Are skyscrapers the way to achieve great density, or a form of retro-urbanism that should be retired? With a debate simmering in the planning world over the energy efficiency and urban necessity of tall towers, Planetizen's staff decided to determine the answer once and for all.

The current debate on the sustainability of skyscrapers and their proper place in today's urban environments has great implications for the future of city-building. On the one hand, some urban thinkers foresee a 21st century defined by ultra-dense Skyscraper Cities, while other urbanists like James Howard Kunstler would describe such vision as "yesterday's tomorrow." Either way, the awe and imagination inspired by mega-structures are hard to deny. Daniel Burnham's Flatiron Building from 1902 and Cook+Fox Architects' Bank of America Tower in 2009 represent over a century of advancement in engineering prowess, architectural might, and more recently, concern for the Earth's limited resources.

The jury is still out, however, on skyscrapers. Are very tall buildings a sustainable model for development suitable for a future of withering resources? And to the extent that dense, mixed-use developments and vibrant streetscapes are becoming the preferred model, are skyscrapers good urbanism?

We proceeded to explore these questions with a belief that simple comparisons between the energy consumption of low- and high-rise buildings would lead to a definitive answer. In the process, we looked at a number of variables, including the heating and cooling system, elevator use, and LEED certification criteria, that would more or less influence a building's total energy expenditure. What we discovered is that the question of energy consumption - for promoters as well as detractors - is not the primary topic of debate. The issues are instead more nuanced, including the "embodied energy" of the materials used in construction, the life of the building as well as the need for future rehabilitation and the proximity to urban amenities.

We interviewed some of the nation's leading architects, engineers, environmentalists, and urban commentators. While each individual brought a unique perspective to the conversation on the place of skyscrapers in contemporary cities, they mostly agreed on one thing. That is, in the words of James Howard Kunstler, "It's completely self-evident that you do not require mega-structures to have a successful city."

Energy Use

"The energy issues may be the least of the problems, although not unimportant."

As the prophet of peak oil and declining energy access, it was a surprise to hear these words from Kunstler. In the past, he has painted images of energy outages stranding people on the 25th floor of a skyscraper, and making life unbearable when heating and cooling can't be supplied and the windows won't open. "Skyscrapers will be obsolete, travel greatly reduced, and the rural edge more distinct. The energy inputs to our economies will decrease a lot, and probably in ways that prove destabilizing," he writes in a recent Orion magazine article aptly titled "Back to the Future."

Today, while he still very much believes that skyscrapers are not ideal, Kuntsler is slightly more circumspect on the energy argument, focusing instead on the problem of maintaining and renovating these glass towers. Kunstler argues that materials like manufactured sheet-rock, silicon gaskets and sealers that hold glass curtain walls in place are products of our cheap oil economy.

Bank of America Tower at One Bryant Park from Cook+Fox Architects on Vimeo.

Professionals working closer to the business of building these behemoths have different perspectives. Serge Appel, the lead architect at Cook+Fox Architects, says there is no significant difference in energy demand for the heating/cooling system of high- and low-rise structures. Appel designed the 54-story Bank of America Tower at One Bryant Park, the first high-rise of its kind to receive the LEED-Platinum designation.

"If you're comparing the high-rise to the low-rise, heating and cooling is effectively the same thing. You take the same amount of energy to heat a space and cool a space [whether] it's 900 feet up in the air or ten feet up in the air," says Appel. "That doesn't make a difference."

How you get to those floors may have an impact, however. Added floors mean added elevators and more energy consumption. How much more energy?

"Taller buildings require faster and bigger elevators, which means higher energy consumption. It can be up to 10-15% in super tall buildings," says Luke Leung, director of Sustainable Engineering Studio at Skidmore, Owings and Merrill (SOM).

But the energy use of elevator systems has reduced significantly in the past 25 years, and accounts today for only five percent of a building's energy use, according to Brian Black, code and safety consultant for the National Elevator Association, Inc. "Elevators have made our current, urban environment possible and have done so with a efficiency, and cost (effectiveness)," says Black.

Today, sophisticated software can reduce an elevator's energy use by calculating the most efficient way a person can reach his or her destination. When a rider selects a floor, a destination dispatch system sends down specific cars to best serve the multiple riders. This type of system lessens the number of rides and allows more elevator cars to be filled more often than cars with a single occupancy, just like the systems that airlines now use to make sure their planes fly full.

Yet even though the technology is available, that doesn't mean a building owner will invest in the greener option, says Black. Still, it is clear that today's green buildings have less significant energy issues than the skyscrapers of the past.

Refurbishing and Materials

So what of Kunstler's concern that skyscrapers will degrade as resources become more scarce? Appel explained to us how consideration went into how parts of the Bank of America Tower could be accessed when it need refurbishing or upgrades. The location of the under-floor air distribution system was installed to allow easy access to clean and maintain it, and the major chillers were placed below the loading dock where the units could be pulled out in one piece.

"Certain aspects of the building were designed with change over time in mind," Appel said. "It all depends [on] what kind of refurbishing is envisioned, how well it was maintained over its lifespan, and if there had been any upgrades over that time."

Predicting the life expectancy of a building is more vague. Brenden McEneaney, a Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) Accredited Professional, says that the lifespan of a building does not play a factor in the LEED accreditation process.

Currently, LEED only offers credit for companies that perform a life cycle analysis, an analysis for making material choices that looks at the life cycle of a material from extraction to installation. "There's a really big grey area on materials," McEneaney says. "A lot of materials we don't have a handle on yet."

LEED is currently working on revising its accreditation rules to make the life cycle analysis a requirement, more than likely in the design and construction stages, says McEneaney.

Aside from prohibiting materials that would have negative health effects, the overall environmental impact of using certain materials such as rare metals is still being determined by the U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC), the organization that determines the LEED criteria.

Appel explained that there is significantly more awareness on the materials that go into the construction of buildings these days. "Whenever possible, materials are more recyclable or coming from recycled sources." he said. "And we try to sort materials much closer to the location where the building is going to be built so that we don't have to truck things from half way around the world."

Urbanism and Skyscrapers

Perhaps more than energy use, the jury is out on whether skyscrapers are good urbanism. Planners and New Urbanists are of course focused on the street-level experience, and can be suspicious of skyscrapers because often the postwar versions fail to meet the street in an effective way. Many contemporary or modern skyscrapers are part and parcel of the same bad strategies that emptied out downtowns and created bad pedestrian environments.

On the other hand, taller buildings provide an opportunity for higher density, and density is music to the ears of planners because it creates environments where people walk more, take transit and make better use of infrastructure. Appel's Bank of America Tower, for example, is located near a variety of restaurants, is well-serviced by public transportation (at least two subway stations are located within a half-mile radius), and the building's ground level was designed to be an "indoor extension" of Bryant Park.

"Transportation is the critical thing," says Appel. "It's all about how people get to buildings," he said. "And a bigger building on a small site you can take advantage of a lot of things that you can't on a small building on a big site."

Brent Toderian, planning director of Vancouver, B.C., agrees. "When thinking about building energy, remember location, location, location." he says. "You shouldn't separate building design from location and transportation energy. A very green tower that's car-oriented isn't really green."

So with excellent transportation and location a given, can we make a blanket statement on skyscrapers as good urbanism, vs., say, the density of Madrid, with 5-story mixed-use buildings filling every block?

Edward Glaeser, a professor of economics at Harvard and the author of Triumph of the City, makes a classic supply and demand argument in favor of skyscrapers: in certain highly desirable places (Manhattan, Hong Kong, etc.) skyscrapers create a greater supply of living space on land for which there is significant demand. In fact, Glaeser wrote an article in The Atlantic titled, "How Skyscrapers Can Save the City."

That is not to say, however, that he sees skyscrapers as a necessity in every urban context. On the contrary, when asked about the proper place of skyscrapers in today's cities, Glaeser responded:

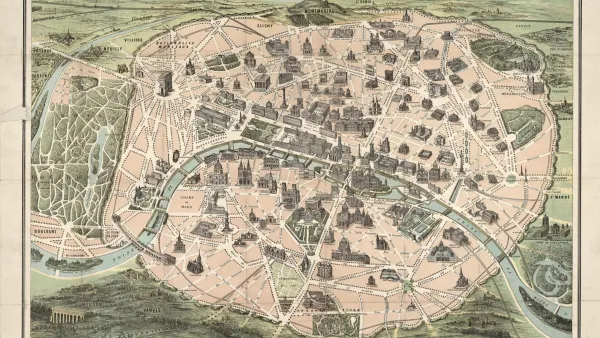

"I don't think there is any evidence that suggests that skyscrapers are profoundly deleterious [to cities]. I don't think they destroy urban spaces when properly done. We have lots of wonderful, vibrant cities with plenty of skyscrapers like New York or Hong Kong. I don't think the new height that Boston has added has done any harm to Boston. The city feels much less sleepy and far more exciting than it did 20 years ago. On the other hand, it's certainly possible to have vibrant, wonderful, urban spaces without skyscrapers. Greenwich Village being one; Paris being another.

"It's not so much that I am advocating for skyscrapers," continues Glaeser. "I am advocating against the barriers that make it impossible to build them in highly desirable areas. The cost of those barriers is that you're saying 'no' to people that want to live in a great urban space. Obviously, the answer is not to tear up all of Paris and replace it all with anonymous skyscrapers, but not every spot in Paris is really sacred."

What Goes Up, Must Come Down

Kunstler, on the other hand, sees the economic viability of skyscrapers to be the Achilles Heel of the entire venture. As he explains it, the collective ownership of large apartment buildings through condos organized as homeowner associations, or HOAs, could be an increasing problem as the economy shrinks. "What I think we are going to see are the failures of the homeowners' associations as capital becomes scarce and people who own units in mega-structures get into trouble with their finances and you start to get foreclosures and defaults," he explains. "I don't think we're yet at the half way point of this unravelling of finance, and as it increases and gets more severe we're going to start to see it in the inability of homeowners' associations to care for these buildings under the current model."

"Like many things Jim says, I think there's a grain of truth there combined with an overstatement," responds Brent Toderian. As planning director of Vancouver, Toderian has overseen a significant development boom in the city's downtown core with a unique strategy for building towers and townhouses on the same parcel, essentially combining the two forms.

"I think that buildings and condo structures are going to have to consider sustainability and resiliency in the long term, and many haven't," he explains. "But to suggest that the form is fundamentally nonviable because of that I think is a significant overstatement."

Rowhouse podium housing in Vancouver, B.C.

Keeping Skyscrapers in Perspective

"When it comes to form in a city, its not "either/or", its "yes, and..."

Toderian, interviewed at the end of our research, in many ways blew our central argument out of the water. With energy use no longer a serious problem because of newer green techniques, and a growing awareness of streetscaping and the necessity to foster urban life, why not allow height as part of your city's toolbox?

"Towers often get a bad reputation based on how they land and often that's true. But I just as often see mid-rise buildings land poorly," said Toderian. "This isn't the tower vs. mid-rise issue, this is the how you do the ground plane well, a universal question no matter what form you're designing."

The trick, he explained, is to be very rigorous with urban design standards and planning out the where, why and how of siting skyscrapers. "We likely take more of a design approach to the height question than any other city in North America, and we regulate, locate, shape and even limit height more than other cities, based on our civic values and goals," he explained.

So what are the civic values and goals of our cities? Perhaps the problem lies in a lack of a clear, agreed-upon vision for the future. Skyscrapers will always be iconic symbols of economic hopefulness: perhaps in some cases, that hopefulness is overreaching, and driven by profit motives rather than common sense and urbanism. We can only conclude that the evidence suggests that energy use is no longer a significant differential when comparing skyscrapers to mid-rises, and the rest is a matter of determining whether the economy, location, demand and urbanism come together to make the right climate for a skyscraper.

Kris Fortin, Jeff Jamawat and Victor Negrete are editorial interns at Planetizen. Tim Halbur is Planetizen's managing editor.

Maui's Vacation Rental Debate Turns Ugly

Verbal attacks, misinformation campaigns and fistfights plague a high-stakes debate to convert thousands of vacation rentals into long-term housing.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

In Urban Planning, AI Prompting Could be the New Design Thinking

Creativity has long been key to great urban design. What if we see AI as our new creative partner?

King County Supportive Housing Program Offers Hope for Unhoused Residents

The county is taking a ‘Housing First’ approach that prioritizes getting people into housing, then offering wraparound supportive services.

Researchers Use AI to Get Clearer Picture of US Housing

Analysts are using artificial intelligence to supercharge their research by allowing them to comb through data faster. Though these AI tools can be error prone, they save time and housing researchers are optimistic about the future.

Making Shared Micromobility More Inclusive

Cities and shared mobility system operators can do more to include people with disabilities in planning and operations, per a new report.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

planning NEXT

Appalachian Highlands Housing Partners

Mpact (founded as Rail~Volution)

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

City of Portland

City of Laramie