers; they are architectural partners.

Microneighborhoods: The possibilities for scale and amenities grow when several buildings are developed simultaneously and in coordination. At La Central in the South Bronx (fig 4), a consortium of developers (BRP Development Corporation, Hudson Companies, ELH-TKC, Breaking Ground, Comunilife, and the YMCA) orchestrated a vibrant, mixed-income, mixed-use blend, with a total of 992 units of affordable housing, including 160 units of supportive housing for formerly homeless veterans and New Yorkers living with special needs. The community also includes a new YMCA, Bronxnet television studios, and a host of new retail, community, and recreation spaces. It is both seamlessly connected to the larger urban grid and has its own clear identity and central focus. Sustainability, active design, and healthy living come together with ample roof-top terraces and home gardens.

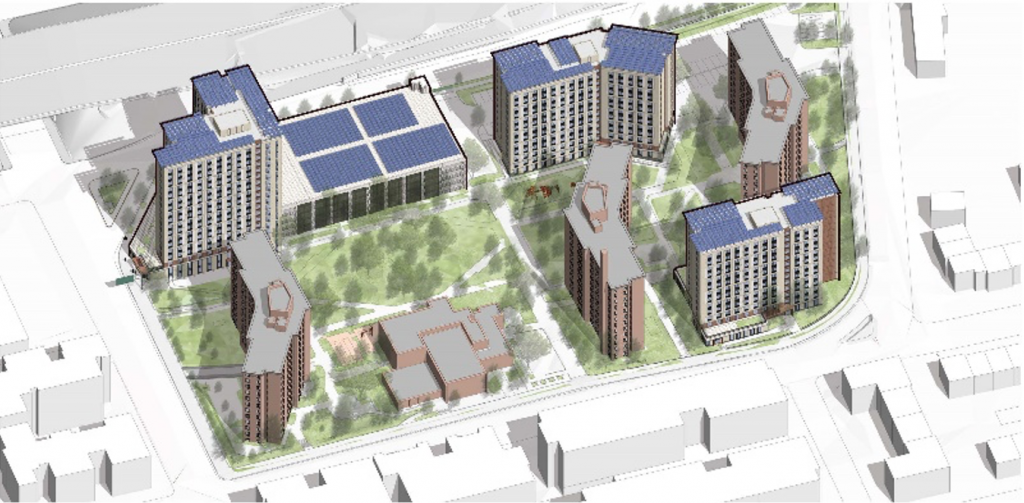

Reinvention of the Social Housing Campus: A critical need is to revitalize the many ailing post-war housing “projects.” When reimagining and densifying these developments, they can be woven back into surrounding neighborhoods and infused with civic infrastructure, including well-formed open space and healthcare, daycare, and community centers. At Phipps Houses’ Apex Place, a master plan elevates a former NYCHA development in Forest Hills, Queens into a cohesive and vibrant mixed-use community of residential towers, community facilities, and green spaces (figs 5 and 6). Three new buildings are inserted into left-over areas of an existing, 1970’s tower-in-the-park style campus. With the new buildings at the perimeter, the project has a more direct relationship with its neighbors. For the campus itself, the design creates more coherent and defined open spaces.

Apex Place will provide new housing for middle-income households, including 442 affordable units, medical offices, an expansion of existing community facilities, and a parking structure screened by greenery. The new structures are oriented for solar efficiency, while rooftop photovoltaic (PV) arrays on the new buildings provide an economic, sustainable, and attractive amenity for the development.

A Prescription for Policymakers

The Vital Communities approach can be expanded in New York City and exported as a model to other cities.

To that end, policies that encourage housing quality and connectivity should:

- Erase the bright lines: Encourage and incentivize inclusionary housing development in both rental and ownership models. Strive for a mix of incomes, uses, and typologies.

- Target central sites: Focus on under-developed or under-zoned sites in transit- and amenity-rich locations to create individual buildings and microneighborhoods.

- Reinvent existing campuses: Encourage and incentivize densification of towers-in-the-park legacy developments to benefit new and existing tenants.

- Build for the long haul: Housing production should be imaginative, resilient, and sustainable.

An energetic and sustained application of Vital Communities that embodies connectivity and quality will go far in promoting social interconnection and equality.

Dan Kaplan, FAIA, LEED AP, is a senior partner at FXCollaborative, a New York City-based architecture, interiors, and planning design firm. Dan serves in a design and leadership capacity for many of the firm’s complex, award-winning projects. Adept at creating large-scale, high-performance buildings and urban designs, he approaches each project with the mission that it must elevate and resonate with the larger urban, cultural, and climactic totality. Notable projects include 1 Willoughby Square (Brooklyn, New York), Allianz Tower (Istanbul, Turkey), Eleven Times Square (Manhattan, New York), and Fubon Financial Center (Fuzhou, China). Dan holds a Bachelor of Architecture from Cornell University and is a registered architect in numerous U.S. states.

Study: Maui’s Plan to Convert Vacation Rentals to Long-Term Housing Could Cause Nearly $1 Billion Economic Loss

The plan would reduce visitor accommodation by 25,% resulting in 1,900 jobs lost.

North Texas Transit Leaders Tout Benefits of TOD for Growing Region

At a summit focused on transit-oriented development, policymakers discussed how North Texas’ expanded light rail system can serve as a tool for economic growth.

Using Old Oil and Gas Wells for Green Energy Storage

Penn State researchers have found that repurposing abandoned oil and gas wells for geothermal-assisted compressed-air energy storage can boost efficiency, reduce environmental risks, and support clean energy and job transitions.

Santa Barbara Could Build Housing on County Land

County supervisors moved forward a proposal to build workforce housing on two county-owned parcels.

San Mateo Formally Opposes Freeway Project

The city council will send a letter to Caltrans urging the agency to reconsider a plan to expand the 101 through the city of San Mateo.

A Bronx Community Fights to Have its Voice Heard

After organizing and giving input for decades, the community around the Kingsbridge Armory might actually see it redeveloped — and they want to continue to have a say in how it goes.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Ascent Environmental

Borough of Carlisle

Institute for Housing and Urban Development Studies (IHS)

City of Grandview

Harvard GSD Executive Education

Toledo-Lucas County Plan Commissions

Salt Lake City

NYU Wagner Graduate School of Public Service