Freiburg, Germany has become a stunning model of sustainability, thanks in part to Wulf Daseking, the city's Head of Urban Planning since 1984. Sven Eberlein vists Daseking in Freiberg for this interview.

For Professor Wulf Daseking, the City of Freiburg's Head of Urban Planning, longevity and continuity aren't just buzzwords on a whiteboard but themes to live and plan by. After 26 years at the helm of Germany's Environmental Capital, Daseking embodies the notion of sustainability in a city that has seen only four planning directors since World War II.

However, the secret ingredient that earned Freiburg the Academy of Urbanism's European City of the Year Award in 2010 is Daseking's flair for bold and unconventional thinking. From Seepark, a former gravel pit turned recreational eco-park, to Wiehrebahnhof, an old train station cooperatively rebuilt into a thriving cultural arts center, the Professor's fingerprints are all over the projects in the "you can't do that" category.

Daseking and his team have also found creative ways to accommodate population growth within its coveted city limits by using available land to build bustling eco-villages: Rieselfeld, a former brownfield area, and Vauban, once a French military base, are ecologically integrated and socially diverse developments that make car-free and high density living easy, fun, and a matter of civic pride for its residents.

Freiburg has a story to tell, and its recently released Charter for Sustainable Urbanism not only shows its own route to becoming a sustainable city but consists of a series of guiding principles that seek to inspire other cities to follow suit.

On a recent visit to Freiburg, writer and Ecocity Builders contributor Sven Eberlein talked to Professor Daseking about his experiences, visions and the lessons to be learned from the Freiburg experiment by American cities.

Eberlein: In recent years Freiburg gained international attention for its progressive vision of integrating functional and social aspects of sustainability. Was there a point when you decided to become "The Green City"?

Daseking: No, not at all. You have to understand that the history of city planning in Freiburg is based on steadfastness and continuity. We've had only four planning directors since World War II. The first one, Joseph Schlippe, was in charge of rebuilding a city that had been almost completely destroyed. Most people at the time wanted to erase the memories of the past by completely redesigning the city. In fact, almost all the other German cities bought up all the destroyed plots and built a completely new grid, that was the "modern" way of thinking. However, Schlippe recognized that there was value in keeping the old plots and landmarks intact and came up with a planning concept modeled after the original medieval blueprint. He was accused of being much too conservative and ultimately pushed out of his job. Schlippe's accomplishments were finally recognized during the expansion of the pedestrian zone in the 1970s when it became clear how much these public spaces connect and embellish the diverse range of architectural styles.

The other important planner was Klaus Humpert, who was in charge from 1970 to 1982. Humpert brought a new style of building to the city, like Konviktstrasse, which was really run down at the time. It was around the same time when middle class people who had been part of the urban flight after the war were getting tired of mowing their 1000 square meter suburban lawns and looking to move back into the city. So Humpert said we're going to keep the integrity and ease of the old layout but we'll build brandnew buildings in the same style as the old ones. The houses on Konviktstrasse are all virtually new, but nobody knows it. The principal idea is simple, based on hundreds of years of city planning. It wasn't about being green for him as much as it was about adding modern architecture into the existing infrastructure.

And then came Daseking in late 1983, and the first question was: what are we doing here? First came Rieselfeld...

Eberlein: Rieselfeld is widely credited as the first of its kind in terms of building a new development from scratch according to sustainable principles. High density living, zero-energy and affordable homes, car-free streets, access by proximity, cooperative design and ownership, cultural diversity, public transit hubs, all within a 15-minute tram ride from the city center. Was that all your idea?

Daseking: Well, an idea always has many sources. One of the burning issues at the time was that the region was experiencing a lot of population growth and then-Mayor Böhme said they shouldn't all move into the countryside and suburbs. Then Chernobyl happened and the lessons from that were that we should minimize land use to reduce our energy use. With that in mind we introduced thirty initial building proposals that would accommodate the growing population, especially young people and families who wouldn't otherwise be able to afford housing in Freiburg. From those thirty proposals three finalists emerged and the mayor provided the political will to get the green light for the Rieselfeld project.

We wrote up the plan, discussed it with everyone, made lots of tweaks and revisions. We knew three conditions had to be met: First, we wanted to build a real neighborhood, not a park or recreational facility. Second, it had to be compact, everything had to be in close proximity. And third, there had to be easy access to public transit to reduce car use, and most critically, it had to pay for itself without any outside subsidies. We had a design competition, and with few exceptions a lot of remarkable ideas materialized that turned Rieselfeld into an urban district that today attracts attention and visitors from all over the world. And that's without any top notch architectural accents, except for a couple of buildings.

Eberlein: Speaking of attention, the Vauban development has gained even more international notoriety than Rieselfeld for being a living breathing eco-village. How did that come about?

Daseking: Well, after the Cold War ended in 1989 a lot of military bases became obsolete. When the French closed down Vauban there was still a great housing shortage in Freiburg, so Mayor Boehme asked, "what are we going to do here?" At first there were a few big private developers who had petitioned the federal government to buy and build on the land, sparking a big internal discussion in our planning department. We said we're the planning authority here, and since this land is zoned for military use you can't just come in and build a bunch of apartments. You can either build another military base or leave it as open space. The mayer ended up working out a deal with the federal government to delegate authority over land use at Vauban to the city, so that without our approval nothing would happen there.

Then we drew up a plan. We sat together for many months in open discussion. From technical drafters to structural engineers, everyone was welcome to chime in about the future of Vauban. To take up where we left off with Rieselfeld we were drawing up a completely car-free district, which of course didn't quite turn out that way, but we reduced car usage as much as possible. Consider that for every 1000 people in Germany there are 500-550 cars. In Freiburg it's 430 cars, and in Vauban it's below 100. What you have to realize is that you have to create incentives for people to go without car. This may not be possible in every city, but the potential was there in Freiburg.

We approached this within the context of building an entirely new district, a city of short distances, commercial outlets nearby, tram line running right down the middle of it, good shopping centers, public institutions, kindergartens, schools, etc. Another goal was to keep roads small and narrow, keep them primarily as access roads with limited parking time, keep parking garages off site rather than at each building. You can drop off your grandmother or shopping bag in your car but you can't leave your car in the street because the street belongs to the children to play. So this is how we went into the discussion. We said, let's make the city blocks relatively small with high density living, at least for our standards.

Eberlein: For a neighborhood that was conceived and built within such a short time I'm really impressed with how aesthetically pleasing and culturally seasoned Vauban feels. How do you inject culture and character into a neighborhood that is literally built from scratch?

Daseking: Well, you have to mesh together planning principles and existing culture. You have to bring together the different neighbors who are building homes, have them talk to each other and to the architects, so that everyone has a say in what it will look and feel like. If you need to alter the plan a bit, you talk to the people and see if they want to make that change. Think about it, if you go to our medieval old town that took hundreds of years to build, it was the same way, you always had to involve the people who would actually live there.

Let me give you the recent Wiehre Bahnhof (old train station) project as another good example of how to avoid the monotony in style that often comes with building multi-unit housing. Instead of a developer slapping together a cookie cutter building, we wanted all the different stakeholders to be actively engaged in the building process, even initiating it. So we experimented with building cooperatives, which consist of people who agree to build together and then look for an architect, or an architect looks for people with whom he can build. Everyone sits together, and paying close attention to the specific building, plot, residents and usage they custom-design a building that meets everyone's individual tastes and needs. So there's going to be a common entryway and hallways, but each apartment unit ends up being completely unique, made to everyone's own specifications. And of course, along with it all the ecological concerns are covered: Absolute energy efficiency, gray water recycling, children's areas, car access only for drop-offs but no permanent parking spaces. Just some simple basic rules, you just have to implement them.

Eberlein: And you could do this anywhere?

Daseking: Well yes, you could build like this anywhere, but you've got to have a long-term comprehensive approach and plan. I'm just returning from Istanbul, where each month over 50,000 new people move into the city. You can't plan for something like that. They may have a plan in the broadest sense, but there's nothing ecological about it. They just keep building, and every house looks the same. If you try to tell them about our ideas of ecological building design, they'll laugh out loud. And they're right, because to make good on our planning measures and our message that any growth should happen exclusively by increasing density rather than sprawl, that we're going vertical rather than horizontal, takes a lot of work and dedication. You can't just have a couple of people sit together in a meeting and decide that that's what you want to do. It takes a whole long term planning process with everyone on board. And that's how we got the attention of The Academy of Urbanism's European City of the Year competition...

Eberlein: Which is how the Freiburg Charter for Sustainable Urbanism came about...

Daseking: Yes. After we won the competition they asked us to create a template of basic principles that led to our successes. So we sat down and came up with the twelve core principles that have guided us through the process of implementing our plans over the years. The key point is this: The Athens Charter contains principles that it wanted to implement but never materialized. The Leipzig Charter that was written eight or ten years ago similarly stated inherent goals that it wanted to achieve. But what we've got here are fully realized items, and that's what really distinguishes us. What this means is that our tenets and principles have been lived and experienced in the recent past.

Eberlein: Could you imagine working for an American city? Suppose the City of Los Angeles called. How would you apply those principles there?

Daseking: Well yes, of course. I'm actually over there a lot. Our principles are universal, you just have to apply them according to each specific culture and background. In England I'm going to approach it differently than in Germany, and in America it's yet another approach, but you cannot bypass the basic principles. For example, go to England or Northern Ireland and build a church that houses both Catholics and Protestants, with a movable wall for a common space in the middle. You see, that's what we've done here, we've lived it, and here are the examples (points at the charter). We can work together, we can do it. This is my message for the next generation.

But to answer your question, in Los Angeles, you've got what - 4 million people with perhaps as many as 15 million in the metropolitan area? Freiburg has a population of 220,000. So in a city like Freiburg you can have a central government to oversee everything, but why would we presume to do the same in a place like L.A.? Why not have a bunch of smaller autonomous suburbs that can govern and plan for a much more manageable space and population? There may be a few things that need to be centrally directed, but for everything else, like whether a school should be build here or there, each suburb or town should be able to make their own planning decision. This way you get people closer together again. Someone who is miles and miles away from his city hall may as well have no city hall at all. It loses all its meaning and relevance. You see, you could fit 60 or 70 Freiburgs into L.A. or Istanbul and that's how we have to look at it: We have to reconnect people to their civic centers again, and you can only do that on a smaller, more local scale. Big politics doesn't like that idea of a more engaged public, but ask yourself why there's only 50% voter turnout in the US. It's because people feel disenfranchised and powerless, knowing that these distant representative do whatever they want anyway.

Eberlein: Speaking of politics, German city planners generally have more comprehensive control over the planning process due to a more centralized system less dependent on market forces and private profit. How would you implement a long term plan in an American city where there is much less leverage against developers's interests?

Daseking: Here's one thing I would do immediately: Take a city block in Manhattan, with high rises and everything. I would get all the building owners of that block in the same room under the premise of reducing energy use for the entire block by fifty percent and the goal of reinvesting these savings. If I could have the authority to talk to the building owners, that's an assignment I would take on right away. It's really simple. Look, the lights are on night and day, the escalators run 24/7, the windows are poorly insulated, heat is leaking out left and right. You could really do a lot there. Of course, we Germans have to be careful that we don't come across as all-knowing. But what we can do is show what we've done and the principles by which you an do it. Then everyone can adapt it to their own styles and cultural customs. That's why the charter is so powerful, because we've done it and we've lived it.

Eberlein: You have a reputation for being a free thinker, a sort of a renaissance man of city planning. How do you bring creativity into a profession that is often muddled in bureaucracy and extremely averse to new and unconventional ideas?

Daseking: One thing you have to be aware of within a city bureaucracy is that creative minds always play an outsider role. The key in my case was that I've had the support of a great planning team that found a way to realize these visions, against all odds. Just look at the Stühlinger district and the whole axis around the central station that we completely revitalized. Look at the once desolate Seepark area or the industrial parks that now have solar factory buildings. You can really accomplish things with planning. City planning is not just about configuration, it's about ideas and content, about substance. Just like people, it's not only about looks and a facade, but what's behind a person.

The point here is that city administrations usually don't want creative people because they don't fit into the system. So when a creative person like myself is thrown into a system like that you're always struggling rather than functioning. The key is to find the right openings and slip through them. One of the mayors once said to me that I wasn't maneuverable. What does that mean? Maneuverable for whom and towards what? When you're in the presence of administrators you'll notice a clear and authentic difference between creative people and bureaucrats. The creative person is very conscious of what he's done, whether it was good or bad, and whether the final outcome works, whereas the administrator's primary concern is whether it was done by the book. The administrator might even say, "well I did everything by the book, so I don't care what the final creation looks like."

Ultimately though you can see with your own eyes what you've built and whether it works. We planners can see it, whereas a doctor has to go to the cemetery. Often the administrator wonders why the planner is doing it a certain way, going off script, perhaps even thinking that I'm on some sort of a power trip. But I'm not on a power trip at all, I just want to see a great functioning city. That's what I was trained for, and that's why the city hired me. After all, they wanted a city planner and not a subcontractor who rubber stamps every project.

Eberlein: What are the core issues that need to be addressed by the city of the future?

Daseking: First, we have to redesign our inner cities with ecological principles in mind. Another pivotal issue will be to keep working towards social justice and economic parity. Fostering cultural diversity will be very important. And of course, education, you have to have an educated population for any of this to happen. Obviously, all these issues are interconnected, a diverse and educated populace with economic opportunity is the foundation of an ecologically balanced city. There's a lot of work ahead for generations to come, and I'm excited about it.

Sven Eberlein is a writer living in San Francisco, with roots in Germany. His work has appeared in YES! Magazine, Global Rhythm, Elephant Journal and the San Francisco Chronicle, among others.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Restaurant Patios Were a Pandemic Win — Why Were They so Hard to Keep?

Social distancing requirements and changes in travel patterns prompted cities to pilot new uses for street and sidewalk space. Then it got complicated.

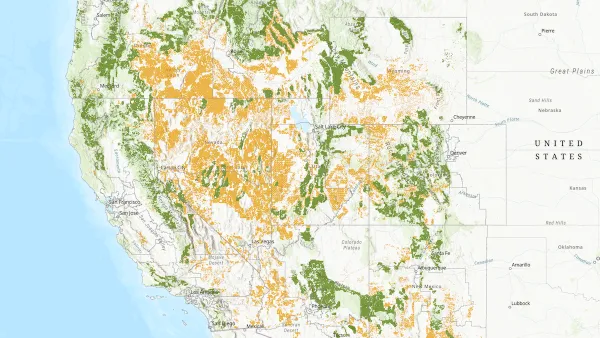

Map: Where Senate Republicans Want to Sell Your Public Lands

For public land advocates, the Senate Republicans’ proposal to sell millions of acres of public land in the West is “the biggest fight of their careers.”

Maui's Vacation Rental Debate Turns Ugly

Verbal attacks, misinformation campaigns and fistfights plague a high-stakes debate to convert thousands of vacation rentals into long-term housing.

San Francisco Suspends Traffic Calming Amidst Record Deaths

Citing “a challenging fiscal landscape,” the city will cease the program on the heels of 42 traffic deaths, including 24 pedestrians.

California Homeless Arrests, Citations Spike After Ruling

An investigation reveals that anti-homeless actions increased up to 500% after Grants Pass v. Johnson — even in cities claiming no policy change.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Heyer Gruel & Associates PA

JM Goldson LLC

Custer County Colorado

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

Transportation Research & Education Center (TREC) at Portland State University

Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Claremont

Municipality of Princeton (NJ)