Unsightly and space-consuming, parking is nonetheless a key component for most urban development. But the rise in innovative parking solutions and mechanization technologies is poised to transform the parking garage from an eyesore into a cohesive element in any sustainable, walkable and livable project.

The parking garage is a frequently contentious and often maligned building type, but it is also a very important building type that offers many solutions to address today's numerous complex issues of architecture, sustainability, transportation and planning. With the development patterns in the United States spanning from the density of New York City to the sparse rural countryside and everything in-between, providing Americans with choices concerning transportation and lifestyle is crucial. Parking is always a part of this mix and studying the evolution of the typology offers many insights. As the issues of long-term sustainability of communities are coming to the fore in discussions of financial viability and environmental concerns, the parking garage can provide the links and connections necessary by allowing the development of walkable communities within a networked transportation system, creating greater sustainability.

The parking garage is a frequently contentious and often maligned building type, but it is also a very important building type that offers many solutions to address today's numerous complex issues of architecture, sustainability, transportation and planning. With the development patterns in the United States spanning from the density of New York City to the sparse rural countryside and everything in-between, providing Americans with choices concerning transportation and lifestyle is crucial. Parking is always a part of this mix and studying the evolution of the typology offers many insights. As the issues of long-term sustainability of communities are coming to the fore in discussions of financial viability and environmental concerns, the parking garage can provide the links and connections necessary by allowing the development of walkable communities within a networked transportation system, creating greater sustainability.

The parking garage frequently acts as the connection for disparate planning environments. Currently we are seeing the parking garage connecting bicycles, advanced transit such as Personal Rapid Transit, and alternative vehicles such as electric and fuel cell vehicles. Many solutions exist and they are specific to each site and location as providing parking spaces is still an integral part of the design and planning process. In studying and documenting the evolution of this building type, these "new" solutions -- while they may appear currently innovative -- have been seen at different times throughout the 20th century. Often the parking garage actually led the way in the sustainable and innovative solutions that have found their way into our everyday built world.

The Evolution of Mechanized Parking

In the 20th-century American city, speed became the prerequisite for the success of any endeavor, and parking garage designers were compelled to be responsive to that demand. Mechanization is one of the results. Though they may be thought of as a futuristic solution that has only recently begun implementation, mechanized garages were designed and constructed in the United States during the 1920s, the 1950s and the 1960s. Mechanized garages eventually became one of the leading parking solutions in Asia and Europe and are poised to be among the important solutions for the 21st-century United States.

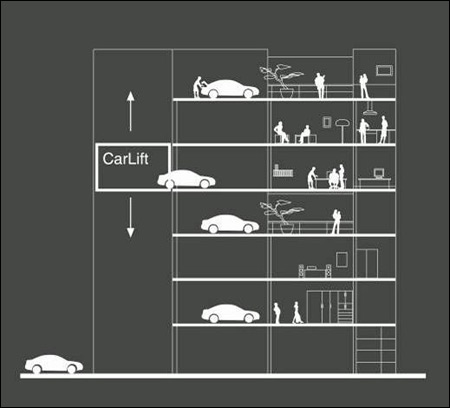

Mechanization in parking garages has evolved over the decades into a modern vision of computer-controlled parking facilities. Today's computerized parking offers a number of advantages over the traditional ramp garage. First and foremost, it can reduce the space allocated to parking by at least 40 percent-in part because it does not require driving ramps or walkways for pedestrians, and in part because the floor-to-ceiling heights need to accommodate automobiles only. What modern approaches to mechanization have in common with the systems of the past is the advantage of safely and efficiently parking a large number of cars in a small area. Thanks to new software, throughput-the number of cars flowing in a single direction that a system can handle in a specified time period-has increased greatly, and garage designers can now accurately assess how a facility will manage peak traffic volumes. Because of suburban development patterns, land constraints in the United States have not been serious enough to spur significant construction of mechanized facilities (with the exception of car stackers) since the 1960s; however, growing resistance to sprawl, densifying suburbs, issues of historic preservation and the return to central cities will certainly lead designers to take a fresh look at mechanized solutions.

By rethinking and modernizing our parking facilities, it could be possible for a driver to call a mechanized facility in advance so that the automobile will be ready by the time the driver arrives. Such arrangements would be particularly useful in dense urban environments, and at car rental agencies at large land-impacted metropolitan airports. Integrating mechanized facilities into the master plan for a dense area would create opportunities for better land use, especially if the facilities were linked to other transportation systems and included an advance-notice system for retrieval. Computerized facilities will thus become increasingly important in dense urban areas, or where the use of additional land for parking is impossible or undesirable. Reducing the amount of space required for parking adds more leasable space to a development, creating additional real estate opportunities. Because the facades of computerized facilities can more readily complement those of surrounding buildings, they can more easily blend in with existing architectural patterns or they can be highlighted as amazing feats of modern engineering. Computerization also simplifies the building engineering, allowing a simple frame structure that is perfect for adaptive re-use as movement patterns change and can alter fire and ventilation code issues in a positive way. It also permits accelerated depreciation and may qualify a facility for municipal financing.

Combining Automated Parking With Other Land Uses and Building Types

Because computerized parking is safe and secure for both the car and its owner, these facilities are more valuable as amenities. Dents and scratches are no longer a concern: once the driver leaves the automobile, it will not be driven again until it is retrieved; moreover, throughout the time that the vehicle is in the facility, it will not come into contact with other cars or with the parts of the system itself. Because neither drivers nor passengers enter the facility, computerized garages do not have to grapple with the issue of pedestrian safety. Finally, computerized systems can be flexibly combined with other land uses and building types. For example, underground computerized systems require very little aboveground surface area, and create opportunities for small, park-like pavilions above for entry.

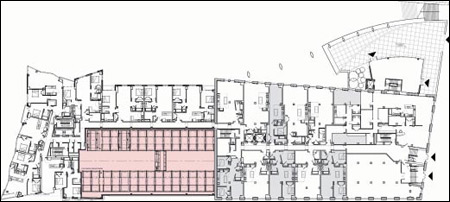

In many cities, older buildings with large floor plates, such as warehouses, are often in need of revitalization. Because mechanized parking systems are virtually emissions-free, they can be safely placed in the central core of such buildings-where there is the least natural light-making good practical use of otherwise undesirable space. Similarly, because mechanized parking systems have such a small footprint, they can be located on urban "notch lots"-the small, undeveloped spaces, surrounded by existing buildings, that are often found in older urban centers. The additional parking created through the use of notch lots may be sufficient to make otherwise infeasible commercial projects viable.

Integrating the Parking Facility

As density increases in existing downtowns and edge cities, integrating the automobile-and, therefore, the parking facility-remains a tremendous challenge. The integrative approach in which the parking facility is conceived as a public building and as public space, therefore as an amenity opens up a wealth of options. The lobby of a computerized facility can be designed as a community gathering space, where drivers and passengers wait for their cars to be retrieved. Thoughtful planning can render such spaces integral to the community: the lobby might incorporate a coffee shop, a newsstand, a post office, a dry-cleaner, day care, retail shops, and other similar amenities; an automatic car wash would be another natural addition. Here, time would slow down, and the clock would be turned back. What was the norm well into the 1950s-waiting in a beautiful (and now air-conditioned) lobby while your car was being retrieved, sipping a cup of coffee, and talking with neighbors or catching up on the latest news-could return as a vibrant, vital part of community life.

As it becomes increasingly clear that the "speed" of the self-park garage is more a matter of perception than reality, a mechanized approach begins to look just as efficient and reliable, if designed properly. By building on the excellent infrastructure that already exists in many urban areas, it is possible to achieve the best of both worlds: dense, pedestrian-friendly environments that also accommodate the automobile, and that support and encourage what is best in urban life.

Some Current Examples

Recently, several older mechanized parking systems have been modernized, including the New World Tower, a 12-floor Bowser facility in Miami. Thanks to new elevators and a computerized inventory-management system, the facility reduced labor costs and customer waiting times, increased its throughput by 40 percent, and saved $351,279 over a five-year period.

The 324-car, fully computerized Hoboken facility, constructed in 1999, is a public garage designed by Gerhard Haag, of Robotic Parking. Cars are transported and stored on individual pallets, and the three directions of internal movement-along the aisles, in and out of storage bays, and from one level to another-are controlled separately. Because 18 different mechanical movements can occur simultaneously, the system can theoretically handle many cars at once.

The Grand Parc, a 74-space, four-level private parking facility constructed in 1999 under an apartment building in Washington, D.C., uses a stacker crane system manufactured by Wohr-Stopa in Germany, and distributed in the United States by SpaceSaver Parking Systems. In this system, the driver enters a compartment where the car stops and rests on a pallet. The driver then leaves the area and activates the system by means of an electronic card reader located outside the compartment. The stacker crane-a vertical tower that moves vertically and horizontally at the same time-moves the car (which is still on its pallet) into a parking slot, which may be on either side of the tower. A turntable within the transfer compartment is used to face the car in the proper direction for exiting.

New York City's first fully computerized automated facility opened in the spring of 2007, within a luxury condominium project located at 123 Baxter Street. The project is the work of AutoMotion Parking Systems, an American subsidiary of Stolzer Parkhaus, of Strassburg, Germany. AutoMotion is working on another project in New York City.

A number of computerized, fully automated facilities are currently being discussed or planned. One such project is the Buildings at Lovejoy Wharf, in Boston, a project designed by the Architectural Team. Another example is a new system to be located at 1706 Rittenhouse Square, in Philadelphia's Center City district, as part of a proposed 31-story condominium development. Because the lot is too small for traditional underground parking, the best solution is a mechanized facility. The fully automated system will have a throughput of one car per minute and will accommodate 64 vehicles underground, on a steel racking system connected to a conveyor belt. In this project, the Parkway Corporation, working with the Scannapieco Development Corporation, is using the Multiparker System, manufactured by Wohr of Germany. Other examples are 7 State Circle, in Annapolis, Maryland; 310 Webster Avenue, in Cambridge, Massachusetts; and One York, in New York City.

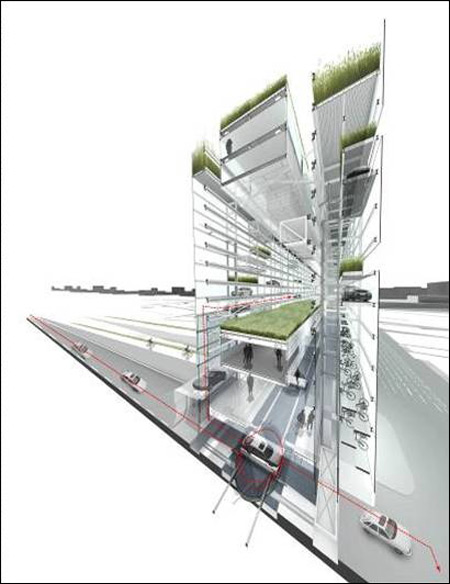

A 2003 competition-the Stop Go, Chicago Portal Project-asked designers to create a 1,000-car garage between Madison and Monroe, spanning the expressway. Most of the proposals focused on hiding the garage with landscaping or using other amenities to distract from it. One of the first-place winners, however, celebrated the garage: the design, entitled Filter Garden, consisted of two 130-foot- (40-meter-) tall automated parking towers separated by a "filtering garden" for bicycles and pedestrians. The towers would serve as visual gateways to the city, and would also provide clues, for the speeding cars below, as to the location of parking.

A similar vision was realized in Copenhagen, through a 50/50 partnership between the city government and a housing development company. Each automated parking tower houses 700 vehicles and offers users a wonderful interior waiting area. The activated space between the towers features a public garden and a skate park. And at a recent condominium project in New York, designed by Annabelle Selldorf, vertical elevators for cars will allow residents to have private garages up in the sky, next to their homes. The successful provision of parking is not merely a question of where, what type, and how much, but of imagination, innovation, and appropriate focus on the architectural challenges and opportunities posed by the building typology.

Shannon Sanders McDonald is a practicing architect licensed in Georgia and Illinois, as well as an author and frequent speaker on architecture, parking, environmental, transportation, and related issues. Ms. McDonald has written numerous articles on various aspects of parking and movement, and has given presentations at the meetings of a number of organizations, including the Advanced Transit Association, the American Institute of Architects, the American Society of Civil Engineers (receiving a speakers award), the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture, the Construction Specifications Institute, the International Parking Association, the National Transportation Research Board, and the Vernacular Architecture Forum. She has taught architecture at many levels across the country.

McDonald is the author of the new book, The Parking Garage: Design and Evolution of a Modern Urban Form, 2007, available from the Urban Land Institute. Some of this article is excerpted from the conclusion of Chapter 5: Mechanization: A Taste for Technology, which focuses on mechanized and automated parking.

Study: Maui’s Plan to Convert Vacation Rentals to Long-Term Housing Could Cause Nearly $1 Billion Economic Loss

The plan would reduce visitor accommodation by 25,% resulting in 1,900 jobs lost.

North Texas Transit Leaders Tout Benefits of TOD for Growing Region

At a summit focused on transit-oriented development, policymakers discussed how North Texas’ expanded light rail system can serve as a tool for economic growth.

Using Old Oil and Gas Wells for Green Energy Storage

Penn State researchers have found that repurposing abandoned oil and gas wells for geothermal-assisted compressed-air energy storage can boost efficiency, reduce environmental risks, and support clean energy and job transitions.

Santa Barbara Could Build Housing on County Land

County supervisors moved forward a proposal to build workforce housing on two county-owned parcels.

San Mateo Formally Opposes Freeway Project

The city council will send a letter to Caltrans urging the agency to reconsider a plan to expand the 101 through the city of San Mateo.

A Bronx Community Fights to Have its Voice Heard

After organizing and giving input for decades, the community around the Kingsbridge Armory might actually see it redeveloped — and they want to continue to have a say in how it goes.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Ascent Environmental

Borough of Carlisle

Caltrans

Institute for Housing and Urban Development Studies (IHS)

City of Grandview

Harvard GSD Executive Education

Toledo-Lucas County Plan Commissions

Salt Lake City

NYU Wagner Graduate School of Public Service