An important current policy debate concerns whether the next U.S. federal surface transportation reauthorization should require spending on “enhancements,” which finance projects such as walkways, bike paths, highway landscaping and historic preservation. This issue receives considerable attention, despite the fact that enhancements represent less than 2% of total federal surface transportation expenditures, because it raises questions about future transport priorities, particularly the role of walking and cycling. In other words, should non-motorized modes be considered real transportation.

An important current policy debate concerns whether the next U.S. federal

surface transportation reauthorization should require spending on

"enhancements," which finance projects such as walkways, bike paths, highway landscaping and historic preservation. This issue

receives considerable attention, despite the fact that enhancements represent less

than 2% of total federal surface transportation expenditures, because it raises

questions about future transport priorities, particularly the role of walking and cycling. In other words, should non-motorized modes be considered real transportation.

Critics argue that enhancements projects are luxuries and it is unfair to divert

motor vehicle user fees to projects that do not directly benefit motorists. As Ronald Utt of the Reason Foundation wrote about enhancement funding categories, "Alert

readers will note that none of the above eligible uses supports transportation

in the modern sense of the term. Indeed, these 12 categories have as much to do

with transportation and mobility as G.I. Joe dolls have to do with national

security." According to that view, walking and cycling are not real transportation, at least, not in the "modern sense of the term," they are nothing more than children's entertainment. (I wonder if this perspective is shared by Reason Foundation fellow and

Planetizen Blogger, Samuel Staley, who recently described how he enjoys bicycle commuting. Any comments

Sam?) Let's examine these arguments.

Responsive Priorities

As described in a previous Column, travel demands are

changing. Total motor vehicle travel peaked in 2007 and is expected to remain

flat in most area (those not experiencing rapid population growth) due

to demographic and economic trends including aging population, rising

fuel prices, increasing health and environmental concerns, and changing

consumer preferences. This is not to suggest that North Americans will give up

driving altogether, but at the margin many people want to drive less and rely

more on alternatives, provided they are convenient, comfortable and

integrated. It makes sense for transport policies to respond to these demands by helping create a more diverse, resource-efficient transport

system.

Although federal funds provide only about 30%

total roadway expenditures, they have significant leverage effects on state

and local transport planning decisions. For example, if the federal government

offers attractive grants for highway projects, states and local

governments will plan to solve their transport problems with highway expansions. If more federal funding is provided for alternative modes, state and local officials will consider other

solutions.

Current planning tends to be biased in various, often subtle ways

that favor automobile transport over other modes. For example, conventional

travel surveys, and resulting travel statistics, tend to undercount

non-motorized travel because they overlook short trips, off-peak trips, travel

by children, and non-motorized links of linked trips. A bike-transit-walk trip

is often coded simply as a transit trip, and a motorist who parks several

blocks from work and walks is simply considered an auto commuter. Although

conventional travel surveys suggest that only 4-6% of trips are non-motorized,

more comprehensive surveys, such as the National

Household Travel Survey, indicate they are actually 10-15%, and even higher in large

cities. Non-motorized travel improvements receive far less than this portion of

funding: only

1.2% of total federal surface transport funds are spent on non-motorized

facilities, and although local governments probably devote a somewhat larger share of their transport budgets to sidewalks and paths, perhaps 3-6%, but that is still much less than the share of non-motorized trips.

Another bias is that transport system performance is

generally evaluated using mobility-oriented indicators, such as roadway

level-of-service, average traffic speed, and traffic congestion delays, which

assumes that the goal is to maximize vehicle travel speeds, so faster modes are

more important than slower modes. This approach tends to undervalue

non-motorized modes, and ignores the ways that planning decisions that improve

motorized travel often reduce non-motorized accessibility, for example, if

wider roads and increased travel speeds create a barrier to walking and

cycling, and if highway expansion and generous minimum parking requirements encourages

dispersed, automobile-oriented development that reduces land use accessibility.

For example, this type of planning considers the transport

system to fail if motorists encounter congestion (roadway level-of-serve D or

worse) when chauffeuring children to school, or driving to a gym to exercise on

a treadmill, or somebody drives to reach a recreational cycling path, but does not

recognize a failure if inadequate walking and cycling facilities prevent

students from walking and cycling to schools, or if residents are unable to walking or bicycle in their own neighborhoods. Fortunately, the new Highway Capacity Manual

includes guidance on multi-modal

level-of-service evaluation, but such reforms are inadequate without funding to improve walking and cycling conditions.

Most federal and state funds are dedicated to roads. About half of all states have constitutional amendments that dedicate road user fees to highways. Federal match rates tend to be higher for highways than for other modes, and highway projects often require less analysis and review than other transport investments.

Critics argue that non-motorized improvements, if justified,

are a local rather than a federal concern, but this ignores the large portion

of federal highway capacity used for local travel. As a result, the federal government helps accommodate

motorists driving children to school, driving to gyms or trails for exercise,

and numerous other local trips, some of which could instead be made by walking and

cycling if conditions were better.

Non-motorized Transport Benefits

Improved walking and cycling conditions, and increased

non-motorized travel activity can provide numerous benefits to users and

society, including congestion reductions, road and parking facility cost savings,

consumer savings and affordability, improved mobility for non-drivers, energy

conservation, pollution emission reductions, improved public fitness and health,

and local economic development. Total per capita accident rates (including both motorized and non-motorized road users) tend to decline as walking and cycling

rates increase in a community, an effect called safety in

numbers.

Even motorists who never walk or bicycle can benefit from such improvements. For

example, if you want your neighbor to avoid driving home after drinking at the

local bar, it's pretty important that he have good sidewalks. Improving walking

and cycling conditions reduces drivers' chauffeuring burdens.

Critics sometimes argue that only a small portion of travel

can reasonably shift to walking and cycling, or non-motorized improvements do

little to reduce problems such as traffic and parking congestion, but this

reflects an incomplete understanding of the role walking and cycling play in an

efficient transport system. Communities with good non-motorized facilities have

walking and cycling mode shares several times higher than the North American

average. Many of these additional non-motorized trips substitute for driving.

Improving walkability increases the parking facilities that serve a

destination, reducing parking congestion problems. Most public transit trips

include non-motorized links, and improving walking and cycling conditions is

often key to shifting travel from driving to public transit. A shorter

pedestrian or bicycle trip often substitutes for a longer motorized trip,

non-motorized travel improvements support more compact land use development,

and improving alternative modes allows some households to reduce their vehicle

ownership, so pedestrian and cycling improvements can leverage additional reductions

in automobile travel, so each mile increase in pedestrian and cycling travel

can provide more than vehicle-mile reduction in automobile travel.

Funding Equity

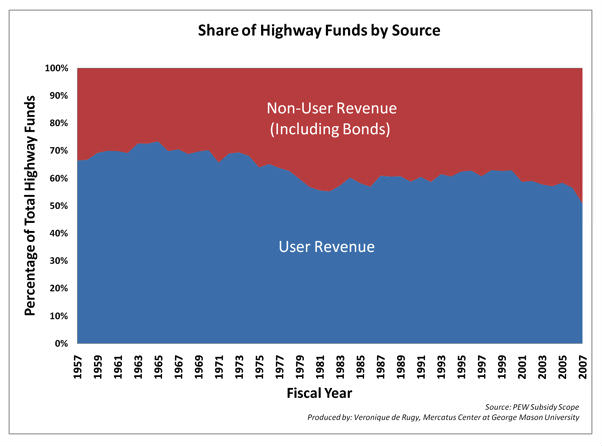

Enhancement critics argue that it is unfair to spend money

collected from motorists though fuel taxes and other user fees to finance other

modes, based on the assumption that consumers should "get what they

pay for and pay for what they get."

But this argument is hypocritical since the same logic also

demands that motorists should bear the full costs they impose. In fact, road user

fees finance less than half of total roadway expenditures, a portion that is

declining since fuel taxes have not increased to account for inflation. Walking and bicycling impose far lower (probably about 10%) road and parking costs than driving measured per mile, and non-drivers tend to travel far fewer annual miles than motorist on average. As a

result, people who rely primarily on walking and cycling for transport tend to subsidize the transport

costs of their neighbors who drive.

Total roadway expenditures per capita average about $400 annual per capita, about half from motorist user fees and half from general taxes. This is the amount an average traveler imposes and pays. A person who relies primarily on non-motorized travel pays $200 annually in general taxes but only imposes about $25 in roadway costs, and so pay $175 more than their costs. Conversely, a motorist who drives twice average mileage imposes $800 in roadway costs but only pays $600 in taxes, and so underpays.

Vehicle travel imposes other external

costs. There are typically three or

more off-street parking spaces provided per motor vehicle, with total value estimated at $1,000-2,000 annual per vehicle, and motor vehicle travel imposes significant accident and pollution costs on other road users, including pedestrians and cyclists. As a result, higher-annual-mileage motorists significantly underpay, and people who rely on alternative modes overpay their transport costs. This is unfair and economcially inefficient because it encourages people to drive more than they would choose if road users paid directly for the costs they impose.

Enhancements help mitigate the risks and problems that motor

vehicle travel imposes, for example by financing

pedestrian bridges over highways that divide neighborhoods, and paths that

separate pedestrians and cyclists from highway risk and pollution. In

other words, enhancements allow motorists to help clean up the mess they make.

As I've written

previously, automobile transportation is so costly that it tends to make users selfish. In an automobile

dependent community people are forced to drive even if it strains their budget.

They then argue, "I'm forced to spend thousands of dollars annually on a car just for

basic transportation, I can't possibly afford to pay more. I need a subsidy!" As a result, they become

upset when asked to pay the full costs of roads, parking and fuel, or to share resources with other modes. The smart solution to this problem is to improve alternatives so people have better, more affordable options.

That is exactly the value of Enhancements.

What do you think? Should federal support for non-motorized modes increase or decline in the future? What arguements do you find most persuasive in this debate?

For More Information

ABW (2010), Bicycling

and Walking in the U.S.: 2010 Benchmarking Report, Alliance for Biking

& Walking (www.peoplepoweredmovement.org);

at www.peoplepoweredmovement.org/site/index.php/site/memberservices/C529.

Joe Cortright (2009),

Walking the Walk: How Walkability Raises

Home Values in U.S. Cities, CEOs for Cities (www.ceosforcities.org); at www.ceosforcities.org/files/WalkingTheWalk_CEOsforCities1.pdf.

FIA – UNEP (2011), Share the Road: Investment in Walking

and Cycling Road Infrastructure,

FIA Foundation for Automobiles and Society and the United Nations Environmental

Program (http://www.unep.org); at http://www.unep.org/transport/sharetheroad/PDF/SharetheRoadReportweb.pdf.

Fietsberaad (2009), Cycling in

the Netherlands, Ministry of Transport, Public Works and Water Management (www.minvenw.nl) and Fietsberaad (Expertise Centre for Cycling

Policy) (www.bicyclecouncil.org); at www.fietsberaad.nl/library/repository/bestanden/CyclingintheNetherlands2009.pdf.

LAB (2010), Highlights

the 2009 National Household Travel Survey, League of American Bicyclists (www.bikeleague.org);

at www.bikeleague.org/resources/reports/pdfs/nhts09.pdf.

Todd Litman (2003), "Economic Value of Walkability," Transportation

Research Record 1828, Transportation Research Board (www.trb.org), pp. 3-11; at www.vtpi.org/walkability.pdf.

Todd Litman (2005), Whose Roads? Evaluating Bicyclists' and

Pedestrians' Right to Use Public Roadways, VTPI (www.vtpi.org); at www.vtpi.org/whoserd.pdf.

Todd Litman (2010), Short

and Sweet: Analysis of Shorter Trips Using National Personal Travel Survey Data,

VTPI (www.vtpi.org); at www.vtpi.org/short_sweet.pdf.

Todd Litman (2011), Evaluating

Non-Motorized Transport Benefits and Costs, Victoria Transport Policy

Institute (www.vtpi.org); at www.vtpi.org/nmt-tdm.pdf; originally

published as "Quantifying Bicycling Benefits for Achieving TDM Objectives," Transportation Research Record 1441,

Transportation Research Board (www.trb.org),

1994, pp. 134-140.

Living Streets (2011), Making

The Case For Investment In The Walking Environment, Living Streets Program

(www.livingstreets.org.uk),

University of the West of England and Cavill Associates; at www.livingstreets.org.uk/index.php/tools/required/files/download?fID=1668.

NHTS (2010), Active

Travel: NHTS Brief, National Household Travel Survey (http://nhts.ornl.gov); at http://nhts.ornl.gov/briefs/ActiveTravel.pdf.

S. Turner, R. Singh,

P. Quinn and T. Allatt (2011), Benefits Of New And Improved Pedestrian

Facilities – Before And After Studies, Research Report 436, NZ Transport

Agency (www.nzta.govt.nz); at www.nzta.govt.nz/resources/research/reports/436/docs/436.pdf.

Alabama: Trump Terminates Settlements for Black Communities Harmed By Raw Sewage

Trump deemed the landmark civil rights agreement “illegal DEI and environmental justice policy.”

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Why Should We Subsidize Public Transportation?

Many public transit agencies face financial stress due to rising costs, declining fare revenue, and declining subsidies. Transit advocates must provide a strong business case for increasing public transit funding.

Understanding Road Diets

An explainer from Momentum highlights the advantages of reducing vehicle lanes in favor of more bike, transit, and pedestrian infrastructure.

New California Law Regulates Warehouse Pollution

A new law tightens building and emissions regulations for large distribution warehouses to mitigate air pollution and traffic in surrounding communities.

Phoenix Announces Opening Date for Light Rail Extension

The South Central extension will connect South Phoenix to downtown and other major hubs starting on June 7.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Caltrans

Smith Gee Studio

Institute for Housing and Urban Development Studies (IHS)

City of Grandview

Harvard GSD Executive Education

Toledo-Lucas County Plan Commissions

Salt Lake City

NYU Wagner Graduate School of Public Service