City Profiles

Explore cities through an urban planning lens.

Atlanta: An Urban Planner's Guide to the City

The nation’s first majority-Black city, Atlanta, has a rich identity steeped in African American culture and a sprawling footprint shaped by a complex history of the enterprising ‘Atlanta spirit,’ race relations, and segregation.

Basics about Atlanta

- State: Georgia

- Incorporation date: December 29, 1847

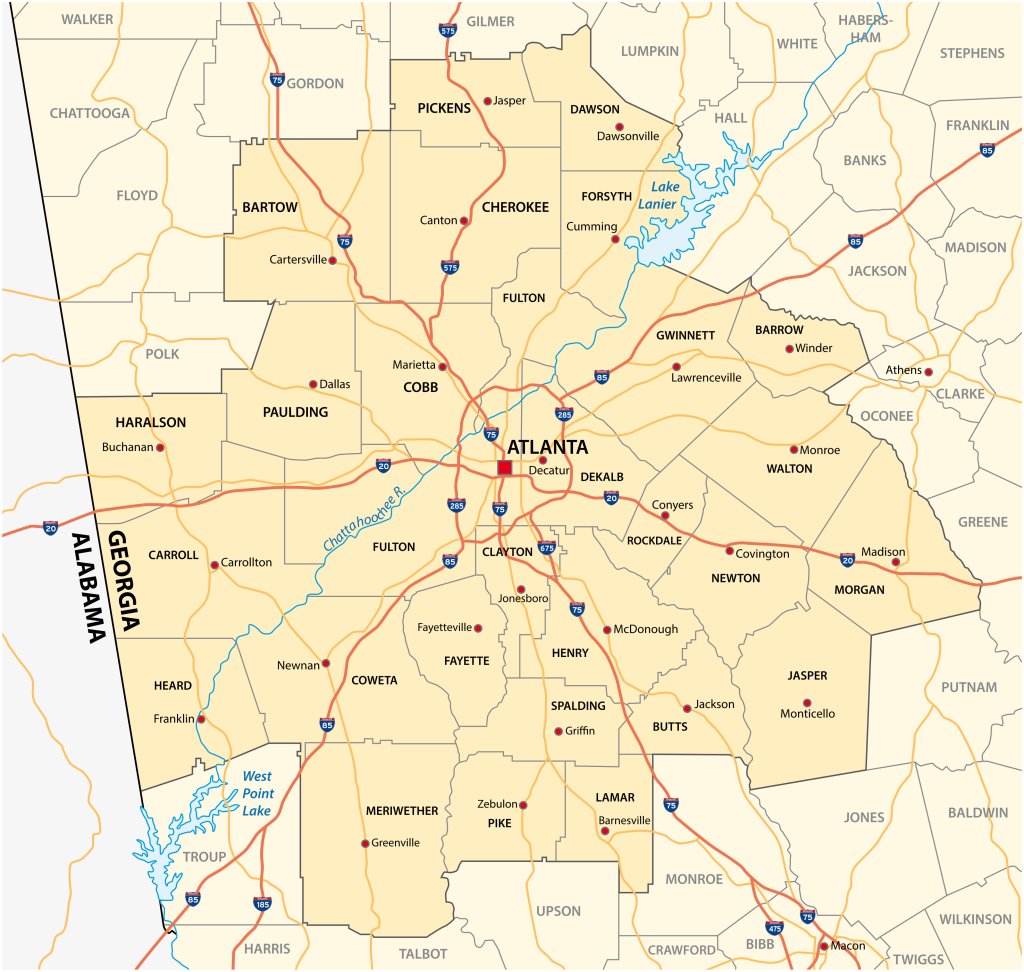

- Area: 132 sq mi (city), 8,376 sq mi (metro area)

- Statehood: January 2, 1788

- Population*: 498,715 (city), 6 million (metro area)

- Type of government: Strong mayor-council

- Planning department website: Atlanta Department of City Planning

- Comprehensive plan: City of Atlanta 2021 Comprehensive Development Plan Downtown Atlanta Master Plan; Fulton County 2035 Comprehensive Plan

*Current as of 2020 Census.

Atlanta’s indigenous peoples

Atlanta lies in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains in the northwestern part of what is now the state of Georgia. Earliest human habitation within the region is thought to date all the way back to 15,000 BC. The land that now makes up Atlanta was home to the Woodland and Mississippian peoples. Later it became the territory of the Cherokee and Muscogee peoples. The Muscogee Nation was made up of several groups and spoke a number of different languages, including Algonquin, Muskogean, and Siouan. Earthen mounds played important ceremonial roles in several of the areas’ indigenous groups, and many of those mounds remain in place today.

After the end of the Revolutionary War, most of Georgia was still Native American territory. But a series of treaties with the United States government over several years, starting in 1812, left the Muscogee nation entirely disenfranchised of millions of acres of their ancestral land. In the 1830s, they and other indigenous peoples from the region including the Cherokee were forcibly driven off their lands by white settlers. In 1837, federal soldiers rounded up the remaining indigenous people in the region and forced them on a cruel, deadly 8,000 mile journey West known as the Trail of Tears. Today there are no federally recognized Indigenous tribes in Georgia.

Colonization, the Civil War, and the spirit of the ‘New South’

In 1732, Georgia became the thirteenth, and last, British colony founded.

It was ratified as a state in 1788, four years after the end of the Revolutionary War. By the 1830s, around the time the indigenous people were being forced from the lands, railroad lines were being extended into Georgia's interior, which was key to Atlanta’s rapid growth. In fact, the city of Atlanta was founded in 1837 (originally called Marthasville), the same year as the Trail of Tears, as the end of the Western & Atlantic railroad line. The city was officially incorporated and rechristened Atlanta ten years later. By 1860, it had become the fourth largest in the state with a population of around 9,500. At that time, one in five Atlanta residents were Black slaves, and across the state’s 1 million residents, 56 percent were white and 44 percent were Black (99.7 percent of whom were enslaved).

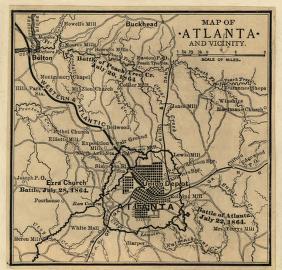

Then came a turning point for the city and the country as a whole. In 1861, Georgia seceded and joined the side of the Confederacy in the Civil War, during which Atlanta played a vital role in the production, distribution and transport of munitions and supplies. The city fell to the Union Army in the Battle of Atlanta in 1864, after which a significant portion of the city was burned and the railroad lines torn up to keep them from benefiting the Confederate Army.

“Despite these austere conditions, Atlanta emerged from the ashes to rebuild quickly,” according to an article from the New Georgia Encyclopedia. In a little over a year, all the city’s rail lines were again operational, and within two years, the city’s population grew by nearly 20,000 people. Atlanta’s position at the southern extremity of the Appalachian Mountains made it a critical gateway for shipping and travel between the southern Atlantic Seaboard and the burgeoning West. By the turn of the century, fifteen rail lines passed through the city, with more than 150 trains arriving in Atlanta every day. According to an article on Britannica.com, “During this time, Atlanta came to epitomize what was considered the spirit of the ‘New South,’ having risen from the ashes of the Civil War and become an advocate of reconciliation with the North in order to restore business,” driven by industry and less on agriculture. During this time the city developed robust educational institutions, including the Georgia Institute of Technology, Oglethorpe University, Agnes Scott College, and black colleges including the first historically black college in the Southern U.S.

20th century growth: a story of transportation and segregation

The New Georgia Encyclopedia puts it best: “The three dominant forces affecting Atlanta’s history and development have been transportation, race relations, and the ‘Atlanta spirit.’ At each stage in the city’s development, these three elements have come into play.” This was clearly reflected in the 18th century, with the growth of the railroads, the dynamics between the area’s indigenous people and the early British settlers and American government, as well as during the Civil War and its aftermath. And it’s equally, if not more true, of the city’s evolution in the 20th century, which laid the groundwork for the city as we know it today.

Atlanta continued to thrive as a regional transportation hub, thanks to its geographical position just south of the Blue Ridge Mountains, which made it a key rail gateway to the West. The 1920s ushered in the era of automobiles and road networks, as well as Atlanta’s first airport in 1929 (later Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport) — both of which expanded exponentially over the next several decades and earned Atlanta the moniker of “transportation capital of the Southeast.” Public transit joined the mix in the 1960s with the creation of the Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority, which took over the city’s bus systems and built a light rail system with four service lines.

Throughout the 20th century, city leaders worked hard to make Atlanta a center of business, commerce, finance, and education, which shaped the city’s downtown and skyline. Over the course of the century, Atlanta’s population increased from 90,000 to 400,000 and became the first majority black city in the U.S. in 1970. Seen as “Black Mecca” because of its job and educational opportunities for its Black residents, Atlanta drew African Americans from across the country after the Civil War and beyond. This demographic trend played a huge role in shaping not only Atlanta’s culture, but also its built environment, governance, and economies.

Racism, Jim Crow ordinances, and Urban Renewal era freeways led to a highly segregated city. Black neighborhoods were concentrated to small areas of the city and received less investment in infrastructure, public services, and green space like parks. There was significant racial tension and hostility between white and Black Atlantans that often led to violence; the Klu Klux Klan made Atlanta its headquarters in 1915 and still has a presence in the city today. “Despite these restrictions, the presence of this strong nucleus of Black colleges and growing economic opportunities laid the foundation for an emerging and influential Black middle class,” according to the New Georgia Encyclopedia. Auburn Avenue, the birthplace of Martin Luther King, Jr., and the neighborhoods around it emerged as one of the most important areas in the city for Black Atlantans.

The geographical segregation and disinvestment in Black neighborhoods intensified after WWII with the acceleration of white flight from the city to the suburbs. The rapid development of these suburban neighborhoods exacerbated sprawl and new and expanded freeways, which led to widespread automobile, poor air quality, and displaced poor and Black neighborhoods. Following the Civil Rights movement, the stark lines between white and Black neighborhoods started to crumble, opening up new areas of the city for Black residential development. As a result, the exodus of white Atlantans increased further, resulting in a majority Black Atlanta between 1970 and 2020.

In the latter half of the 20th century, the city undertook several efforts to reconcile the wrongs of the urban renewal period by building new public facilities and low-income housing to replace homes lost during highway construction. It also renewed its economic development efforts, attracting major sports teams the Braves and the Falcons; high-profile businesses like Coca-Cola, CNN, and the United Postal Service; as well as foreign companies, consultants, and trade offices. It also hosted the 1996 centennial summer Olympic Games, which “contributed to the construction and improvement of many public buildings and facilities in downtown Atlanta, including the Olympic Stadium (which became Turner Field) and the twenty-one-acre Centennial Olympic Park. The Olympic Village housing was converted to student housing for Georgia Tech and Georgia State University (GSU); in 2007 GSU transferred ownership of its portion of the former village to Georgia Tech,” according to the New Georgia Encyclopedia.

21st century concerns: traffic, displacement, and post-pandemic revitalization

Today, Atlanta is one of the nation’s most important network of rail lines, interstate highways, and air travel, as well as the sixth largest and one of the fastest-growing metropolitan areas in the U.S. As of the 2020 Census, the Atlanta metro population was 6 million — that’s 56 percent of the entire state population — and another 1.8 million people are expected by 2050. While that’s a win from an economic standpoint, the continued rapid growth will put significant pressure on one of the city’s largest and possibly most frustrating challenges for residents and visitors alike: traffic. Spread across more than 20 counties and 8,376 square miles, the region has a lot of roads, millions of cars, and a reputation for having the worst traffic in the country. Unfortunately, in large part due to suburban counties’ resistance to expansion of rail and bus lines into their jurisdictions, MARTA has not fulfilled its original vision of reducing the city’s dependence on cars.

In terms of demographics and neighborhood makeup, the sharp racial divide has softened somewhat as more Black residents move to the suburbs and and more white residents move back into the city. But the patterns of segregation are still clear, as are the stark differences in income between city and suburban residents, and the huge disparity in public amenities like parks and other green space. In the early 2000s, the city, as part of a public-private-nonprofit partnership, undertook an ambitious project to reconnect historically marginalized and underserved Black neighborhoods in the city’s urban core. The Atlanta Beltline is an ambitious 22-mile loop of multi-use trail and light-rail transit built along an old railway corridor. The first segment opened in 2008, and it is scheduled for completion by 2030. While the project is much celebrated and has brought much-needed amenities and development to the adjacent neighborhoods, the influx of higher-income residents it has attracted has raised longtime residents’ fears of displacement as rents and property taxes rise.

The COVID pandemic also threw a spanner in the city’s efforts to boost its convention and tourism business. For two decades, the city invested a lot of money into downtown, including an expansion of the World Congress Center, and the construction of sports facilities—Turner Field for the Braves, the Georgia Dome for the Falcons, and State Farm Arena — was well as additions to the downtown entertainment and convention district, including the Children’s Museum of Atlanta; the Georgia Aquarium, the largest in the U.S.; an enlarged World Coca-Cola museum; the National Center for Civil and Human Rights; and the College Football Hall of Fame. But tourism and downtown visitor traffic plummeted during the pandemic and has been slow to recover. Some city leaders are calling for renewed revitalization efforts, including safety and green space improvements to draw people downtown again, particularly in advance of the expected hundreds of thousands expected to attend major upcoming events like the College Football Playoff National Championship in 2025 and eight matches of the FIFA World Cup 2026.

Key planning milestones for Atlanta

- 1837: Atlanta was founded as Marthasville, and the last of the indigenous people were forced from the state on the Trail of Tears.

- 1847: The city was officially incorporated and renamed Atlanta.

- 1920: The Atlanta Department of Planning Commission was created.

- 1935: The first public housing project in the U.S. — Techwood Homes — opened. It was restricted to white people only.

- 1938: City’s first public housing project for African Americans — University Homes — opened.

- 1950: Georgia Tech (founded in 1885) created a graduate city planning program.

- 1952: Atlanta and Fulton counties consolidated their planning departments to create the Department of Municipal Planning, which has changed names five times since.

- 1962: Courts ordered the removal of city barricades along Peyton Road in southwest Atlanta, the mayor ordered erected to prevent Black residential expansion into majority white neighborhoods.

- 1965: The Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority (MARTA) Act passed.

- 1968-69: Underground Atlanta, a subterranean complex of shops, bars, and cafés on the original street level of the city, was declared a historic site and opened as an entertainment district.

- 1971: Voters approved funding for the Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority (MARTA).

- 1973: Atlanta became the first major city in the South to elect an African American mayor, Maynard Jackson.

- 1972: MARTA purchased the Atlanta Transit System, gaining complete control over Atlanta’s main bus system.

- 1979: Atlanta’s first mass-transit rail line opened.

- 1996: Atlanta hosted the centennial summer Olympic Games, which contributed to the construction and improvement of many public buildings and facilities in downtown Atlanta, including the Olympic Stadium.

- 2005: The Beltline was officially launched with the approval of the Beltline Redevelopment Plan partners.

- 2014: Streetcars were reintroduced to the city.

- 2017: City planning department changes its name to the Department of Planning and Development.

Philadelphia Could Lose Free Transit Program

The city’s upcoming budget doesn’t include the Zero Fare program, which offers free SEPTA fare to more than 24,000 residents.

Community-Led Efforts to Combat Gentrification in Philadelphia’s University City

How residents came together to fight for housing equity.

Philadelphia Tests Bulletproof Enclosures for Bus Drivers in Wake of Fatal Shooting

The city is one of several aiming to improve driver safety.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Caltrans

Smith Gee Studio

Institute for Housing and Urban Development Studies (IHS)

City of Grandview

Harvard GSD Executive Education

Toledo-Lucas County Plan Commissions

Salt Lake City

NYU Wagner Graduate School of Public Service